Does America Hate the "Poorly Educated"?

Michael Sandel's "The Tyranny of Merit" doesn't say it, but the pandemic has become the ultimate expression of upper-class America's obsession with meritocracy

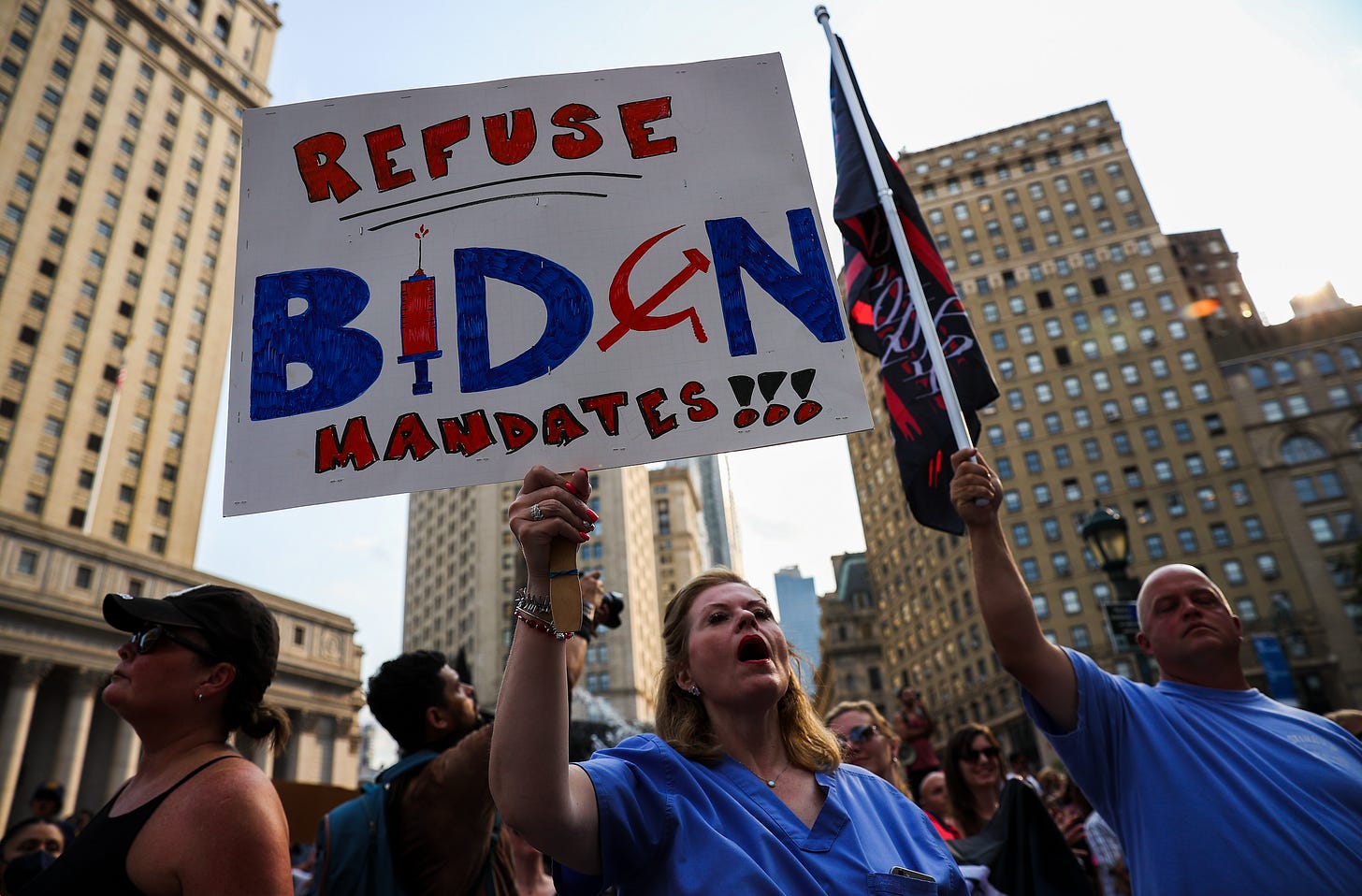

It was impossible to mistake the tone of Joe Biden’s announcement of a vaccine mandate last week. It was an angry speech, which started by explaining that “many of us are frustrated with the nearly 80 million Americans who are still not vaccinated,” and went on to announce that “our patience is wearing thin,” and “your refusal has cost all of us.” Biden, not normally one for oratorial effects, even conveyed a sense of barely contained rage by muttering, “Get vaccinated!” as he walked off the stage.

“Enjoying the angry Dad vibes from this Biden speech,” came the cheerful comment of former Justice Department spokesman and MSNBC analyst Matthew Miller:

Who’d attracted Biden’s anger — the unvaccinated — was clear. The why was more confusing. The president decried how “the unvaccinated overcrowd our hospitals… leaving no room for someone with a heart attack or pancreatitis or cancer,” a legitimate enough point. But after reassuring those who’d “done their part” that just “one out of every 160,000 fully vaccinated Americans was hospitalized” this summer, Biden nonetheless explained that “a distinct minority of Americans” is “causing unvaccinated people to die.” He added: “We’re going to protect the vaccinated from unvaccinated co-workers.”

As many noted, the statements were contradictory. If the vaccine really is that effective, the overwhelming consequences of of any failure to get vaccinated will be borne by the unvaccinated themselves. But Biden’s speech was as much about directing anger as policy. The mandate was an extraordinary step, but Biden’s unique — and uniquely strange — rhetorical setup, which framed the decision as a way to stop “them” from doing “damage” and killing “us,” was just as big a story.

The arrival of Covid-19 has exacerbated a troubling divide that’s been growing in America for decades, and is elucidated at length in Michael Sandel’s recent The Tyranny of Merit. The book tells a politically unsettling story about meritocracy in America, one that runs counter to prevailing narratives on both the left and the right. Though mention of Covid-19 is limited to a few paragraphs in a new prologue, the pandemic in many ways has become the ultimate test case of Sandel’s thesis: that we Americans have been so conditioned to believe that winners deserve to win that we’ve found ways to hate losers of any kind as moral failures, even when life is at stake, and especially when lack of education is seen as a factor.

It’s not remotely the same kind of book, but The Tyranny of Merit does follow up on themes in Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism. Lasch’s late seventies premise described American society devolved into a ceaseless all-against-all competition on all fronts, from the professional to the physical to the social and sexual and beyond. Moreover, Lasch wrote, if the original “American dream” was imbued with at least some vague ideas that success should be tied to virtues like thrift, discipline, and wisdom, by the disco age “the pursuit of wealth lost the few shreds of moral meaning.”

In the time since Lasch’s iconic treatise, though, relentless messaging campaigns emanating from both sides of the political aisle re-emphasized the idea that material success was tied to moral character. Ronald Reagan evangelized the idea that poverty was mostly a deserved state, and government at most owed those who weren’t to blame for their own problems. When Bill Clinton came along, he took Reagan’s finger-wagging moralizing and re-cast it in the cheery new technocratic language of global capitalism. “We must do what America does best,” Clinton said at his inauguration. “Offer more opportunity to all and demand more responsibility from all.”

Clinton’s formula was really Yin to Reagan’s Yang: in a world that offered more “opportunity,” there was now even less excuse for failure. We forget, because the pre-9/11 world seems so long ago, but Clinton-era editorialists spent much of the late nineties hyping the opportunity gospel. We were told a combination of the Internet and an increasingly integrated international economy created vast new worlds of material possibility, for those willing to “fill the unforgiving minute” and run the race. “If globalization were a sport,” wrote an exultant Thomas Friedman in 1999, “it would be the 100-yard dash, over and over and over. And no matter how many times you win, you have to race again the next day.”

Onetime labor parties paradoxically were the biggest boosters of the new hyper-competitive global economy, whose central feature was forcing Western workers to face off against masses of laborers in China, South Asia, Mexico, and other places where political rights were, shall we say, less of a priority. As the stress on former blue-collar workers intensified, politicians often sold the public on the idea that higher learning was their Golden Ticket out of the miseries of debt, higher medical costs, and especially social immobility.

By the time Barack Obama came along, it was axiomatic among the cosmopolitan set that anyone with enough ingenuity and entrepreneurial energy should be able to get ahead. Sandel amusingly points out that Obama often culled from a Sly and the Family Stone song in describing his vision of modern American capitalism, using the phrase “You can make it if you try” 140 times during his presidency:

The explosive and uncomfortable message at the heart of The Tyranny of Meritocracy is the idea that the resulting political divide is now less about ideology than education. Sandel deserves credit for taking on a subject that almost no one in high society wants to hear about, let alone those in the academic world. Forget red versus blue: he shows the real gulf is between those who have diplomas, and those who don’t. The subtext is that people with the right degrees deserve to be rich, and have health insurance, and good schooling for their kids, and dignified work, while those who threw away their books after high school deserve failure, in the same way smokers deserve lung disease — especially if they make unsanctioned political choices.

From the 1940s through the 1970s, those without university backgrounds reliably voted Democratic, but center-left parties here and in Europe have since become more upper-class in their orientation, while those without diplomas overwhelmingly back right-wing or nationalist parties. Sandel notes that the “most conspicuous casualties” of recent populist uprisings around the world have been “liberal and center-left political parties,” which makes sense given the flipped demographics.

The statistics in America on this score are incredible. In the 1992 presidential race, the thirty districts with the highest percentage of diploma-holding voters split evenly between Republicans and Democrats. By the 2018 midterms, all but three of them voted Democratic. In 2016, Hillary Clinton did better than Barack Obama in 48 of the 50 districts with the highest percentage of college graduates, but did worse than Obama in 47 of the 50 districts with the lowest percentage.

Moreover, university graduates now dominate positions of influence in a way not seen for generations. If even in the early 1960s a fourth of all members of congress lacked a college degree, by the 2000s, 100% of all Senators and 95% of House members had one. Also, as Sandel notes, almost no one in a position of power in today’s United States knows what it means to have ever had a working class job.

“In the U.S., about half of the labor force is employed in working class jobs, defined as manual labor, service industry, and clerical jobs,” he writes. “But fewer than 2 percent of the members of congress had such jobs before election.”

Meanwhile, despite the fact that universities are more diverse with regard to race and gender than ever, from a class perspective they remain symbols of iron exclusivity. “At Harvard and other Ivy League colleges,” Sandel writes, “there are more students from families in the top 1 percent… than there are in the bottom half of the income distribution combined.” He notes that two-thirds of the students at Harvard and Stanford come from the top fifth of the income scale, while “despite generous financial aid packages, fewer than 4 percent of Ivy League students come from the bottom fifth.”

Sandel starts his book talking about the great college admissions scandal of 2019, which engulfed thirty-three parents (including actress Felicity Huffman) in an all-time revolting scheme to bribe a path for kids into prestige schools. One parent paid $1.2 million to get his daughter into Yale on a soccer scholarship, despite the fact that she didn’t play soccer.

That scandal was about more than a small group of parents wanting to spare their kids what Sandel calls “the precarity of middle-class life.” Most of the offenders could afford to simply buy affluent futures for their kids, via trust funds if need be. More significantly, they were trying to buy the “borrowed luster of merit.” Why was that so important? Because increasingly in the last decades, lacking the right credentials began to be seen as an acute moral failing.

Sandel calls it the “last acceptable prejudice”: credentialism, i.e. looking down on people without certificates and degrees attesting to expertise, status, accomplishment. The author, who teaches Political Philosophy at Harvard, put it this way (emphasis mine):

At a time when racism and sexism are out of favor (discredited though not eliminated), credentialism is the last acceptable prejudice…

In a series of surveys… a team of social psychologists found that college-educated respondents have more bias against less-educated people than they do against other disfavored groups. The researchers surveyed the attitudes of well-educated Europeans toward a range of people who are typically victims of discrimination—Muslims, people of Turkish descent living in Western Europe, people who are poor, obese, blind, and less educated. They found that the poorly educated were disliked most of all.

Similar studies in America also showed respondents had the most negative feelings of all about the less-educated. Unfortunately, “smart” in the last decades also began to mean different things to different sectors of American society.

To politicians of the pre-Trump era, Wall Streeters were whip-smart experts. To the rest of America, they were depraved amoral scum who’d robbed the country and whose walls full of degrees only added to the insult. The swindlers at Enron were the “smartest guys in the room,” and Goldman, Sachs bankers were the “smartest guys on Wall Street,” but this smartness didn’t count for much among the people wiped out after 2008. The public seethed even more to see that the supposedly genius-level intellects of bank executives mostly got used to ask pals in government to bail out their sociopathic, and often comically stupid, investment decisions.

All over, “smart” lost its luster. “Smart” bombs turned out mainly to be efficient machines for creating civilian casualties, “intelligence” became a synonym for grotesque security oversights and mass law-breaking, and commercial media especially became a place where the ordinary person could see the almost total moral uselessness of advanced degrees. In one of Sandel’s most interesting passages, he talks about the conclusions the average person drew from watching the increasing vapidity of “what passes for political argument” in public discourse:

Citizens across the political spectrum find this empty public discourse frustrating and disempowering. They rightly sense that the absence of robust public debate does not mean that no policies are being decided. It simply means they are being decided elsewhere, out of public view…

In other words, audiences correctly grasped that the stupidity of political debates on TV did not mean America’s actual politics were stupid. They just surmised the more substantive debates were being hidden from them, with the assent of the news media. This only increased their fury toward all of these groups.

After the election of Donald Trump, upper-class America began to look down at the uneducated not just for the implied offense of not working harder to get ahead, but for their political choices, now seen as ignorant, bigoted and protective of unearned privilege. Article after article appeared after 2016 claiming that fear of “loss of status,” not economics, explained the rage emanating from the heartland.

Some of these analyses played out like extensions of nineties-era Tom Friedman-style opportunity rhetoric, which suggested that only those who resisted “integration” with the rest of the planet, or relied on their governments “to protect them from… creative destruction,” would fall behind in the dynamic digital economy. Post-Trump, the twist was that those without degrees in flyover country were rebelling not just against having to compete with educated Chinese and Indians abroad for jobs, but against increased opportunities for women and minorities at home. Like white ballplayers after Jackie Robinson, they were bitter about losing undeserved status, and banded together behind bigots like Trump, who promised to shut borders and restore ancient hierarchies.

According to Sandel, years of meritocratic messaging turbo-charged this political controversy with a miserable trick of basic psychology:

Protest against injustice looks outward; it complains that the system is rigged, that the winners have cheated or manipulated their way to the top. Protest against humiliation is psychologically more freighted. It combines resentment of the winners with nagging self-doubt: perhaps the rich are rich because they are more deserving than the poor; maybe the losers are complicit in their misfortune after all.

As Sandel notes, Trump was wired into these politics of humiliation and never invoked the word “opportunity,” which both Obama and Hillary Clinton made central, instead talking bluntly of “winners” and “losers.” (Interestingly, Bernie Sanders also stayed away from opportunity-talk, focusing on inequities of wealth). Trump understood that huge numbers of voters were tired of being told “You can make it if you try” by a generation of politicians that had not only “not governed well,” as Sandel puts it, but increasingly used public office as their own route to mega-wealth, via $400,000 speeches to banks, seats on corporate boards, or the hilariously auspicious, somehow not-illegal stock trading that launched more than one member of congress directly into the modern aristocracy.

The Tyranny of Meritocracy describes the clash of these two different visions of American society. One valorizes the concept of social mobility, congratulating the wealthy for having made it and doling out attaboys for their passion in wolfing down society’s rewards, while also claiming to make reversing gender and racial inequities a central priority. The other group sees class mobility as entirely or mostly a fiction, rages at being stuck sucking eggs in what they see as a rigged game, and has begun to disbelieve every message sent down at them from the credentialed experts above, even about things like vaccines.

The eternal squeamishness Americans feel about class will prevent this topic from getting the attention it deserves, but the insane witches’ brew of rage, mendacity, and mutual mistrust Sandel describes at the heart of American culture is no longer a back-burner problem. Tension over who deserves what part of society’s rewards, and whether higher education is a token of genuine accomplishment or an exclusive social rite, has become real hatred in short order. In the pandemic age, Americans on either side of the educational divide have moved past rooting for each other to fail. They’re all but rooting for each other to die now, and that isn’t a sentiment either side is likely to forget.

Our hyperdrive to demonize The Other in terms of education and class is the iceberg into which the Titanic is being steered.

True merit--knowing how to do things, deal with all kinds of people and situations, and the wisdom to know when and when not to do them--is a worthy goal in life. But college degrees and credentials have little to do with that kind of merit, as reflected on our generally piss-poor Governing and Chattering Class.

Matt, it's much more complex. Everything you address is a symptom, not a root cause.

The abject failure of college education arises out of a misunderstanding of what a college degree means and who needs them. In a factory of 1,000 workers, there are probably 15 people whose college education has some value. That's my upper-limit estimate. We observed that these people made more money than those without college degrees, and decided that if everybody just got college degrees then everyone would make more money. That's not the way it works. You first need to create positions requiring college degrees, not throw college degrees at positions. So, everyone was told "Go to college." And loaned the money to do so, without ever examining whether the degree had any commercial value, or even if the individual should go to college at all.

People were told to "follow your dreams," and no worse advice was ever given. "I want to be a marine biologist!" sounds good. What are your realistic prospects of getting a job in the field? Close to zero. A degree in accounting comes with a job at the end. Invented disciplines such as intersectional geriatric Innuit and learning-disabled pregnant East Absurdians get loans. The politicians boast about helping everybody get college degrees and, and when the whole thing blows up, Ronald Reagan gets blamed. Or curmudgeonly old white men. Or anybody but the public school teachers and the parents who failed to teach their children financial literacy, and the numbskull government clerks look great while chaining our children to a lifetime of debt.

We don't need a lot of college graduates. I have a bachelors in Spanish and Music, a Masters in high-energy laser physics, and a medical degree from a German University. My brother in law is an elevator mechanic. His net worth is many times mine. I should have skipped college and become a plumber.

Physical therapists decided that they would make more money if they got Doctorates. So, the entry-level degree is a doctorate. That does nothing to increase the need for physical therapists nor the money to pay for their services. Pharmacists followed suit. The entry-level degree is a PharmD. That creates no new money to pay for their services, just shoved more money into colleges' pockets.

We graduate people with estimable degrees in aromatherapy or gender studies and when they are lucky they get promoted to barista five years after graduation. Life is about choices, informed choices, and parents, teachers and federal loan officers hide information from those seeking degrees. When they wake up to reality, few of them recognize the moral hazard to which they had succumbed. Instead, they blame baby boomers (I'm one) and uneducated stupid right wing bigots, society, and look everywhere but a mirror. I've been told on-line multiple times I'm useless and should die to get out of the way of the deserving.

I've devoted the last 20 years of my life to working with entrepreneurs, coaching them through how to turn their life experiences into jobs they own. Regardless of race, creed, sex, gender identity or anything else, those that put in the work reap the rewards. The last time I was charged out to a client as a management consultant I was billed at $500/hour. I gave that up to help those who had been crucified on the cross of "progressivism." Millenials assume I am uneducated because I extoll the virtues of entrepreneurism. That means I'm white, male, a racist, a sexist, an homophobe, hate all foreigners, and the only reasons that I fail to agree with every jot and tittle of one of these Masters of the Universe's wise pronouncements about his or her moral superiority are ignorance, stupidity or malice. I posted widely on the coronavirus in January 2020 as soon as I learned that Taiwan had closed its borders. The WHO was venerated, and I was banned from many platforms for pointing out that this is an extraordinarily contagious common cold virus. We needed to focus all protection efforts on the most vulnerable: the elderly and obese, and leave everyone else alone until we had more information. I'm still shunned for advising people not to get a vaccination until they have talked to their family physician if they are under 20, or pregnant, or immune-compromised, or have an autoimmune disease. None of these people should be vaccinated by anyone other than a physician. I am fully vaccinated, had breakthrough COVID, and two hospital stays exposed me to how much Kool Aid nurses have downed.

COVID19 is the gift that can't stop giving. Remember bending the curve in two weeks? Now a college in Connecticut has 100% of staff and students vaccinated and mandates they wear masks outdoors, where it is almost impossible to get infected. There is no end to the lockdown, and that's exactly what the authoritarians want.