The Death of Humor

Review of "Killer Cartoons," edited by David Wallis, and "White," by Bret Easton Ellis

Review of Killer Cartoons, edited by David Wallis, and White, by Bret Easton Ellis

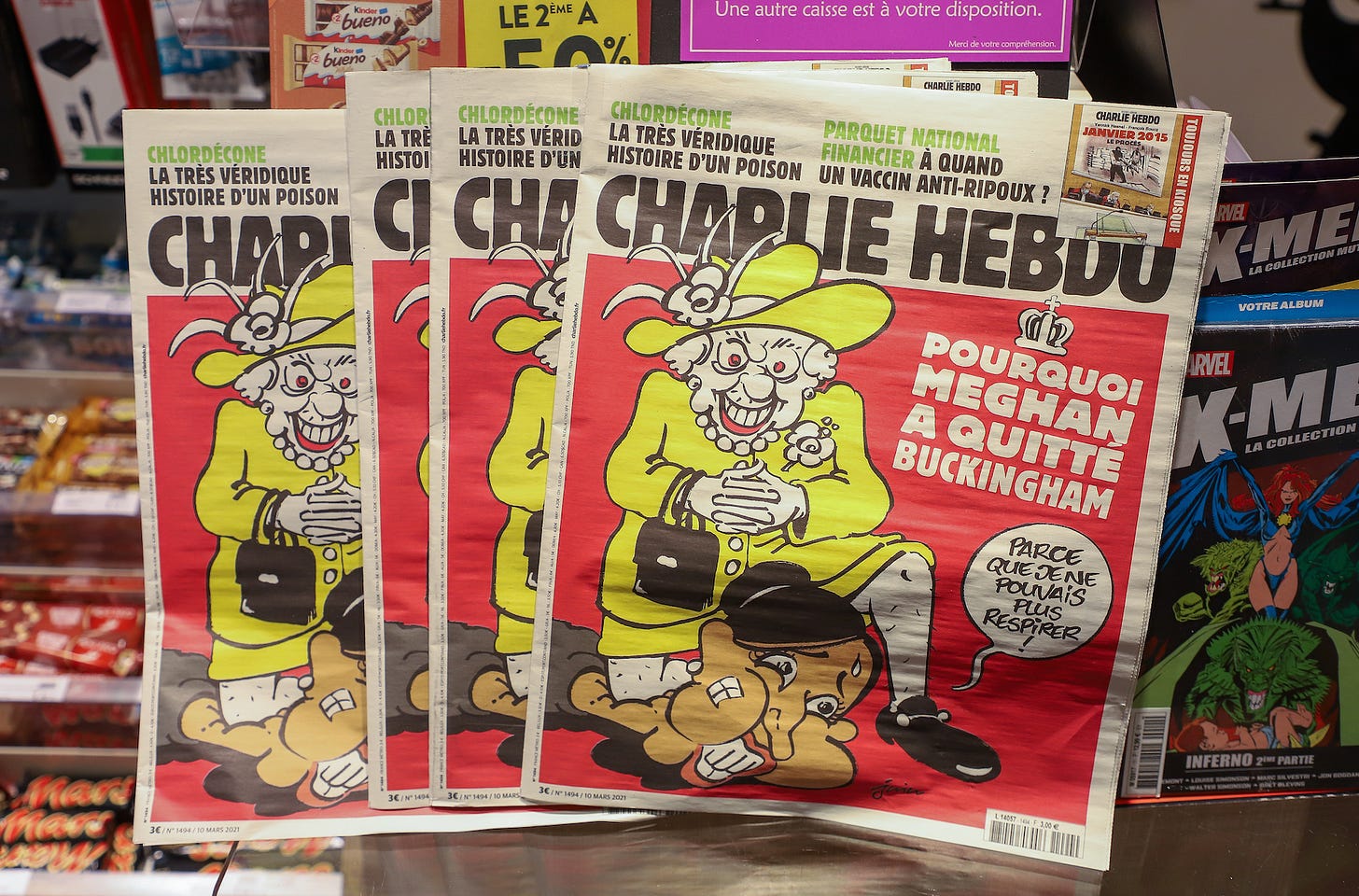

The French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo won the condemnation of the whole world again, with the following cover:

Reactions ranged from “abhorrent” to “hateful” to “wrong on every level,” with many offering versions of the now-mandatory observation that the magazine is not only bad now, but “has always been disgusting.”

This cover is probably an 8 or 9 on the offensiveness scale, and I laughed. It goes after everyone: Queen Elizabeth, depicted as a more deranged version of Derek Chauvin (the stubby leg hairs are a nice touch); Meghan Markle, the princess living in incomparable luxury whose victimhood has become a global pop-culture fixation; and, most of all, the inevitable chorus of outraged commentators who’ll insist they “enjoy good satire as much as the next person” but just can’t abide this particular effort that “goes too far,” it being just a coincidence that none of these people have laughed since grade school and don’t miss it.

Six years ago, after terrorists killed 10 people at Hebdo’s Paris offices in a brutal gun attack, the paper’s writers, editors, and cartoonists were initially celebrated worldwide as martyrs to the cause of free speech and democratic values. In France alone on January 11, 2015, over 3 million people marched in a show of solidarity with the victims, who’d been killed for drawing pictures of the Prophet Muhammad. Protesters also marched in defiance of those who would shoot people for drawing cartoons, especially since this particular group of killers also fatally shot four people at a kosher supermarket in an anti-Semitic attack. For about five minutes, Je Suis Charlie was a rallying cry around the world.

In an early preview of the West’s growing sympathy for eliminating heretics, cracks quickly appeared in the post-massacre defense of Charlie Hebdo. Pope Francis said that if someone “says a curse word against my mother, he can expect a punch.” Bill Donohoe, head of the American Catholic League, wrote, “Muslims are right to be angry,” and said of Hebdo editor Stephane Charbonnier, “Had he not been so narcissistic, he may still be alive.” New York Times columnist and noted humor expert David Brooks wrote an essay, “I Am Not Charlie Hebdo,” arguing that although “it’s almost always wrong to try to suppress speech,” these French miscreants should be excluded from polite society, and consigned to the “kids’ table,” along with Bill Maher and Ann Coulter.

Humor is dying all over, for obvious reasons. All comedy is subversive and authoritarianism is the fashion. Comics exist to keep us from taking ourselves too seriously, and we live in an age when people believe they have a constitutional right to be taken seriously, even if — especially if — they’re idiots, repeating thoughts they only just heard for the first time minutes ago. Because humor deflates stupid ideas, humorists are denounced in all cultures that worship stupid ideas, like Spain under the Inquisition, Afghanistan under the Taliban, or today’s United States.

During the Trump era, there was a steep decline of jokes overall, but mockery of a president who’d say things like, “My two greatest assets have been mental stability and being, like, really smart” rose to unprecedented levels. It was not only okay to laugh at Trump, it was mandatory, and the more tasteless the imagery, the better: Trump gay with Putin, Trump gay with the Klan, Trump with micropenis, Trump’s face as mosaic of 500 dicks, Trump as a blind man led by a seeing-eye dog who has the face of Benjamin Netanyahu and a Star of David hanging off his collar, Trump with a pen up his ass, Trump with tiny penis again.

Pundits guffawed even more when someone threatened to sue artist Illma Gore for her “Trump’s tiny weiner” pastel, displayed at the Maddox Gallery in London. "It is my art and I stand by it,” Gore said. “Plus anyone who is afraid of a fictional penis is not scary to me.”

People cheered, because of course: anyone who even threatens to hire a lawyer to denounce a drawing has already lost. Cartoonists in this sense had no better friend than Trump, who constantly tried to block unfriendly renderings, including a Nick Anderson cartoon showing him and his followers drinking bleach as a Covid-19 cure (the Trump campaign reportedly called Anderson’s drawing of MAGA hats a trademark infringement). A lot of the anti-Trump cartoons were neither all that creative nor funny — if “He’s gay and has a little dick!” is the best you can do with that politician, you probably need a new line of work — and were only rescued by Trump’s preposterous efforts to defend his dignity. You can’t police a person’s private instinct to laugh, and there’s nothing funnier than watching someone try, especially if that person is already a sort-of billionaire and the president.

For all that, most of the jokes of the Trump era fell flat, precisely because they were obligatory. Modern humorists must laugh at bad people: racists, sexists, conspiracy theorists, Trump, anyone but themselves or the audience. There were artists who made great humor out of Trump. “Mr. Garrison snorts amyl nitrate while raping Trump to death” stood out, while Anthony Atamaniuk’s impersonations worked because he genuinely tried to connect with the Trump in all of us, asking, “Where’s the Trump part of my psyche?” But most Trump humor was just DNC talking points in sketch form, about as funny as WWII caricatures of Tojo or Hitler.

Saturday Night Live even commemorated the release of the Mueller report and the death of the collusion theory not by making fun of themselves, or the thousands of pundits, politicians, and other public figures who spent three years insisting it was true, but by doing yet another “Shirtless Putin” skit, with mournful Putin declaring, “I am still powerful guy, even if Trump doesn’t work for me!” I defy anyone to watch this and declare it was written by a comedian, and not someone like David Brock, or an Adam Schiff intern:

Humorists once made their livings airing out society’s forbidden thoughts, back when it was understood that a) we all had them and b) the things we suppressed and made us the most anxious also tended to be the things that made us laugh the most. Which brings us to Killed Cartoons: Casualties From the War on Free Expression.

Killed Cartoons is a history of a time when editors and cartoonists alike were trying to toe the line between what people found funny in private, and what was considered acceptable fodder for public ridicule. We’re way past that now, when we’re not supposed to have unwholesome thoughts either in public or in private. In fact, the whole concept of private thoughts has become infamous. Why does anyone need private opinions, in a society where the right opinions on every question are known, and should be safe to say publicly?

This is an excerpt from today’s subscriber-only post. To read the entire article and get full access to the archives, you can subscribe for $5 a month or $50 a year.