FOIA Files: How Academics Identified "Misinformation" Around COVID-19

Another 836 pages from the University of Washington shows how researchers and "power users" in media cooperated to identify "misinformation" themes.

Last month, Racket received a new series of disclosures from the University of Washington. This latest production clocks in at 836 pages, and it’s almost too dense to adequately summarize here. For that reason, we’ve divided the revelations into three categories: (1) communications that broadly concern UW’s crusade against “misinformation” and “disinformation,” (2) communications that concern UW’s relationships with government actors, and (3) communications that concern UW’s analysis of data from social media platforms. The most pertinent communications are summarized in this article. As usual, you can read the unabridged documents in the Racket FOIA Library.

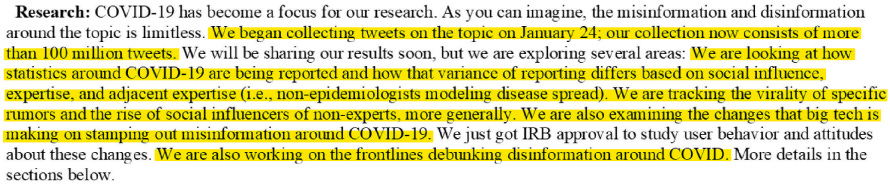

Most of the emails regarding “misinformation” and “disinformation” pertain to COVID-19. On March 20, 2020, just days after states had started implementing lockdown orders, UW professor Jevin West emailed his peers an update on the school’s Center for an Informed Public. According to West, the CIP had put together a collection of 100 million COVID-related tweets, with much of the Center’s research centered around social media companies’ efforts to combat COVID “misinformation.” West credits co-author and biology professor Carl Bergstrom with popularizing the “flattening the curve” strategy in venues like the World Economic Forum.

The following month, Starbird directed colleagues to a research study from the South China University of Technology. According to Starbird, conservatives like Tucker Carlson were using the study to “push a ‘Chinese-created virus theory.’”

Given what we now know about the provenance of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Center’s focus on debunking such “misinformation” casts doubt on both the organization’s credibility and its overall mission. Has history vindicated Carlson’s assessment? Racket’s own collaboration with Public showed there was significant doubt about the “zoonotic origin” theory even among the scientists working most closely with American health authorities, pointing again to a key distinction between journalism and “anti-disinformation” programs: The former prizes skepticism, while the latter views deviation from official statements as inherently problematic.

“A MODEL FOR THE COUNTRY FOR HOW TO COME TOGETHER ON THIS ISSUE”

The new production also contains a number of emails that concern UW’s interactions with state actors. The most striking might be from October 24, 2019, two months before the CIP officially launched. That was when law professor and CIP co-founder Ryan Calo told his peers that he had been invited to have coffee with U.S. Senator Maria Cantwell. Calo posed a very striking question to his colleagues: “Are there specific things we want to stress to her about the Center?”

Jevin West’s response underscores how expansive the CIP’s designs were (emphasis ours):

I would stress that we see this as a state wide effort and how we could be a model for the country on how to come together on this issue.

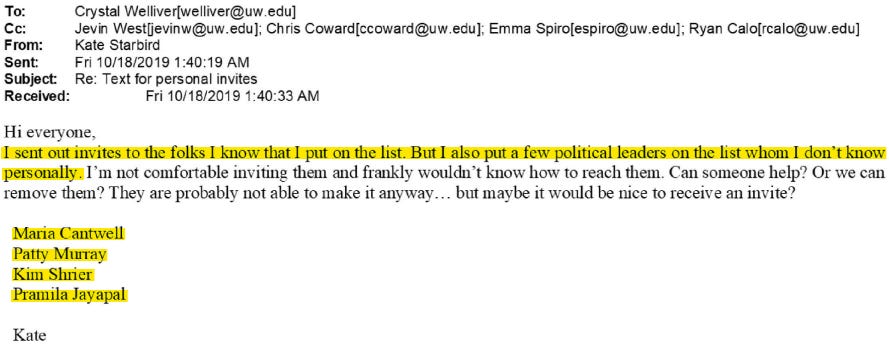

Funnily enough, just the week before, Starbird recommended inviting Cantwell, along with Senator Patty Murray and Congresswomen Kim Schrier and Pramila Jayapal, to the CIP’s grand opening event on December 3.

The CIP hoped to make inroads with federal lawmakers, thereby gaining nationwide traction, not to mention political and financial backing. The fortuitous timing of Calo’s meeting with the junior U.S. senator from Washington provided the Center with a golden opportunity to ingratiate itself with Congress.

Calo told Racket that he and Cantwell did not discuss the CIP during their meeting. According to Calo, Cantwell “wanted to talk about consumer privacy, as she was co-sponsoring a bill on that subject.”

“HOW TO ADAPT STATUTES AND RULES… TO FIT THE MODERN WORLD OF DIGITAL COMMUNICATIONS”

Days after the CIP officially opened its doors, Calo received an email from William Downing, a retired judge appointed to the Washington Public Disclosure Commission (PDC). While stressing his opposition to censorship, Downing told Calo that he and his fellow commissioners were trying to figure out “how to adapt statutes and rules (written with print and broadcast media in mind) to fit the modern world of digital communications.” Downing then expressed an interest in “taking guidance from the things the CIP learns.”

A government official soliciting feedback on the best means of crafting legislation to combat “misinformation” and “disinformation”? Downing’s email almost seems to presage the Biden administration’s Disinformation Governance Board. Given the PDC’s interest in modifying the law in response to new media, his insistence that he opposes censorship comes across as superficial.

Many of the emails in this production also focus on UW’s efforts to gather and interpret data from social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, 4chan, and 8chan. Both before and after the CIP’s launch, the UW team was committed to gathering as much social media data as possible, be it directly from the tech companies themselves, through “web scraping,” or using tools like DiscoverText.

“THE GO-TO PLACE FOR DIRECTION”

UW’s relationship with Facebook is instructive. On May 25, 2019, Calo asked if the CIP should weigh in on Facebook’s refusal to remove the famous “Drunk Nancy Pelosi” video. West stated that it should and expressed hope that the Center would become “the go-to place for direction on these kinds of events.” Starbird concurred and went further, stating that once the Center became operational, it could draft statements and dispatch representatives to talk to the media.

A week later, Calo emailed his peers to tell them about his experiences at a conference in Berkeley. According to Calo, he met two Facebook employees, Elaine Sedenberg and Naomi Shiffman, who were responsible for “getting academics access to the company’s data.” (Sedenberg previously served as a science policy fellow at the Institute for Defense Analyses, while Shiffman is a former J Street organizer who currently holds a fellowship at the Atlantic Council.)

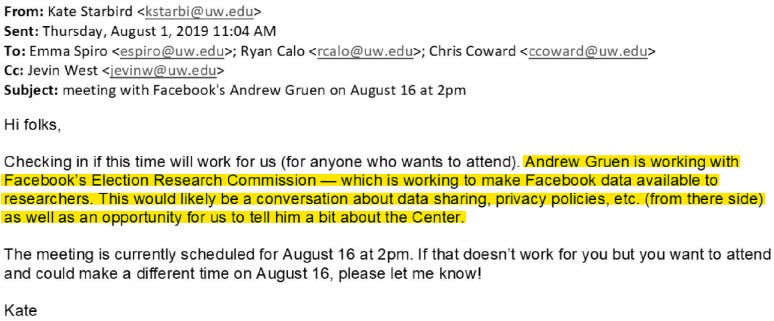

In August, Starbird asked her fellow CIP members to join her for a meeting with Facebook’s Andrew Gruen, who was working to formalize a data sharing program with university researchers. The meeting would also provide the UW team with an opportunity to introduce the Center and its objectives to Facebook.

“POWER USERS”

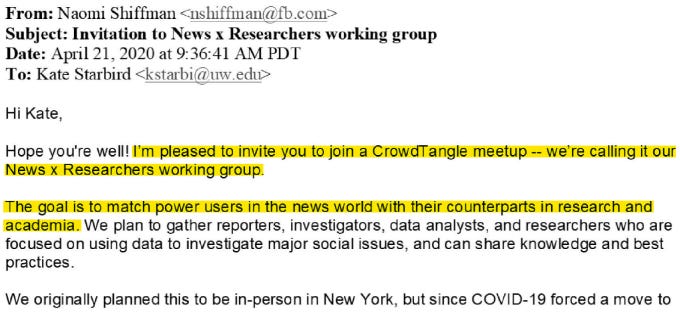

The following April, Naomi Shiffman would invite members of the CIP to a virtual meeting in which participants would learn more about CrowdTangle, Facebook’s information tracking tool. Shiffman said that the purpose of the working group was to “match power users in the news world with their counterparts in research and academia.” Among the attendees would be representatives from the Stanford Internet Observatory, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and NBC News.

Meta recently announced that it was phasing out CrowdTangle, a decision that sparked a massive outcry from “anti-disinformation” researchers. Many of them signed a letter urging the company to maintain the tool in advance of the 2024 presidential election. Interestingly enough, none of the CIP researchers are among the signatories.

“FROM THE CHANS TO THE PLATFORMS”

These disclosures also shed more light on UW’s relationship with Twitter. On September 15, 2017, postdoctoral researcher Peter Krafft responded to a paper Starbird sent him. Krafft proposed using Twitter’s “firehose” API to search for keywords pertaining to that August’s Unite the Right rally. From there, Krafft hoped to model how certain narratives about the events in Charlottesville spread from Twitter to Reddit, 4chan, 8chan, and other platforms.

Two years later, the Center was receiving unhashed data sets directly from Yoel Roth, then the head of site integrity at Twitter. In fact, the CIP was on a mailing list for researchers cleared to receive election integrity data from the platform.

The CIP team was soon in the habit of using its access to Twitter’s search API to conduct research for journalists like The Washington Post’s Greg Miller. That May, Starbird asked fellow CIP co-founder Emma Spiro for her help with a project that would help the group “understand how to support journalists in doing data analysis (which aligns with the CIP mission).”

“HASHTAGS LIKE #JOEBIDEN AND #BERNIEORBUST”

Of course, all of this pales in comparison to the work the CIP was doing with Twitter data during the summer of 2020. That June, Starbird instructed UW senior data engineer Paul Lockaby (formerly of research and development outfit MITRE) to comb through the 2019 and 2020 data sets they had gathered and search for tweets that mentioned Democratic presidential candidates Joe Biden (“Biden”) and Bernie Sanders (“Bernie”).

Less than a week later, Lockaby told Starbird and Spiro he’d written a program that could provide him with a Twitter user’s last 3,200 tweets and all of their followers. Lockaby said that he was using the program on a list of epidemiologists and public health officials and saving the results to his home directory. According to Lockaby, he had also established subdirectories where CIP members could save tweets about the coronavirus pandemic and Black Lives Matter protests.

The Center for an Informed Public’s coordination with social media giants offers a microcosm of the organization’s influence. At this point, it’s impossible to deny that the CIP sought a significant role in shaping the future of a free Internet.

Among this FOIA production’s 836 pages, you’ll find disclosures about the CIP’s interactions with Facebook, its work with the Department of Defense, and an effort by TikTok’s “anti-disinformation” advisory council to recruit Starbird.

FESTIVAL DISASTERS On September 21, 2016, tourism and event researcher Christine Van Winkle of the University of Manitoba emailed Starbird to discuss her research on “social media use during festival disasters.” Van Winkle also asked Starbird if she could tour the Information School’s Social Media Lab during an upcoming visit to UW. (See page 718.)

UW ON FACEBOOK: “PERSONAL/PROFESSIONAL OBJECTIONS TO THEIR PRODUCT” On December 20, 2018, Alex Pompe, a research manager on Facebook’s Data for Good team, reached out to CIP co-founder Chris Coward to discuss the possibility of sharing map data with Coward and his colleagues. Pompe later cited Facebook’s partnerships with Columbia, Harvard, Northeastern, Oxford, and Stanford as examples of past collaborations that had proven successful. In February, Starbird told Coward that she was unwilling to pursue “direct financial support” from Facebook because of “personal/professional objections to their product and policies,” but she stated that she’d be “willing to pursue data collaborations” and was “happy to work with others who are receiving funding from them.” (See pages 532 through 535.)

DOD GRANT? On March 18, 2019, in an email with the subject line “Re: Facebook Moderators Grant,” Saiph Savage, the director of Northeastern University’s Civic A.I. Lab, informed the CIP that its Department of Defense grant submission had entered its second phase. (See page 524.)

SYRIA DIRECT On March 29, 2019, UW communications professor Karen Fisher reached out to the UW team to introduce her “translator and fixer in Amman,” Salah Falyoun, and to discuss her work interviewing journalists with the Syria Direct news agency. Fisher told the team she was “identifying leads for data science analysis,” prompting Starbird to reveal that UW’s infrastructure “makes Twitter data collection very easy.” (See pages 508 and 509.)

INSTAGRAM IMPACT On May 10, 2019, Starbird suggested that the UW team respond to Instagram’s call for research proposals that would help the platform better understand its “impact on human well-being.” (See page 494.)

“USING BLEACH TO TREAT AUTISM” On May 21, 2019, Starbird alerted West to a tweet from Twitter user @Crossfit4life1 in a thread about “using bleach to treat autism.” Perhaps Starbird chose to highlight this random tweet because it tagged “anti-disinformation” expert Brandy Zadrozny, but her email calls into question the CIP’s commitment to the scientific method. Rather than conduct a controlled study using a random sample of tweets, Starbird seemed to be in the habit of haphazardly selecting tweets from anonymous users and citing their mere existence as proof of the intractability of online “misinformation.” At the same time, Starbird’s email underscores the CIP’s fidelity to the belief that one should always defer to scientific, political, or media authorities. Read Matt Taibbi’s article on “doing the math” for more on this phenomenon. (See page 450.)

DARK PATTERNS AND DATA SHARING On July 17, 2019, Calo emailed his colleagues to tell them that an interdisciplinary delegation from Facebook was thinking about visiting the UW campus to discuss dark patterns and data sharing. (See pages 399 and 400.)

VACCINE MAP On February 12, 2020, Dr. Benji Dossetter, a pediatrics resident at Seattle Children’s Hospital, emailed Calo to discuss using Twitter data to map the correlation between MMR vaccine rates and retweets of vaccine “misinformation” across Washington state, presumably to make the argument that the spread of “misinformation” correlated with lower vaccination rates. (See pages 216 through 218.)

“REPUTATIONAL LAUNDERING” On February 17, 2020, a lawyer representing TikTok reached out to Starbird to ask if she was interested in joining the company’s “anti-disinformation” advisory council. This prompted Starbird to ask Calo for advice, citing the platform’s “connections to the Chinese government.” According to Starbird, she had received a similar invitation from Twitter. Calo cited “influence over a major platform” as a possible benefit of accepting, but he also warned against the perils of “potential reputational harm” and “reputational laundering.” Starbird later suggested that she wouldn’t accept the role. (See pages 176 and 177.)

“WE’LL WANT TO INFLATE OUR ESTIMATES” On March 6, 2020, Starbird told Paul Lockaby that the CIP would need an annual storage allowance of about twenty terabytes for its collection of Twitter data, but clearly expected their storage needs to grow. (See page 263.)

NEWSGUARD SHOUT-OUT On March 19, 2020, Starbird suggested that the CIP use NewsGuard’s Misinformation Monitor newsletter to track “misinformation” narratives surrounding the coronavirus pandemic. (See page 283.)

“CORONA VIRUS, TWO WORDS” On April 10, 2020, Starbird wrote that the CIP had infrastructure set up to “search Google for any number of terms.” Calo later added “‘corona virus,’ two words” to the Center’s list of key terms and wondered “if there were a bigger delta between results based on search terms in different states, or between urban, sub-urban, and rural areas.” According to Starbird, this infrastructure also allowed them to see changes in search results over time. (See pages 201 through 203.)

To access Racket’s full library of productions pertaining to the University of Washington, click here.

Why is it the first impulse of all these supposedly smart and well intentioned people is to limit and control what other people say? Goddam karens, all of them.

From day one I felt we were being lied to. So I acted accordingly and ignored every single edict re Covid. I was right. Those who swallowed the panic, shame on you. You gave away your autonomy for no return.