Interview: FIRE Counsel Tyler Coward on Deportations, Title VI, Mahmoud Khalil

There's a lot of noise around this story, but real problems as well

Is it infuriating to see people who kept mum during years of assaults on the First Amendment suddenly acting broken up about its future? Of course. But that doesn’t mean they’re all wrong. There are serious concerns about the new administration. I spoke with Tyler Coward, lead government counsel for the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, or FIRE, the group that did such incredible work defending civil liberties during the digital censorship era:

Matt Taibbi: Let’s start with the broader issues and work our way toward [Palestinian activist] Mahmoud Khalil. Could you walk me through some of the recent speech controversies involving the Trump administration?

Tyler Coward: First, student political protests at institutions have been around for almost as long as institutions have existed. I was just on a panel this past weekend at the Stetson University Higher Education Law and Policy Conference, and a professor who does education law and the history of education law talked about protests, dating back to the Whiskey Rebellion era. Then obviously, even before the 60s, we had a big protest movement in the 30s. There’s a lot of overlap between workers’ rights protests, and organization and labor organizations in the UK and the strikes there, and progressive and labor-type movements on campus in the U.S.

When I started at FIRE 10 years ago, there were campus protests centered around invited speakers. A lot of invited speakers were protested and shouted down at institutions. They tended to be right of center.

MT: [Milo Yiannopoulos] and so on.

Tyler Coward: From Milo to Ben Shapiro and Anne Coulter, even Richard Spencer. That was my first few years of FIRE. Now we’re smack in the middle of a new round. This has been an issue on campus for a long time. The newest round of protests around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict enjoy a long tradition of being protected both by university policies and by the First Amendment. Universities do have what’s called “Time, place, and manner” authority to regulate speech on campus. Time, place, and manner restrictions on a public college campus that is bound by the First Amendment need to be reasonable. They need to be tailored to serve a significant institutional interest, and they need to be content and viewpoint neutral, and leave open alternative channels for communication.

A quintessential example of a reasonable university policy to satisfy time, place, and manner is [limiting the use of] amplified sound outside of a dorm at one o’clock in the morning. Such a restriction would satisfy a reasonable interest of the institution to ensure that students have a place to sleep without being woken up by the use of amplified sound, at a time,—1 a.m.—and place, right outside the dorm. That’s sort of the quintessential permissible restriction on speech in these open outdoor areas of campus.

When government starts getting into a little bit of trouble, and a lot of FIRE litigation has borne this out over the years, is when these restrictions are not reasonable. They might restrict speech to very small areas of the campus community. These are often referred to as “free speech zones.” FIRE has engaged in a lot of litigation over the years over these overly restrictive free speech zones, and courts across the country have resoundingly found in favor of FIRE’s plaintiffs over these university policies.

MT: Could you give us an example?

Tyler Coward: With a lot of these, we don’t actually get opinions, because university general counsels—once they realize, oh dang, this policy slipped out and I didn’t notice it, they generally settle. There are two where we did get written opinions. One was a case called Roberts v. Harrigan back in 2004 at Texas Tech University. Texas Tech had a free speech gazebo. It was a small 15-by-15-foot gazebo. That was the only place where students could demonstrate. You can imagine the logistical problems with a pro-life and a pro-choice protest happening simultaneously. And we got a great opinion from the judge saying that parks and sidewalks in green spaces are presumptively available to free speech activity. And that sort of means that, for the notion that if you’re the government, the burden is on you to justify why a restriction is permissible and not on the person speaking to justify why they should be there.

So anyway, that’s sort of a history of the use of these time, place, and manner authorities. When they’re unreasonable is when they restrict speech to small areas, and when they veer into content and viewpoint restrictions.

MT: Which brings us to the present issues.

Tyler Coward: Right. Transitioning into the campus protests we have today, a lot of these protests have been peaceful and have been centered around constitutionally protected speech and expression. A lot of them haven’t, or have veered into violence, or toward intimidation, true threats, or actual discriminatory harassment as defined by the United States Supreme Court. And when an institution knows that these sorts of targeted actions are against an individual based on their protected status — and Title VI protects against discrimination based on national origin, shared ethnicity, and race — and the institution fails to take steps to remedy those actions, then they can be found in violation of Title VI.

And that’s sort of where we are right now. The remedy for violating Title VI is the revocation of federal funding. The government says if we’re going to give you federal dollars, you cannot engage in discrimination based on these protective characteristics while receiving our money. In almost every educational institution in the country — 95-plus-percent majority of higher ed institutions — receive federal dollars either through grant contracts or federally subsidized student loans.

MT: Outlining what the Trump administration can do: it can announce, “We’re going to enforce Title VI”? Are they going beyond that?

Tyler Coward: I think during the Biden administration, I don’t know what their final number was, but they were upwards of close to a hundred open investigations against institutions for violating Title VI. The tricky thing is that religion is not a protected class in Title VI and higher education. So federal interpretation of Title VI dating back to the George W. Bush administration says that while religion is not protected, not all discrimination faced by Jewish students, by Muslim students, by Sikhs, is directed at them based on actual religious practices, which we could not protect against. Sometimes it’s based on cultural things, including cultural attire or garb or cultural observances. When it’s tied to that sort of shared culture, from a particular region or country, then some of this discrimination can be subject to Title VI protections, not based on actual religious practices, but more about cultural heritage and shared heritage.

So I think that the practical effect of this is that 95% of the harassment or discriminatory harassment faced by Jewish students or Muslim students isn’t based on their actual religion. It is based on some sort of other stereotype associated with a particular country or region. And that’s how Title VI can protect students.

MT: Including their political views?

Tyler Coward: Well, that’s up for debate. FIRE doesn’t take a position on whether or not particular protected classes should or should not exist, but we actively include political affiliation or political thought in the protected class status because politics should be robustly debated. And there are ongoing debates about whether or not Zionism is a stand-in for anti-US hatred or a political ideology that should be separate or separated from Title VI-related issues based on ethnicity or national origin, things like that. And FIRE has not fully weighed in on whether or not anti-Zionism is antisemitism, but what we have said is that definitions of antisemitism that include criticisms of Israel as a basis to find that speech antisemitic and subject to sanction are overbroad, and frankly, are the definition of viewpoint discrimination that comes from the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition of antisemitism. And are you familiar with that, Matt?

MT: Yes. I remember it came up with Trump’s 2019 Executive Order on Combating Anti-Semitism.

Tyler Coward: Things like calling the state of Israel a “racist endeavor.” People can call the United States a “racist endeavor.” In fact, many people do. And you can call a lot of countries across the world racist endeavors. If there’s one country where you can’t say that, that is classic viewpoint discrimination, applying double standards by requiring of Israel a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation. What does that mean in practice? If we’re allowed in America to focus on issues that are particularly important to us, then we are applying double standards by requiring of Israel what is not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation. How is an institution supposed to determine whether or not my advocacy is a double standard? Am I supposed to criticize other countries a little bit too, to make clear that I’m not applying a double standard?

MT: Seems like a problem.

Tyler Coward: Another is drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policies to that of the Nazis. You can criticize American policies as being like that of the Nazis, or any other country in the world, except Israel. That shows a clear viewpoint discriminatory basis for these prescriptions as articulated in the examples of the IHRA definition. The Department of Education announced investigations into 60 higher-ed institutions for violating Title VI for permitting or allowing antisemitic harassment. Some of the findings here will be that they permitted and didn’t respond to vociferous criticisms of Israeli policy.

MT: That’s kind of where the rubber meets the road with this controversy, right? Will a school like Columbia think it adhered to the requirements?

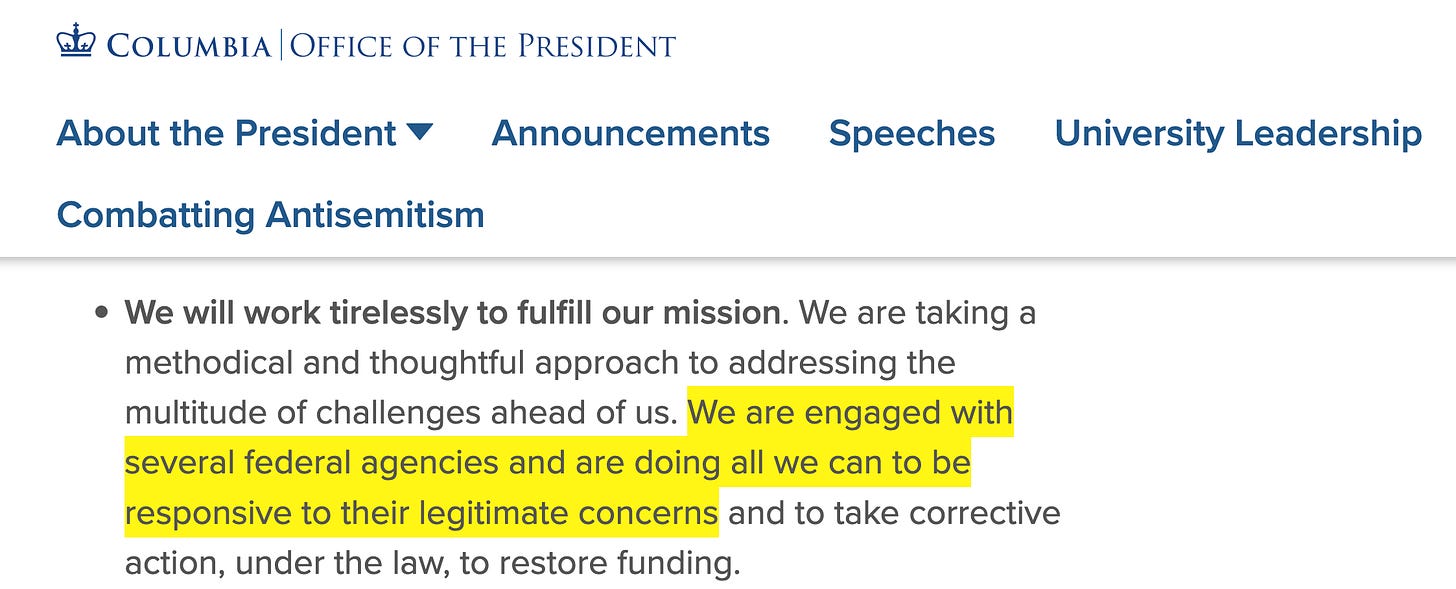

Tyler Coward: I don’t know that it does. It seems like some of these institutions have sort of admitted that things went too far and they didn’t respond. I think Columbia University’s statement the other night said, we are aware of the legitimate concerns of the government.

This was the statement after the announcement that $400 million in contracts were being revoked. There are institutions out there that have almost certainly run into serious Title VI problems by failing to respond to violence or other true discriminatory harassment that created a hostile environment. And when the institution fails to remedy a hostile environment and take standard, reasonable actions calculated to prevent the recurrence of that hostile environment, then they run afoul of federal anti-discrimination law.

MT: I’m assuming the First Amendment stuff in the other direction qualifies? I recall a demonstration where in order to get to a cafeteria you had to get a wristband from an activist group.

Tyler Coward: Blocking access to a cafeteria is not protected expression, nor is requiring some people to get a wristband and presumably excluding others based on some protected characteristic. We’ve heard examples of people who are a particular race or people of shared ethnicity being denied access to campus locations based on that status, which certainly violates Title VI.

Now, usually, historically, no higher ed institution has ever lost all its federal funding, which is the consequence of violating Title VI or Title IX. What usually happens is the government will open an investigation or even file a lawsuit against an institution, and then they resolve the lawsuit and the university agrees to adopt certain policies, and they will be monitored very closely for compliance. Usually it’s a resolution agreement and is subject to intense monitoring for three to five years. So the risk of losing all federal funding is sort of hanging over institutions. But it just hadn’t happened. But last week the Trump administration announced $400 million in cuts to institutions that didn’t follow that sort of investigation-plus-revocation process.

We’re concerned about that process. It hasn’t been clearly articulated by the administration what they’re doing. The statements from both Secretary Kennedy and Secretary McMahon announcing HHS and Department of Education contract and fund revocation relied on anti-discrimination rationales for doing so. We’re still figuring out the actual mechanisms for this revocation and the revocations paired with the administration’s reliance on executive orders. President Trump signed an executive order in 2019 that President Biden did not revoke. So it’s still on the books, requiring federal agencies to consider the IHRA when determining whether or not an institution is compliant with Title VI. This means that the federal government is going to be looking at constitutionally protected speech to determine whether an institution is compliant with Title VI. I think that creates an enormous chilling effect for students, because frankly, if an institution is forced to choose between censoring a student and possibly violating their First Amendment rights or losing all federal funding, they’re going to choose the former.

Settling a free speech lawsuit is pretty cheap compared to losing hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars flowing from the federal government. Just to put a bow on that: that’s exactly the wrong message that the federal government should be sending.

MT: A really key issue here is the IHRA definition, then. That’s baked into all of these controversies.

Tyler Coward: In Texas in late 2024 there was a case regarding the Students for Justice and Palestine chapter there being shut down by a special unit of the state police. During a protest at UT Austin, Governor Abbott signed an executive order in Texas referencing a statute that incorporated IHRA for the purpose of creating an antisemitism commission to study and report about antisemitism in the state of Texas. So IHRA was incorporated for the purpose of studying antisemitism, which is why IHRA was created in the first place. Ken Stern, the primary author of the IHRA definition, said that its language is intentionally broad to study allegations or incidents of antisemitism in Europe. They wanted to collect a lot of data to see what was going on.

He’s repeatedly said this was never intended to be used as a campus speech code. In fact, implementing this standard will restrict constitutionally protected speech. It was never intended to be used that way.

MT: “It backfires on so many different reasons,” he said in an interview with Nico Perrino.

Tyler Coward: Texas adopts it for a similar purpose of studying allegations or incidents in the state. And then Governor Abbott cited that definition in his executive order and said educational institutions have to use this standard for anti-discrimination purposes. And in the litigation the SJP brought targeting the executive order about the actions of the state police, the federal judge in Texas was extremely skeptical of IHRA and its constitutionality. The judge wrote that the plaintiffs were likely to succeed in proving that the executive order chilled speech in violation of the First Amendment. And he wrote that the court finds the incorporation of this specific definition of antisemitism is viewpoint discrimination. Now, the lawsuit is ongoing, so these are not rulings on the merits, basically dicta, but it is a clear indication that courts are seriously considering the implications of incorporating political speech about the state of Israel into anti-discrimination analysis.

MT: Okay. That’s one issue. Could we get into the DEI matters, the “Dear Colleagues” letter and so on?

Tyler Coward: With the DEI executive orders President Trump signed… one of the problems with initial litigation over these executive orders is that “illegal DEI” isn’t defined in the executive orders.

When the President says “illegal DEI” without a definition, that should raise people’s eyebrows and get them to think about and look into what the agencies are going to do. And helpfully, the president’s January 21st, DEI executive order exempted teaching in college classrooms from the content of the EO to make clear that course content wouldn’t be targeted.

And that’s something FIRE has been asking for. When the states have been reforming DEI bureaucracies at their institutions, that’s an important carve out that we like to see explicitly made clear, that this does not affect academic freedom rights, teaching in the classroom, research or publishing. Attorney General Pam Bondi — the DOJ has enforcement authority for Title VI — said in a memo, Hey, as we’re targeting illegal DEI, this does not mean cultural or historical observances such as Black History Month or International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Those sorts of things are not touched by this illegal DEI mandate that we have. And the clearest articulation of the administration’s new thinking about “illegal DEI” is pretty much in the context of race-conscious policies or affirmative action. The Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights issued a Dear Colleagues letter on February 14th that said, if an educational institution treats a person of one race differently than it treats another person because of that person’s race, the educational institution violates federal law. And they said this is an extension of the Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) case, the joint cases against Harvard and UNC, where the Supreme Court said that race-conscious admission policies are subject to scrutiny. They’re now taking that application to college admissions and applying it more broadly, to race-based scholarships, race-based housing, course assignments, and other things. They also targeted graduation ceremonies.

Those sort of race-separate policies that institutions have are now going to be suspect. FIRE doesn’t have an institutional position for or against affirmative action or affirmative action-type policies. But it strikes me as something that is an extension of SFFA from the context of purely admissions, and it seems like one that courts will likely agree to. This is a reasonable enforcement of civil rights law to take this rationale implied elsewhere. I suspect that when Trump says illegal DEI in the private sector, they’re going to try to use this SFFA ruling to target private employer affirmative action programs or race-based hiring programs. I suspect the courts will similarly respond when the litigation inevitably comes about. They will say, “Yes, this is a reasonable enforcement, this is a reasonable interpretation of federal civil rights laws.”

The problem with the OCR’s Dear Colleagues letter is that it also, while talking about these actual policies, talks about institutional programming. What does it mean for an institutional program to violate Title VI? Does that mean outside speakers that talk about DEI-related topics or affirmative action topics are presumptively not allowed? Well, we don’t know the full extent yet. We wrote publicly about OCR and its Dear Colleagues letter twice. Then on February 28th, they published a frequently asked questions document addressing some of the concerns raised by FIRE and others. That did a really good job of clarifying events at institutions and whether they could proceed, but it left open and unresolved the questions about institutional programs themselves — including outside speakers or institutional training — and when such institutional speech might cross a line. And I think OCR owes it to regulated institutions to make clear what they’re looking for.

MT: When it comes to institutional programming.

Tyler Coward: Yeah, exactly. They said one thing about cultural observances or heritage events, which is good. We’d seen institutions start canceling those things and we’re glad that that is off the table. But if an institution has an event celebrating or in support of DEI policies… private institutions have their own free speech rights. If OCR says that you can’t have an event on campus where the institution sponsors somebody who believes that DEI-related things are good, then that strikes me as viewpoint discriminatory.

And it’s hard to imagine where a speech from an outsider could create a hostile environment on campus such that OCR would launch an investigation under Title VI, but they’ve not made that clear. So our fear is that until that is clear, institutions will continue to self-censor, or cancel events, or even not sponsor them or what have you, in a way that degrades the extracurricular learning environment on campus and impermissibly chills the speech rights, particularly the speech rights of private institutions that have strong First Amendment rights of their own accord.

MT: You mentioned before about the exemption for classroom activities. There’s a huge controversy over the use of a long list of terms and research, with stories about schools purging terms in an effort to stay in compliance. Doesn’t that touch on the academic freedom issue?

Tyler Coward: Well, inside of a classroom professors have academic freedom rights that are also upheld by the First Amendment. We just don’t like government actors regulating the discussions going on in class. My colleague Aaron Terr published a piece for FIRE earlier this week about the First Amendment implications of government actors canceling research projects based on the viewpoint of the research. When awarding research dollars, the government certainly can take into consideration whether it wants to spend more money on this topic. They can say, “We are going to prioritize funding certain topics.” But where the First Amendment comes into play is when they are specifically saying, you are likely to have the wrong view on this and therefore we’re going to cancel it.

Now, this is really complicated because the government might say, “Hey, we are going to deprioritize funding social science or humanities research into DEI-related activities.” And that deprioritization might make sense when a new government comes into power. They may say, “Our grant money’s going to go to hard sciences.” We’ve seen some states say, “Hey, we’re going to spend more money on STEM and programs that graduate students with full-time employment.” And those are permissible, and viewpoint-neutral. “We’re prioritizing these particular programs. We think our research dollars are better spent in these ways.” Unfortunately, it seems like there has been some research caught up in these keyword searches… somebody I know in microbiology research had a proposal that mentioned “cell diversity” and that got caught up in this sort of shock-and-awe, break it, keyword search approach that we’ve seen. It’s imprecise, this targeting by keyword search phenomenon. Hopefully, those sorts of things will be remedied.

MT: But are they illegal? Is it illegal to do that?

Tyler Coward: That’s a good question.

MT: Some seem to think it’s a bit of a gray area. Others don’t.

Tyler Coward: I think the best thing to do is to direct you to Aaron’s piece (“Trump’s federal funding crackdown includes troubling attacks on free speech”). I think it’s complicated.

Also, take government authority through the Government Services Administration and the Federal Contracting Authority regulations where the government can issue stop work orders. One of the rationales for issuing stop work orders on government contracts is for the “convenience of the government.” There’s apparently — and this is all new to us — apparently really broad discretion for the government there to say, out of “convenience to the government,” you have to stop research. The contractors are eligible for recovering actual costs incurred and maybe some other things. But when the government says, we don’t want to do this anymore, they have pretty broad authority to do that.

I saw a Biden-era Education Department termination for the “convenience of the government” document where the government ended its contract with private collection agencies going after student loan borrowers. And basically the Biden administration was like, “We don’t want you hounding student loan borrowers anymore.”

So they just canceled the contracts out of convenience to the government. And the standard articulated there in that document was the government has a lot of latitude to terminate contracts for convenience. So it seems like they have pretty broad federal authority, and we would probably object if there’s evidence that the termination is pretextual for engaging in protected speech. I think we should be careful when research is canceled for fear that the research might show something the government doesn’t like. But I think the law is a little unclear.

MT: Thank you. Now, the last thing I was hoping to bother you about is this deportation issue which connects to Khalil. Let’s start with what are they allowed to do. I’ve seen in the Free Press that there’s an old case from 1904 that gives the government technical authority to do certain things, but if you’re essentially going in and announcing that you’re going to deport people because of protest-related activity, that kind of casts a pall over the whole thing, doesn’t it? I’m speaking irrespective of Khalil’s specific case. Or am I missing something?

Tyler Coward: What they can do under established case law is a little murky. There are some cases where the Supreme Court was skeptical of government power, and some where they’re not, where they’ve been permissive of the government authority. I think for our purposes, the normative arguments and maybe even legal arguments, if it comes to it, that FIRE is going to make, is that we’re not talking right now about people applying to come in. What we are talking about is people who are already here. And our strong normative position, and like I said, possibly legal too, if it comes to it, is that people in the United States, when they are here, have free speech rights that largely coordinate with those of American citizens, particularly people here on student visas who are here going to a school. They should be permitted to engage in what would be constitutionally protected protests or advocacy that would be protected for their fellow citizens. Denying them that opportunity and that right is a denial of the quintessential American university experience.

And if students on foreign visas here are afraid to engage in political speech or some sort of advocacy for fear of visa revocation and deportation, I think that sends exactly the wrong message to them, particularly students that come from more authoritarian regimes. If we want to teach them about American liberal democracy, we don’t hang this fear of deportation over their head while they’re here.

Now, of course, if they engage in actual unlawful conduct or violence or some other activity, that is an actual cause for deportation. If they’re expelled from their institution for engaging in some sort of unprotected conduct, or if they’re arrested for and found guilty of a particular crime, of course deportation is a likely outcome for them, but it shouldn’t be the outcome for them for engaging in speech.

The way the first Trump administration put it when they were talking about this in his first term, was they were trying to differentiate between people here on visas versus lawful permanent residents, people on green cards.

And they said, we don’t think there’s any authority at all to treat green card holders differently for engaging in protests or speech differently than American citizens. They sort of said the rights are fully co-extensive in this context. And Mr. Khalil, apparently, according to his lawyer, has a green card. So we’re past the student visa thing where they might try to flex more authority or assert more authority over folks who are here temporarily versus people who were here with permanent status.

We wrote yesterday to Secretary of State Rubio, Attorney General Bondi, Secretary Noem, asking them questions about why Mr. Khalil was being detained and the basis for his arrest..

When the administration signals that they’re going to arrest people with “pro-Hamas sympathies,” then arrests them and sort of disappear them for a while, it sends an incredibly chilling message to folks who do engage in political protests. Now they’re not sure what sort of speech crosses lines, to where the government might knock on their door in the middle of the night. And I think it casts an incredibly impermissible chill on speech for those individuals.

It may come out that Mr. Khalil has been involved in some sort of illegal conduct, but the government should make that clear sooner rather than later, and they haven’t done so yet.

MT: The thing that stands out to me is in a lot of “anti-extremism” or “anti-hate” laws around the world now, the standard is really vague.

Tyler Coward: It’s very broad and very imprecise. I think the DHS said that Khalil engaged in “activities aligned with Hamas.” What does that mean? How much pro-Palestinian or anti-Israeli advocacy does one have to engage in? Or what are the lines for “aligning” with Hamas? Marco Rubio had a similar statement that was extraordinarily broad. But they’re not even really saying what they’re looking for in terms of enforcement under these new directives. And that’s the chilling part. If we can get more clarity, maybe we can fix some of that.

MT: Thanks, Tyler.

Tyler Coward: Thank you.

Khalil shouldn't be deported for his speech. He should be deported for his crimes, of which there is ample evidence. Over at The Free Press today we've been discussing this and one comment was that Khalil was involved in negotiations with his university that he and his group would stop blocking access and occupying buildings if Columbia divested from Israel. That sounds like extortion. "I will stop breaking the law and harassing other students if you do what I want." For that reason, he should be deported. .... If this was a group preventing any other group of people (women, blacks, asians, gays) from lawfully entering a building, eating, or walking peacefully through campus, they would have been shut down on day one and likely prosecuted for harassment or threats. ... But thank you for a great interview Matt! Lots of good stuff here.

This bigot can say whatever he wants... Up to the point of inciting violence, which he has done. If someone showed up to campus in a white hood and a burning cross saying we should hang black people from trees, I wonder how different the reaction would have been. As for his deportation, if he's got a green card, not sure how you pull that off or even if we should. That said, I don't want to import more bigots like this guy.