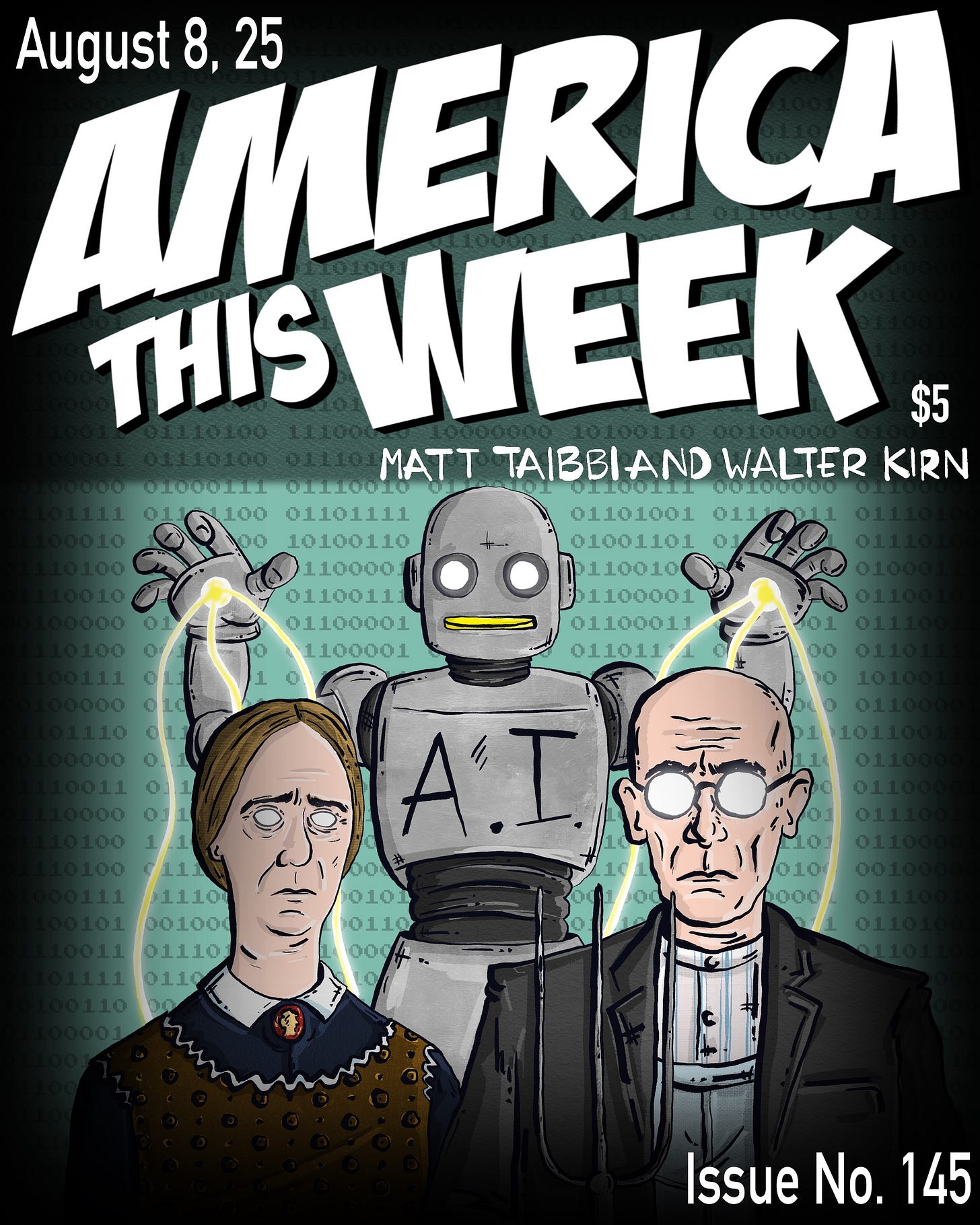

Transcript - America This Week, August 8, 2025: "The AI Invasion: Why the Media Won't Correct Itself"

When all you have to convince is a programmable AI, journalism becomes a contest of might, not right. Plus, the brutal hilarity of Voltaire's "Candide"

Matt Taibbi: All right. Welcome to America This Week. I’m Matt Taibbi.

Walter Kirn: And I’m Walter Kirn.

Matt Taibbi: Walter, I want to start the show. I want to get deep with you about something-

Walter Kirn: Okay, good.

Matt Taibbi: ... quick. I want to ask you a rhetorical question.

Walter Kirn: Okay.

Matt Taibbi: Actually, it’s not even a rhetorical question, it’s a philosophical question. Do you view fiction writing, what you do for a living, on some level as a quest for truth? In other words, are you trying to write something that’s true the way Hemingway described it, like one true sentence. Hunter Thompson once said, “The best fiction is truer than any journalism.” Do you view what you do as a quest to find something that’s eternal and true?

Walter Kirn: Well, after you are forcing me to contradict both Hunter Thompson and Hemingway, if I say, no-

Matt Taibbi: No, it’s okay. No, I’m interested.

Walter Kirn: But the answer is yes. I’m not kissing Hunter’s ass or coming after Hemingway, but the answer is, of course, yes. I am after that kind of truth that people feel when they close a book or they finish a chapter and they go, “Oh my God, that cut deep. Oh, I just heard the bell ring in my soul.” That kind of truth.

Matt Taibbi: Right. And I think this is something that’s consistent across all genres of art. Comedy. Seinfeld talks about how the audience’s reaction is true. You can’t fake it. It’s either funny or not. Certainly, for most of my career, I view journalism, yeah, it’s kind of a junior league version of what art is, right? It’s a quest for truth. It’s not as highfalutin and exalted as fiction writing or comedy or any of those things, but it comes close, right? You’re trying to be accurate. You’re trying to get to something that’s lasting.

Walter Kirn: I think especially journalism, which synthesizes smaller stories into a bigger story, getting down the record of what happened that day and what spokesman said what, and the numbers that come out of an accident or something, that’s factuality. But journalism, I think, does seek truth when it put together stories and create a sense of what’s really happening and gets into human motivations and things like that.

Matt Taibbi: So just, again, to go to Hunter because he’s the American icon of our business. Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ‘72, that’s a very true book about what campaigning is like.

Walter Kirn: Right.

Matt Taibbi: You know what I mean? The sights, sounds, smells, emotions, all those things, I think they were very lasting for a long while.

Walter Kirn: Well, and I’ll say one more thing. Fiction often misses the truth because fiction gets caught up in tropes and conventions very easily, and it loses touch with reality. And one of the things that I think great journalism like Hunter’s does is it refreshes our ability to see reality. We really had political campaigns in fiction that didn’t resemble real ones for a long time. We had the conventions, we had the whistle stops, or a ton rhetorical exaggerations of the candidates and the pom-pom girls and so on, but he really got the tedium of it and the weirdness of it and so on.

Matt Taibbi: Yeah, the weird adrenaline rushes in between all the dead spots, right?

Walter Kirn: Yes.

Matt Taibbi: The weird fascinations you have with candidates, the disillusionment, all that stuff, right? And conversely, that’s why I don’t love books by people like Henry James. Things are too polished. They’re too perfect. It doesn’t feel like reality to me. It’s not weird enough. There’s something missing.

Anyway, I say all this as a preface to, what if suddenly the game changed? We all, for all of our lives, imagine, for instance, journalism to be about trying to find answers to underlying questions and get things right. What if suddenly it wasn’t about that anymore? What if the standard was to have enough quantitative convincing power to force a version of reality onto people that isn’t real?

Walter Kirn: Well, Matt, I think our audience has waited for this moment because whether you know it or not, I think you’re reaching a conclusion that underlines and underlies a lot of my assumptions for a long time here on these big mega stories. Because you are so dogged and single-minded in your pursuit of the truth, I think you’ve lost touch sometimes with how badly the rest of the field does it, and how completely changed their priorities have been. You continue to see the best in them. I, of course, look for the worst, first of all, never wanting to be disappointed.

It’s because I’m a lightweight. I always want the bad news first so I can get used to it. And you’re absolutely right, impact, leverage, the projection of pure brute power, getting people to do things. When we remember that Catherine Maher speech that she gave about there not being truth because she said, “We want to get you to do things.” And that’s, I’m afraid, what so much journalism has become, and I think I know where you’re going, it’s where it might go in a turbocharged fashion soon.

Matt Taibbi: Yeah. And I think we’re in that moment of acceleration.

Walter Kirn: Yes.

Matt Taibbi: And what are we talking about? We’re talking about AI, but it’s AI in addition to all the things that Walter and I have been talking about for years is about anti-disinformation and other things. Essentially, AI is about to become the dominant factor in information and how it’s related not just in journalism, but in academia and all kinds of other things. And we’re going to see some of the stories that have come out just in the last few weeks.

Journalists are now realizing that you don’t have to apologize to audiences for getting things wrong anymore because it’s not the human audience that really matters, it’s the AI audience, it’s the algorithms, it’s the platforms, and it’s how they weigh how authoritative you are, and they will continue to present a wrong version of reality, if so programmed, right? Am I getting that wrong, or is there a better way to put this?

Walter Kirn: No, I think it’s a great way to put it. I would just footnote what you said. Their authority is something that they carry from the pre-AI age into this one. In other words, the paradox of this is that the authority is not based on how often you told the truth recently, but how much of a reputation you developed in the old world.

In a strange way, you can be a liar now if you developed a reputation for truth in the past because your statements are favored algorithmically by the AI. A lot of these places are harvesting the fruits of their past integrity, which gave them the reputation or the market share or whatever it might be. The pure number of hits that caused the AI to favor their input.

Matt Taibbi: Awards. Yeah.

Walter Kirn: Awards and so on. But now they can abuse it because they won’t be questioned. You see, when we talk about truth, it’s who determines it that I think is at the root, and you just brought this up. In the old days, truth meant does it register in the reader’s mind as logical in accord with their own experience or in accord with other places that have informed them? Now, we’re not making the truth judgment, in fact, it’s not being made at all.

What’s being made is a kind of search engine style, prioritizing, and it’s a mathematical judgment, not a judgment of correspondence between elements that says, “Does this correspond to what I know, what I’ve read, and what I’ve learned?” And does it come from a journalist who has the authority? You see, Matt, if something comes from you, I’m more likely to believe it’s the truth because you’ve made that a priority in your writing, and you’ve corrected yourself and you’ve beaten yourself up when you’ve gotten things wrong, but when it comes from Grok, or whatever, ChatGPT, it has no presumption of integrity. It’s simply the result of a mathematical equation.

Matt Taibbi: Right. And this is the part that has stumped me and a lot of old-timers in the business. So beginning, I would say, with the WMD thing, but really taking off with the Russiagate story, the phenomenon of being caught in a lie publicly, having it written about at length, having it out there, and yet not making a correction. That was something that’s kind of new. If you got caught previously, the rest of the business piled on to you, and you would have to issue a correction. And sometimes it was career-ending and it was painful, and sometimes they did it selectively, like to Judith Miller and not to others in the WMD story. What happened with this Russia story, and we’re not going to spend all our time in Russiagate today.

We’re going to talk about AI more, I would say. But a lot of the people in the business who grew up with this other standard are looking at this and saying, “Well, how can they keep saying this one thing? If these other facts have surfaced, then how can you keep saying that?” And it seems maddening, but the reason is because that’s how the algorithms work. Even before we got to AI, Google, in 2017, right as this story was taking off, they reinstituted something called Project Owl or they instituted something called Project Owl. And this was in part incidentally in reaction to complaints that conspiracy theories had surfaced too much in the 2016 campaign, allowing disinformation to reach, say, Trump voters.