Twitter Files Extra: How the Files Could Help Incoming Investigators

Two years ago, Twitter emails offered voters a peek at state censorship. Now, they can be a road map for incoming investigators. Where they might search for wrongdoing

In May, 2022, an agent from the FBI’s San Francisco office sent Twitter Trust and Safety Chief Yoel Roth a formal inviation to join an “exclusive group” for “an Executive-level roundtable” on June 8th of that year that would include the Assistant Director of the FBI’s Cyber Division, Bryan Vorndran. Roth was unavailable, so he passed the invite to other team members, who balked for a strange reason.

“I’m guessing they’re probably not being super-careful with the Covid protocols, so unfortunately I think I should pass,” said one Twitter employee.

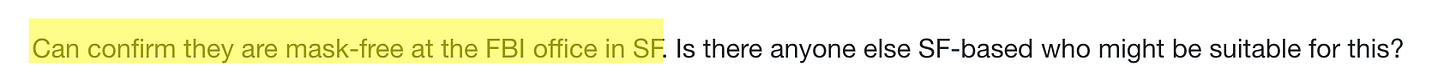

“Can confirm they are mask-free at the FBI office in SF,” Roth wrote:

Roth added, however: “I’m pushing a little just because the FBI SF folks have been great partners, and sincerely are eager to foster more collaboration…”

This seeming offhand comic exchange in the Twitter Files featured a Justice Department attachment:

In its invite, the FBI named another “roundtable” attendee, a White House National Cyber Director. This helped us understand that the FBI at least sometimes mediated with Twitter on behalf of the White House. It also had names and email addresses of two more San Francisco FBI employees (not shown above), one titled “Private Sector Coordinator.” Most importantly, it contained a line about the Bureau valuing its relationship with Twitter “directly and through the Domestic Security Alliance Council (DSAC).”

When we ran a check on “DSAC,” we found the FBI sometimes passed sensitive information to Twitter through a “DSAC Portal,” a secure line through which executives were briefed on everything from Covid to the UK government’s call to remove more “covert hostile state material,” especially related to Russia. This note below arrived shortly after the events of January 6th:

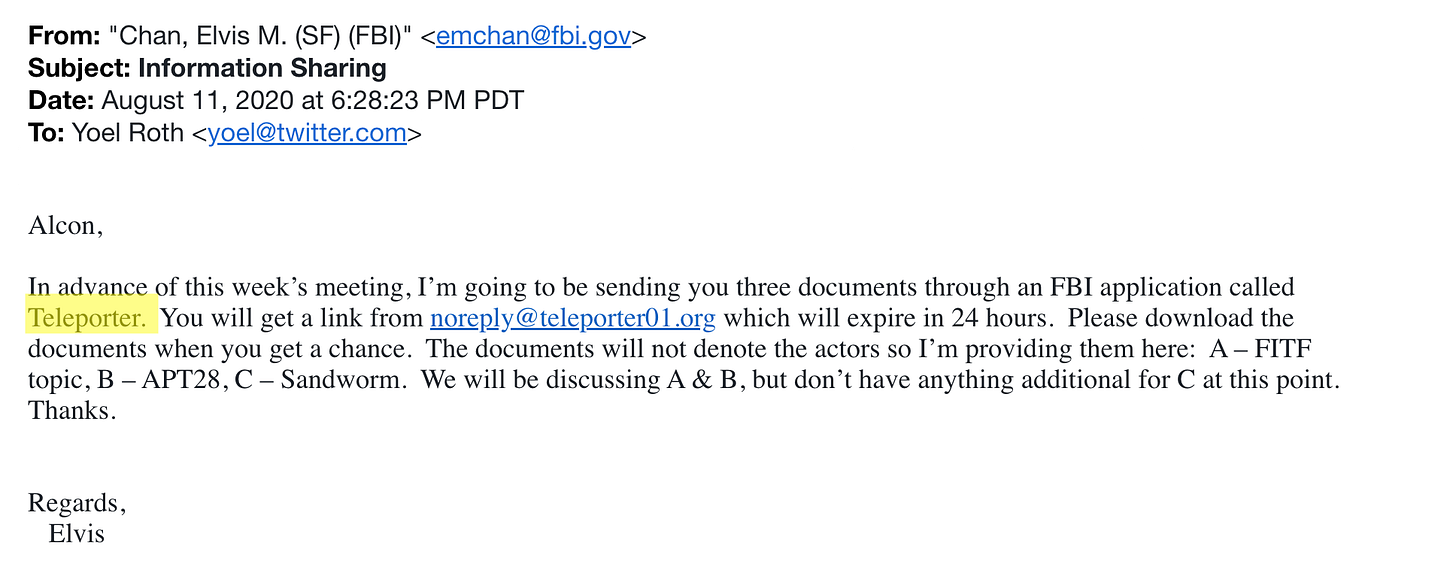

Twitter Files reporters couldn’t get access to those documents or most of the materials sent through the “DSAC Portal.” We similarly got little of the information that came through Twitter’s “Partner Support Portal (PSP),” created to “streamline” moderation requests from outside sources that eventually included the Biden White House. Both were distinct from Teleporter, a one-way Mission Impossible-style line through which Twitter execs received information via an FBI link that would vanish “in 24 hours.” Michael Shellenberger found an email suggesting three potentially important documents were sent to Twitter via Teleporter on April 11th, 2020, before the Hunter Biden laptop story broke:

It would have been nice to get those documents. Is it still possible?

It’s been rumored Executive Branch teams in the next administration may be considering new investigations into government censorship, perhaps with cooperation of Congress. If any transition officials are on the fence about undertaking such a job, they should know there’s a lot of information in unpublished Twitter Files that could be used to speed up/simplify such queries. The DSAC Portal, Teleporter, and Twitter’s PSP are just three communications channels whose contents we couldn’t see, but someone with more complete access might. We have names, dates, and email addresses ready to make the checking easy.

Below is an abridged list of leads/items from the Twitter Files I hope someone follows up on from the government side:

The Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI). Twitter and as many as 30 other major tech companies had regular meetings with a cluster of national security agencies, including the ODNI, the National Security Division of the Justice Department, and both the FBI and the DHS (see #s 2 and 3 on this list). On at least a few occasions intelligence agencies like the CIA asked to attend these meetings. The participants would be sent a general agenda in advance:

The arrangements surrounding these meetings were unusual. Unlike other standing get-togethers involving government departments or agencies (Twitter met with the Defense Department regularly, for instance), the time and date for the “USG” industry meeting was usually arranged by a representative of one of the big tech players, often a Facebook executive.

But the agenda appeared in most cases to have been set by federal agencies. Why?

Only in a few cases, like the note below from August 2020, did we find communications that spelled out exactly which agencies were in attendance:

Why does this matter? When Alex Jones was removed almost simultaneously by Apple, Spotify, YouTube, Twitter, and PayPal in the summer of 2018, figures like Apple CEO Tim Cook hastened to say, “I’ve never even had a conversation about [Alex Jones] with any other tech companies. We make our decisions independently.” Virtually every media outlet stressed it was an “independent” decision.

But as one prominent law professor explained to me, removals of this type could only work only if all of the companies censored essentially the same material at once. But “they cannot coordinate without running into antitrust problems. So they are dependent on government or government-supported or aligned private entities to do the coordination for them.”

Figuring out who coordinated tech industry get-togethers on content is crucial to resolving questions about potential violations of both the First Amendment and antitrust law. It’s bad if the government is broadly guiding censorship decisions, but also a very serious problem if it’s merely providing a forum for companies to do it on their own.

Either way, getting to the bottom of exactly what was discussed at these meetings would be one of the first steps I’d consider, if I were diving into a thicket of documentation from the government side, and the Twitter Files can help with dates, times, and agendas.

The Foreign Influence Task Force (FITF)

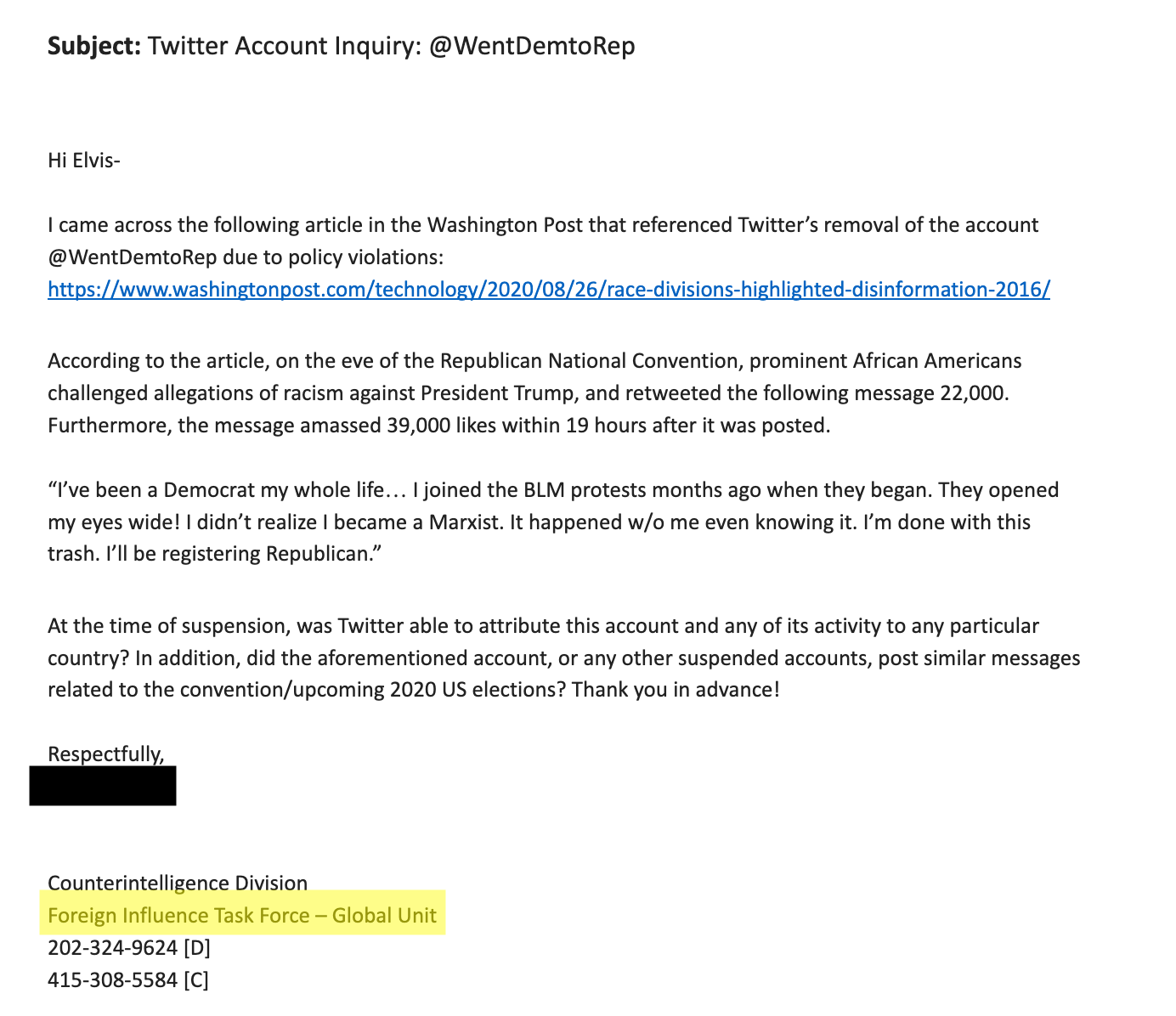

The Countering Foreign Influence Task Force (CFITF) The FBI’s FITF and the Department of Homeland Security’s CFITF were organizations whose mandate to prevent “foreign” influence didn’t prevent deep and abiding interest in domestic speech. An FITF Unit Chief peppered Twitter with questions about social media trends during the George Floyd protests, while CFITF forwarded requests from state officials, often on questions with no “foreign” connection, like retweets of Donald Trump claims about electoral fraud, or complaints about an American parody site critical of Ukraine. Both organizations occasionally asked Twitter to look into tweets certain FBI or DHS officials felt were fishy. Here, a query was passed from FITF in Washington to the San Francisco field office; the request to ask Twitter to check out “WentDemtoRep” didn’t even need articulating:

The FITF/CFITF appeared to be a primary means by which federal law enforcement exerted pressure on private speech platforms, usually by asserting a theoretical (at best) foreign connection. We compiled lists of names and email addresses of of FITF/CFITF officials, along with dates of requests, as well as attachments containing lists of suspect accounts. How many employees were assigned to this work? At whose behest were these offices created? Who decided what reports to pass on to the private sector? All unknowns, still.

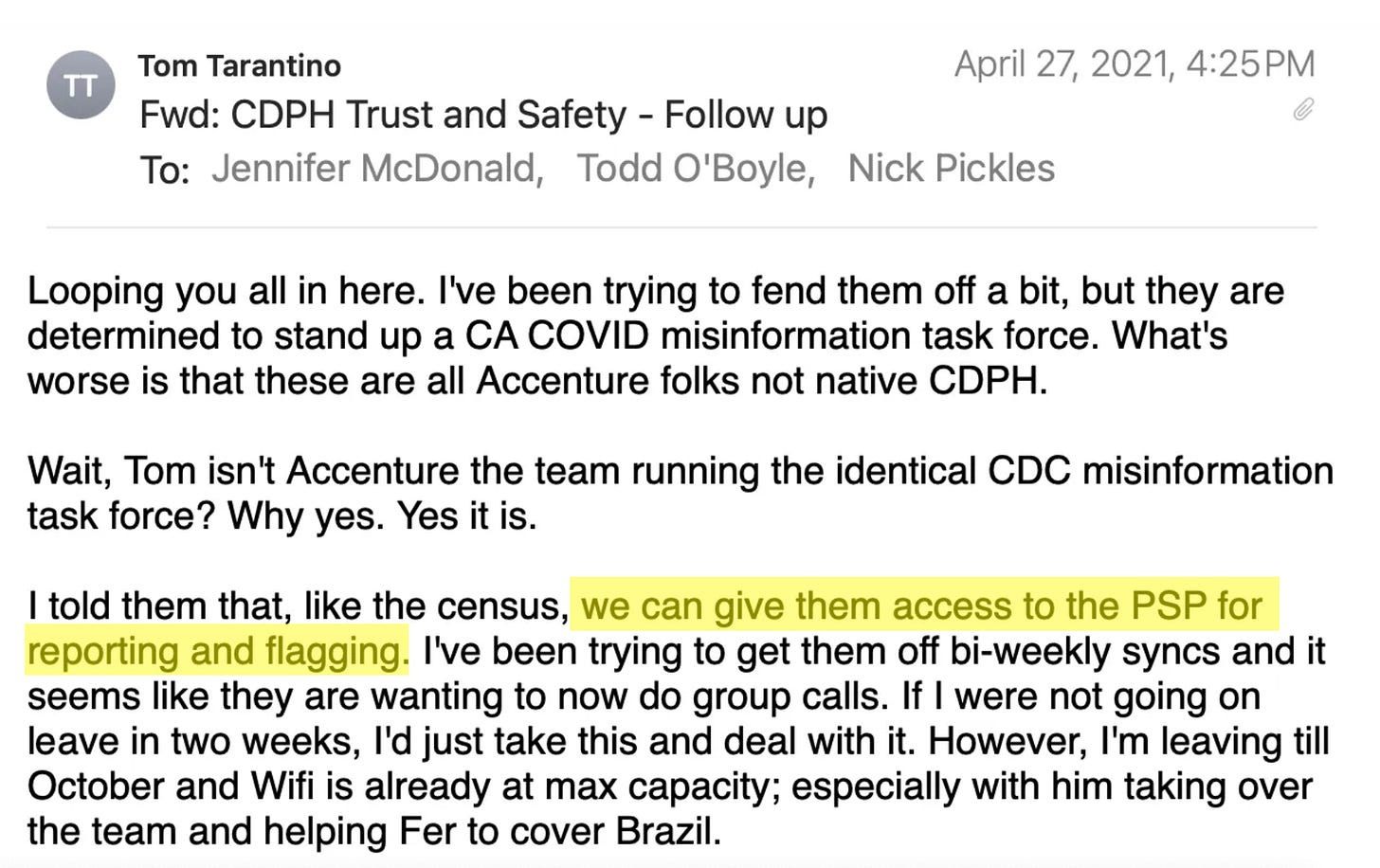

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) During the pandemic multiple state agencies sought access to Twitter executives. Each had to apply to be enrolled in Twitter’s aforementioned Partner Support Portal, to which numerous communications showed the CDC had early access. CDC guidance was essential in decisions to remove tweets by figures like Harvard’s Dr. Martin Kulldorff, and it guided the recommendations of quasi-private organizations like Stanford’s Virality Project.

But, we couldn’t see what was inside the PSP communications. While it appears some CDC guidance made its way to platform C-suite discussions by way of the White House (some of the Twitter Files as well as the exhibits in Murthy v. Missouri show this), the direct “reporting and flagging” recommendations from the CDC would tell us a lot about whether health agencies were used to target legitimate speech imporoperly, especially about Covid-19:

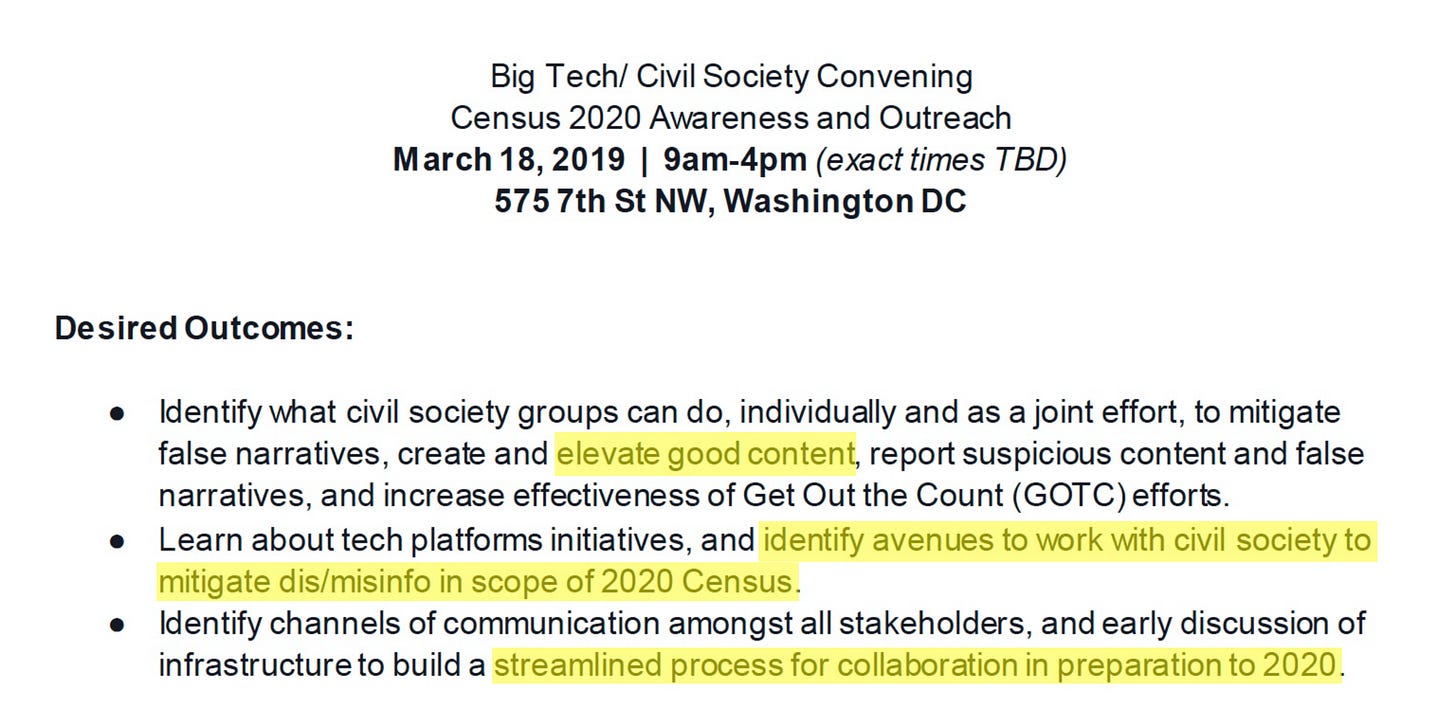

U.S. Census Bureau/Department of Commerce. The Census Bureau had to be near the top of the list of agencies we didn’t expect to find tied to formal “anti-misinformation” efforts. But the Bureau was yet another federal agency that organized industry actors to meetings to discuss how to “mitigate mis/disinfo” and “elevate good content.” It was also one of many federal agencies that stressed building a cooperative mechanism ahead of the 2020 elections. What files exist internally on these subjects?

The Department of Justice. Twitter executives seemed close to the DOJ/FBI, and there were several instances of Justice officials appearing to tip off Twitter to developments that could hurt business. In one email in 2021, Twitter officials learned the outgoing Trump administration might not follow through on implied threat to section 230 protections. Executives mentioned that the DOJ was coordinating a “State Attorneys General Working Group” that would “look at a number of things like algorithms to suppress content.” Ostensibly this was about “deceptive practices,” but any government-instigated idea that would employ algorithmic suppression would definitely warrant a look. Did the DOJ follow through on this?

The DOJ (in particular the National Security Division) was a ubiquitous character in the Twitter Files and also occasionally asked the company’s assistance with “disruptions” of targeted businesses and individuals, and other questionable support.

The Global Engagement Center. The State Department office for countering “foreign propaganda” played a central role in Twitter Files investigations, sending reports on disfavored accounts and supporting the infamous Election Integrity Partnership before the 2020 presidential race. Especially with word that the agency may not be shuttering as previously reported, it’s vital to know more about the State Department’s ambitions with regard to domestic speech. Why would the GEC for instance care that a schematic diagram of American public and private speech-policing organizations may have been shown at a Mike Lindell-funded conference? Note how one Twitter official explains to another that “we work with them on foreign disinformation,” then passes on a bulletin that has nothing to do with any foreign country:

I could go on. Twitter’s “Trust and Safety” executives attended countless conferences at which officials from the White House, the DoD, DOJ, and other agencies would attend, in addition to European or Australian bodies interested in establishing a tighter global “accountability framework.” Clearly there were regular transatlantic discussions geared toward setting up something like a single transatlantic clearing-house on “disinformation,” but we were never able to find the right point of entry. Was it NATO/STRATCOM? Were academic conferences the key? What about a think-tank that conducted “tabletop” exercises to help journalists plan for a “hack and leak” story on Hunter Biden and Burisma, but also issued ambitious recommendations for global reforms?

Tackling such unanswered questions would help us understand how close we came to the U.S. implementing something like Europe’s Digital Services Act, which would have effectively wiped out the First Amendment. There are ways this could have been accomplished without legislation, without the public even being aware of it.

To this end, there’s traffic in the Twitter Files about agencies ranging from the NSA to other DOD groups to the U.S. Surgeon General’s Office to the National Science Foundation and beyond. For every government office, there are a dozen or more NGOs or federal contractors with whom Twitter worked, often using euphemisms like “information sharing” and “building trusted relationships.” Investigations again stalled from the Twitter side because of a lack of visibility into government operations.

The Twitter Files as a pop-culture phenomenon were useful in helping shine a light on a few big problems that previously had been denied, by both the state and the private sector. But making noise through journalism only goes so far. Investigators could do more with this material, to help solve deeper mysteries. I think I speak for most Racket readers in saying, I hope someone gives it a try.

More proof that subscribing to Matt is the best investment I make on substack.

Thank you for continuing to reveal the corruption of our government and big tech, Matt. You and the Racket News team are national treasures.