The Luke Harding Experiment

Will future reporters refer to unsourced exposes as "Hardings"? On the recent second flight of the Guardian's one-man journalistic Hindenburg

Eight days ago, on July 15th, The Guardian published an apparent bombshell by reporting curiosity Luke Harding and two other writers, entitled, “Kremlin papers appear to show Putin’s plot to put Trump in White House.”

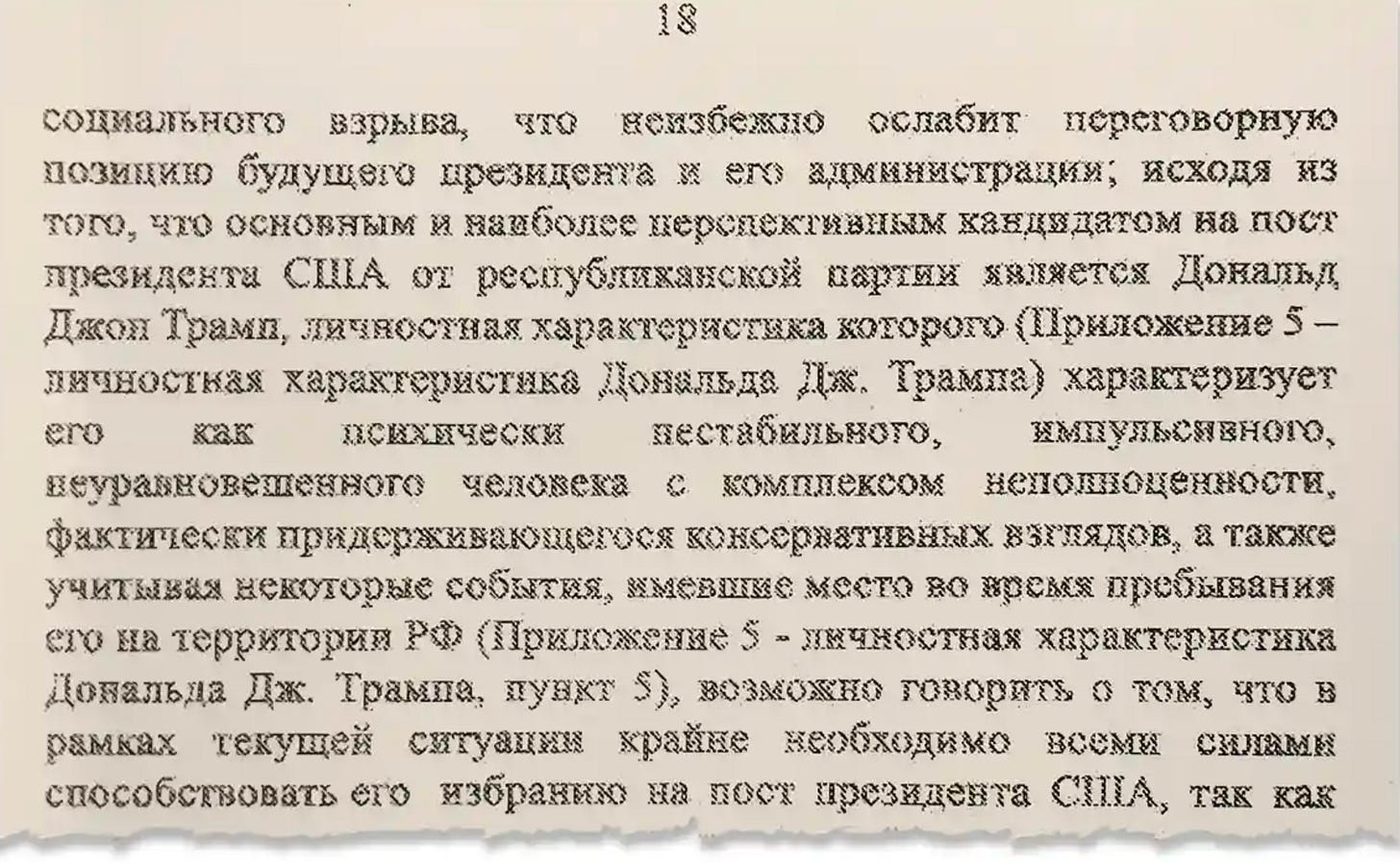

The paper claimed to have gotten hold of “leaked Kremlin documents” from January 2016, showing a secret plot by Russia to use “all possible force” to help elect “the most promising candidate,” Donald Trump, in order to bring about the “destabilization of the US’s sociopolitical system.”

The article featured a snippet of the alleged document that purported to show Russian officials copping to the entire Russiagate narrative in a single sentence, even adding what the Guardian called “apparent confirmation” that the Kremlin possessed compromising knowledge about “certain events” involving Trump on Russian territory:

It’s almost impossible to describe how low you have to have sunk for the American media to walk away from a story like this, in a still-vibrant environment of Trump-Russia mania. It’s like being unable to give away video game credits at Chuck E Cheese. Yet the explosive report was picked up by exactly zero American news agencies. The silence was so deafening, the rival Daily Mail wrote an article gloating about it.

A week after the expose’s publication, the Washington Post — maybe the most enthusiastic print trafficker of McCarthyite paranoia in recent years and home to many of the biggest actualintelligenceleaks through the Trump-Russia affair — finally addressed the “leaked Kremlin documents.” The piece by Phillip Bump tried to take the Harding revelations seriously, but couldn’t, saying the article “reads like one of those viral Twitter threads from a guy with 4.4 million followers whose bio describes him as ‘resister-in-chief.’”

Ouch. Why so harsh? The Post mentions the reason: the Guardian author, Harding, also wrote one of the most infamous uncorroborated “bombshells” of this era, a November 27, 2018 report alleging Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort met with Julian Assange in the Ecuadorian embassy.

This would-be smoking gun proof of collusion took the news world by storm for days, as the Trump-mad press went blind with eagerness, like high school boys seeing their first boobs. Poor Ari Melber of MSNBC would probably like this broadcast back, where he gushed that the Guardian report might be the “key to collusion,” noting:

Sources tell the Guardian the key meeting lasted 40 minutes, and they have details, like that [Manafort] was dressed in chinos, cardigan, and a light shirt… Now, tonight, Paul Manafort is denying this story. I can report that. I can also report that Paul Manafort is a serial liar.

This wasn’t just a bombshell, it was a bombshell with details. Who could make up chinos? “If it looks like collusion, meets like collusion, and acts like collusion, it probably is collusion,” agreed congresswoman Jackie Speier.

Slowly, however, the minor issue of there being no record of any meeting between Manafort and the most surveilled person on earth began to raise concerns among America’s press wizards that the story might be on something less than solid ground. The Washington Post’s polite formulation was that Harding’s story was a bomb that “still hasn’t detonated.”

The Guardian compounded the comedy. In the face of intense public criticism over the absence of evidence for such a major assertion, the paper essentially made one change. The headline, “Manafort held secret talks with Assange in Ecuadorian embassy” became “Manafort held secret talks with Assange in Ecuadorian embassy, sources say.”

Needless to say, the qualifier didn’t exactly address concerns. This time around, the Guardian did their touching-up in advance, applying in bulk phrases like “what are assessed to be leaked Kremlin documents,” “the papers suggest,” “appearing to bear Putin’s signature,” “seem to represent,” “appear to be genuine,” “apparent confirmation,” etc. Despite these fine efforts, the silence over the new piece shows unchanged judgment on the Manafort-Assange affair, with editors essentially announcing an unwillingness to be hoaxed a second time.

In response, Harding a few days ago tweeted a link to a YouTube interview with former KGB agent and co-author of American Kompromat, Yuri Shvets:

This is an excerpt from today’s subscriber-only post. To read the entire article and get full access to the archives, you can subscribe for $5 a month or $50 a year.