Time to Pump the Brakes on Artificial Intelligence Finance?

Big Tech needs trillions to fund their AI dream, much of it from insurance companies and pension funds. What could possibly go wrong?

Artificial Intelligence dealmaking has surged in 2025 and looks to keep right on going in 2026 on the way to the stupidity where all booms eventually end up.

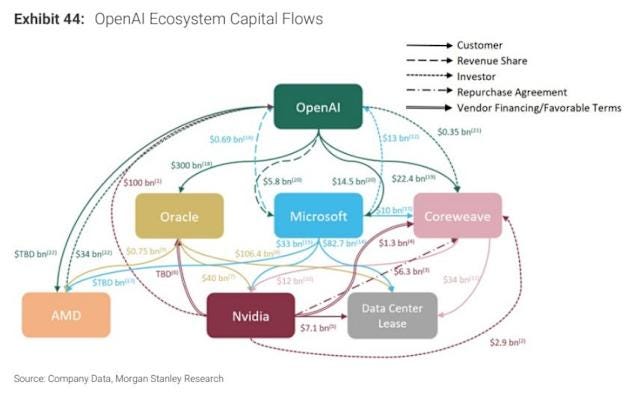

Deals among the major players have reached around $1 trillion. Nearly every week, tech giants like Oracle, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, Google and Nvidia announce multi-billion dollar circular investment deals with AI, large language models, or “chatbot” creators such as OpenAI, Anthropic, and xAI, along with data center providers like Coreweave and several smaller firms. These are circular investments where the tech giants pour billions into AI chatbot companies, which rely on massive data centers and purchase or lease millions of graphic processing units (GPUs), the chips used for AI computing.

Amazingly, the deals closed in 2025 may be just the tip of the iceberg. A recent study by McKinsey & Co. concluded that data centers will require $6.7 trillion worldwide to keep pace with demand for computing power.

What could go wrong?

Concerns for hyperscaler stock investors

Hyperscalers provide large cloud-based computing services, the largest being Microsoft, Oracle, Meta, Amazon and Google. Institutional investors, including pension funds and insurance company portfolios, own large amounts of hyperscaler stocks. The tremendous and historic capital expenditures (“CapEx”) by hyperscalers could significantly weaken the financial position of companies that make up 26.1% of the S&P 500 as of November 26th. The spend now and expect revenues to catch up in 3 to 5 years plan is a perilous and perhaps fanciful proposition. Revenue is dependent on the success of the leading chatbot developers, the biggest being OpenAI. Fortune Magazine recently reported that investment bank HSBC doesn’t expect OpenAI to deliver profits that soon

HSBC Global Investment Research projects that OpenAI still won’t be profitable by 2030, even though its consumer base will grow by that point to comprise some 44% of the world’s adult population (up from 10% in 2025). Beyond that, it will need at least another $207 billion of compute to keep up with its growth plans. This stark assessment reflects soaring infrastructure costs, heightened competition, and an AI market that is surging in demand and cash-intensive to a degree beyond any technology trend in history.

Additionally, the AI ecosystem of hyperscalers, chatbot creators and AI chip makers is incredibly integrated.

This inter-connectivity could lead to a systemic meltdown as the problem of one major player could become a problem for all the players. Normally, I might say let the buyer beware, but considering the concentration of risk in companies that make up more than a quarter of the S&P 500’s market capitalization, anyone who owns stocks and mutual funds —including retirement accounts and insurance company portfolios — could lose substantially.

Private credit, including insurance and pension assets, will fund a good portion of these risky investments

Hyperscalers and other AI players will have to borrow billions each to fund all the necessary AI infrastructure. A recent article from the F.T. noted that hyperscalers are burning through cash, with Oracle leading the way down.

Of the five hyperscalers — which include Amazon, Google, Microsoft and Meta — Oracle is the only one with negative free cash flow. Its debt-to-equity ratio has surged to 500 per cent, far higher than Amazon’s 50 per cent and Microsoft’s 30 per cent, according to JPMorgan. While all five companies have seen their cash-to-assets ratios decline significantly in recent years amid a boom in spending, Oracle’s is by far the lowest, JPMorgan found.

In the old days of a few years ago, these hyperscalers — which Bloomberg reports have a combined $324 billion in outstanding corporate bond debt — would do a combination of investing their cash and borrowing in the corporate bond market. That’s no longer a complete option for this amount of funding, not even close. To achieve the level of spending the hyperscalers need, if they tried to raise all the funds in the public bond market, they would probably all be downgraded to junk by the ratings agencies, not to mention increasing interest rates for all of us (like mortgage rates).

To the delight of Wall Street, much of the needed funding will come from “Off Balance Sheet” sources, a lot of which come from private credit. As we have already reported, private equity firms have been snapping up life insurance companies and annuity providers, and funneling these companies’ assets into their private credit deals.

A good example is the recent Meta “Beignet” deal. Meta is constructing a massive data center in Louisiana in a deal that the Wall Street Journal labeled a“Frankenstein financing.” The $30 billion deal, structured by Morgan Stanley and the private investment firm Blue Owl, combines private equity and semi-public bonds, all of which will be done off Meta’s balance sheet. The owner of the data center will be the Special Purpose Vehicle, Beignet.

In the deal, Blue Owl invests $3 billion for an 80% equity stake, while Meta ends up with 20% of the equity for funds it has already invested in the project. Once the data center is built, Meta will be the sole tenant. The remaining $27 billion of funding will come in the form of debt, which will be investment-grade-rated notes. Investment manager giant PIMCO will own $18 billion of the notes, while private credit firms will most likely purchase the rest. Principal and interest for the notes will come from Meta’s lease payments to Beignet. The notes mature in 2049. Interestingly, Meta has the right to walk away every four years. If Meta exercises this option, Blue Owl will sell the data center and if there is a loss, Meta is obligated to make up the difference.

As noted earlier, all else equal, Meta will be burning through its substantial $44.5 billion cash pile as it ramps up its AI capital expenditures (“CapEx”). With current expenditures on AI far exceeding revenues, what does that mean for Meta’s future financial condition?

Future value of data centers

It’s a boom time for data centers as demand exceeds supply. Valuations of data centers and expected lease payments are probably at their most favorable point right now. Generally, boom times bring overbuilding and a glut of whatever is being built. What if in five years or ten years, lease agreements and data center valuations drop sharply? What if data centers go unused or dark? As McKinsey and Co. asked in its article, “Will demand for data centers rise amid a continued surge in AI usage, or will it fall as technological advances make AI less compute-heavy?”

Beignet is in the middle of nowhere, Louisiana. Many of the data centers being constructed are also in the middle of nowhere. If they go dark on AI computing what else could they be used for? At least when other commercial real estate sectors go bad, like shopping malls, there is some recovery value, as at least something else can be built there. Data centers in the middle of nowhere are useless without AI.

In addition, there’s a growing pushback against data centers near populated areas with their demand for power and water, as well as noise concerns. Microsoft recently issued a warning to investors about community opposition, which could put more data centers further out into the boondocks, leaving them almost worthless should they go dark.

Another deal that was recently completed is Elon Musk’s xAI circular deal with Nvidia. xAI is constructing a massive Tennessee data center, Colossus. A special purpose vehicle will purchase GPUs from Nvidia and then xAI will lease-to-own approximately 300,000 GPUs for five years. The total size of the deal will be approximately $20 billion — $7.5 billion of equity and $12.5 billion of notes. Nvidia will contribute $2 billion in equity, while private credit giant Apollo is arranging the debt financing. The lease payments will go toward partially paying down the notes. The big question here is, what are these chips going to be worth five years from now?

In five years, there may be better chips, there may be too many chips, there may be cheaper chips, or maybe a combination of all three. There could be a big shortfall between what note holders are owed and the residual value of the chips.

Asset-Backed Securities

ABS is a source of funding for AI infrastructure. Wall Street has already begun packaging data center and GPU leases into ABS, creating approximately $11 billion in 2025.

Similar to ABS on commercial real estate (CMBS), lease payments on data centers are being packaged up, divided into tranches and rated. Since the leases are long-dated, they will fit perfectly into insurance and pension fund needs. Expect insurance and pension funds to buy such ABS, probably in the highest credit rating tranches.

Similar to Collateralized Loan Obligations, as we reported this past July, insurance companies and pension funds owned or managed by private equity will invest heavily, more than those not owned by private equity. The worry I have here is that we are dealing with a very new product (data centers and GPU leases) with very little historical data and a lot of uncertainty. How will rating agencies such as S&P and Moody’s arrive at their ratings?

These investments, either in the form of private credit investment or ABS investment, could be fine for those who voluntarily take the risk. If an investor wants to invest in a private credit deal that specializes in AI infrastructure, they should have at it. This is what private credit should be all about. However, if it is your pension or your annuity or your insurance policy, you don’t get a vote on whether or not you want to take this risk. You likely won’t even know you have this risk until something bad happens, that is.

Eric Salzman and his guests also discuss the rampant pace of AI deals on his personal Monkey Business podcast.

As with all of these financial manias, the goal is to get the big pension funds to come on board so that you are "too big to fail" (i.e., you can pressure the government for a bail out when it all comes crashing down). The people leading the charge are well aware of 2001, 2008, 2020 --- they know the game: privatise the profits and socialise the losses.

Is AI advanced enough that we can ask it if this is all a good idea?

“Beignet” is a perfect name: yummy but no nutritional value and you’re starving again in 10 minutes!!