Timeline: U.S.-Mexico Water Treaty and Disputes

The two countries have reached a compromise in dispute over a 1944 treaty, but the amount of water Mexico can release in 2025 remains unclear

Research assistance by Kathleen McCook

The Rio Grande River received a lot of attention during the border crises. Migrants frequently entered the country illegally by crossing the river along the U.S.-Mexico border in Texas. Governor Greg Abbott had a floating border installed on the river, which Mexico argued violated a 1944 water treaty between the two countries.

The U.S. contends that Mexico was already violating that treaty, but for a different reason. Mexico is supposed to send 1.75 million acre-feet of water (1 acre-foot is nearly 326,000 gallons) to the U.S. every five years from the Rio Grande and six tributaries. In return, the U.S. gives Mexico 1.5 million acre-feet each year from the Colorado River.

But Mexico is way behind schedule. By late April, it had only released about 531,000 acre-feet during the current five-year cycle, which ends in October. After some political hardball by the Trump administration — which included rejecting Mexico’s request for a Colorado River water transfer — the two countries agreed to a compromise on April 28: Mexico will send up to 420,000 acre-feet by October, depending on hydrology conditions. U.S. and Mexican officials will meet in July to assess those conditions, according to a State Department fact sheet.

Even if Mexico manages to release that much water, it will still be well short of delivering 1.75 million acre-feet. To address that, Mexico agreed to an immediate release of 56,750 acre-feet from the Amistad Reservoir — which is managed by both countries — and monthly releases from Amistad and another reservoir. It also agreed to let the U.S. get 50% of the water from the six Mexican tributaries, an increase from the one-third called for in the 1944 treaty.

The deal is related to another agreement, Minute No. 331, approved in November by the International Boundary Water Commission that allows for new strategies, says Rosario Sanchez, a senior research scientist at Texas A&M’s Water Resources Institute.

“The problem is it is based on the assumption that there is enough water for everyone. There’s not,” Sanchez says.

Here are 2025 water levels at Amistad Reservoir compared to the previous two years.

Not good — and this is one of the reservoirs that’s supposed to have monthly releases under the compromise deal.

Mexico rejects accusations that it’s been violating the water treaty. It blames drought conditions, and the treaty does allow either country to withhold water during times of “extraordinary drought.” The problem, says Sanchez, is the treaty doesn’t define what qualifies as an extraordinary drought.

“My recommendation is to try to define what extraordinary drought is because it’s not extraordinary anymore,” Sanchez says.

Here’s a timeline of some key moments since the treaty was signed, including the escalating tensions leading up to the April 28 compromise agreement:

Feb. 3, 1944

The United States and Mexico sign a treaty relating to the “utilization of waters of the Colorado and Tijuana Rivers and of the Rio Grande.” It takes effect Nov. 8, 1945.

Aug. 30, 1973

The U.S. and Mexico agree to Minute 242, which sets salinity standards for the Colorado River. Agricultural runoff increased salinity levels so high that the water destroyed crops in Mexico.

February 4, 2020

Hundreds of Mexican farmers occupy the La Boquilla Dam in Chihuahua in protest of the Mexican government’s plans to transfer water to the U.S. They argue that their water needs should come first, especially with the dam below capacity. Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador criticizes the farmers for being too demanding, and the protesters are removed by National Guardsmen the following day.

September 9, 2020

Protesters return to the La Boquilla Dam, closing its sluice gates and hurling Molotov cocktails and other projectiles at Mexican National Guardsmen. Three people are arrested. Civilians attack National Guard vehicles that were transporting the arrestees. A firefight ensues, and two people die.

October 21, 2020

The International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC) agrees to Minute No. 325. Mexico says it will provide the U.S. with water from the Amistad and Falcon International Reservoirs to prevent a second consecutive water cycle shortfall just days before the October 24 deadline. The U.S. agrees to temporarily assist Mexico if the transfer from the two reservoirs makes it difficult for Mexican communities downstream of the Amistad Dam to meet their water needs.

November 7, 2024

The IBCW agrees to Minute No. 331 to give Mexico more flexibility to meet water deliveries. It also establishes the binational Rio Grande Projects Work Group and the Rio Grande Environment Work Group.

March 20, 2025

The State Department’s Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs denies Mexico's request for a special Colorado River water delivery to Tijuana. The Bureau announces on X that it’s the first time the U.S. has rejected a non-treaty request for Colorado River water.

Newsweek reports that about 90% of Tijuana’s water comes from the Colorado River. The decision is praised by U.S. Senator Ted Cruz of Texas.

Stephen Mumme, a Colorado State professor who specializes in water policy, tells Newsweek that the decision breaks two norms:

Avoiding any connection between the Colorado River and the Rio Grande.

Not restricting urban water supplies, which take priority during water shortages.

Sanchez of Texas A&M tells Racket the move was effective in the short term, but she worries about long-term consequences.

“I don’t like the precedent that it created, because now Mexico can do that, too.”

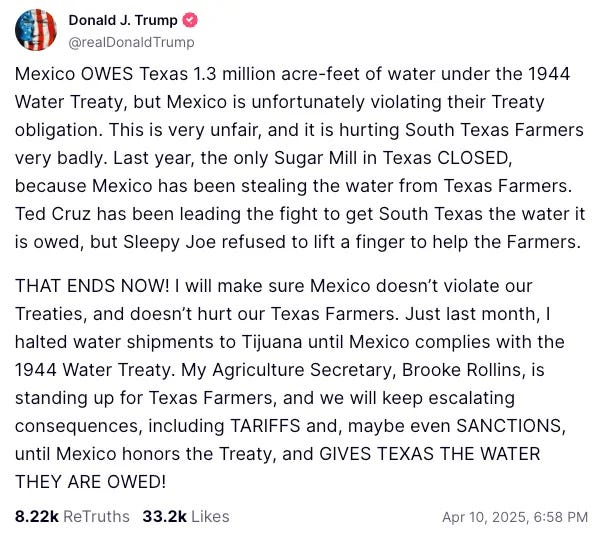

April 10, 2025

President Trump says Mexico is “stealing the water from Texas farmers.”

April 28, 2025

Mexico agrees to release up to 420,000 acre-feet of water over the next six months and increase the U.S. share of water from six Rio Grande tributaries.

May 5, 2025

The U.S. reverses course and agrees to Mexico’s request to release water from the Colorado River.

Sounds like both countries need to work on desalination. I don't see another viable solution.

Instead of $400 billion to Ukriane, the US government could have funded several desalinization plants along the West coast, thus reducing water use in California that could be directed to other southern border states.

Fresh water isn't a supply challenge; it is a logistics issue and storage challenge. These are challenges that we already have solutions for, but for the idiot technocrats in charge that cannot get anything done.