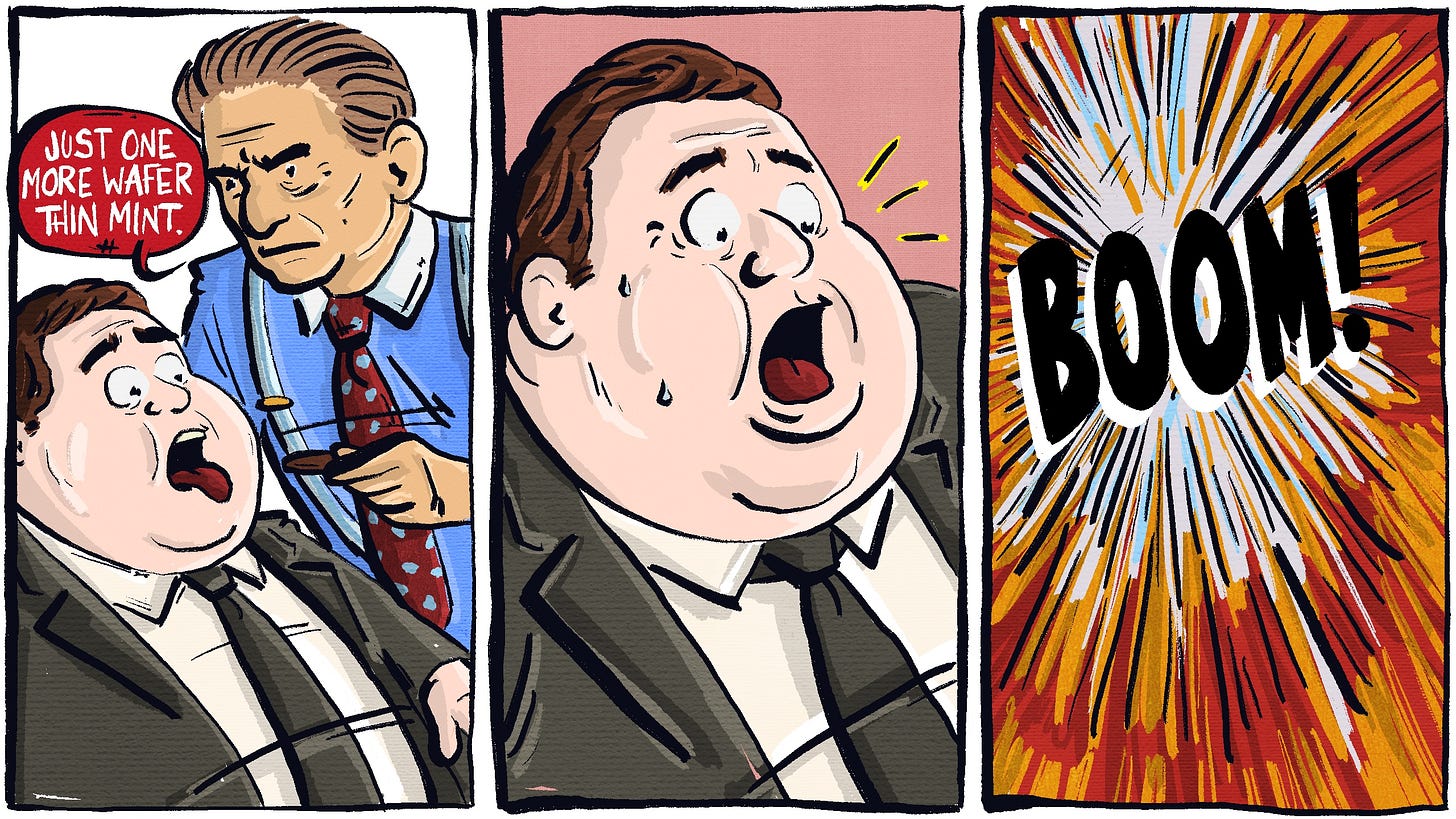

One More Wafer Thin Mint?

Private Market business is bloated with expensive debt that many can't afford, so naturally Private Credit's solution is to add more

Back in the “good old days” of subprime mortgage-mania, the business of making loans and securitizing them took on the appearance of the proverbial tail wagging the dog. The participants in the business of making the loans, securitizing them, selling them and managing them could not care less who was actually getting the loan. There seemed to be an endless supply of global capital that “needed” to be put to work in subprime. Wall Street was making billions and the only thing that mattered was creating a loan, no matter how ridiculous, to feed the subprime structured-product market.

We know how all that turned out.

I get the strong feeling this is what has been happening in the Private Market (Private Equity and Private Credit) investment sector.

Let’s focus on Private Credit, a rapidly growing asset class.

Private Credit (PC) represents direct lending to private companies, many of whom are owned in PE portfolios from Non-Bank Lenders (NBLs). Many of the same investment management companies who are big players in Private Equity (PE), such as Blackstone, Apollo, Ares and KKR are also NBL managers of PC funds. These managers, as well as many others, have been rapidly raising capital to grow their PC funds as investors such as life insurers, pension funds and foreign sovereign wealth funds clamor to invest heavily. Many of the nation’s large banks have been rapidly increasing their lending to PC funds. Morgan Stanley reported last year that PC had a market size of approximately $1.5 trillion, with the potential to be $2.8 trillion by 2028.

Private credit can very well be a good thing by providing liquidity to underbanked businesses. But with its rapid growth, has PC become just another way to feed Wall Street’s Private Market deal beast and overload the economy with debt?

Last week Bloomberg News reported:

Bankruptcies by mid-sized private US companies hit their highest level since 2010 last year as high interest rates and costs squeezed profits… and so far 2025 looks poised for another record, according to a report from Marblegate Asset Management and RapidRatings. Expensive debt and higher costs are leaving firms barely able to cover their debt payments and more than a fifth of analyzed companies in 2024 had interest coverage ratios of less than 1, meaning that they’re unable to generate enough earnings to cover interest payments, the firms said in the report. The average interest coverage ratio was 1.26 times last year, as shrinking earnings, more leverage and higher rates have “eroded solvency” for many companies, they said.

The Marblegate report “analyzed more than 1,200 private companies with revenue between $100 million and $750 million, and compared them to about 1,700 publicly traded companies with revenue of $750 million or less in the Russell 3000. The private companies have seen a measure of their income — earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization — fall 23% since 2019. At larger public corporations, EBITDA rose 16% over the same period.”

The trend does not seem to be our friend here with regard to loading more private companies with more debt. Yet with all the capital pouring into the PC sector, we seem to be doubling down on it. It is important to remember that we are seeing the deterioration noted by Marblegate while the economy is doing reasonably well. What happens in a recession, or worse, what happens if we have a recession combined with inflation — stagflation?

According to a report from the Federal Reserve this past May about the nation’s banking sector,

Committed credit lines by the largest U.S. banks to private credit vehicles (PD funds and BDCs) have increased significantly over the past five years (about 145 percent, equivalently to an annualized growth rate of about 19.5 percent), reaching about $95 billion as of 2024-Q4.

In 2025 we can see that banks have continued to increase their exposure to PC funds. For example, this past February JP Morgan announced they were increasing their $10 billion commitment to PC to $50 billion.

The Fed’s report went on to say,

The bulk of bank loans to NBFIs (non-bank financial institutions) are rated investment grade, exhibit very low delinquency rates and tend to be of shorter maturity than loans to nonfinancial corporations.

Remember how we relied on our great ratings agencies, S&P and Moody’s, for their discernment of subprime securities?

The report continued (emphasis mine):

“While immediate risks from private credit vehicles appear limited due to their moderate use of leverage and long-term capital lockups, the lack of transparency and understanding of the interconnectedness between private credit and the rest of the financial system makes it difficult to assess the implications for systemic vulnerabilities.”

That last bit doesn’t exactly give a warm and fuzzy feeling.

Then there’s JP Morgan struggling mightily to create a secondary trading market for PC loans, Bloomberg News reported last month:

Private credit managers have a message for the JPMorgan Chase traders who have been trying to establish a secondary market for the industry: no thanks.

Bloomberg reported that the PC managers have a strong motivation to say no to JP’s efforts because of “the fear that if JPMorgan, or any of the other banks following in its footsteps, is successful in creating a vibrant trading market for the loans, it could shatter the perception—or mirage, as critics would argue—of price stability that they’ve spent years selling to investors. The value of the loans, the pitch goes, won't ever get whipsawed around, and dragged down, by the vagaries of the broader markets because they are privately held assets. But if they trade regularly, price levels get marked, day after day, and private credit suddenly doesn't look all that different than its public market counterparts.”

I guess the “vagaries of the broader markets” include fundamental analyses that show a particular borrower’s or an entire industry’s ability to service their debt is quickly deteriorating? As an investor, that is something they might want to know, right?

Is all of this really necessary or is it just another gigantic payday for Wall Street, where if it all blows up and tanks the nation, they just walk away with the billions they already made and move on to the next big thing?

Do we really need “one more wafer-thin mint?”

My favorite part of this whole thing comes after the securitization scheme blows up and the government (i.e. taxpayers) starts bailing out the banks that sold these bundles of bad debt to investors. Then the regulators meet and congress issues a 200 page report where they declare the resulting disaster was a big surprise that no one saw coming.

Private credit has its uses, particularly for mid-sized companies with limited leveragable working capital and due to market inefficiencies caused by post Dodd-Frank bank regulations (ie banks can’t lend as much to leveraged entities). The real business case for it, though, was the long-gone zero interest rate and QE era (now replaced by inflation and “normal” interest rates).

Unfortunately, some of the recent surge has been used to refinance maturing bank loans from the COVID bubble (zero rate) era. These companies and real estate projects are in deteriorating condition financially and likely could not attract bank credit without restructuring or a credit event. We certainly hope the sponsors don’t have a “I’ll lend to your bad credit if you lend to mine” mentality. This has been supposed, but seems unlikely to me (at least not so baldly) given the deep pockets, on-call legal teams and jury-friendly identities (eg teachers’ pension funds) of their limited partner investors. If things go south, lawsuits and discovery and prosecution will follow.

I love your anecdote about the sponsors saying “no thanks” to transparent secondary markets. That would kill the bogus sharpe ratios of the whole sector.

Famous last words, but I am not too worried about a PE/leveraged credit financial sector meltdown. Leverage is what kills. In the GFC it was deposit-taking banks buying “AAA” CDOs and ABS, arbitraging the inane Basel 2 capital rules and reaching for just a little bit more return in an ROA-challenged environment with compressed credit spreads, following on from Bernanke’s helicopter money.

Rich people and pension funds and endowments losing money? That shouldn’t cause massive financial contagion (though it might lead to sane repricing of risk assets generally) and cause tax hikes at the state levels. Economically would be more like the dot com crash than the GFC.

What should not happen (but probably will) is non-HNW/non-accredited retail investors being legally offered a slice of these portfolios.

Given public markets are shrinking relative to private, and given all of the PE and VC types backing political parties, inviting retail investors in to hold the bag seems likely, unfortunately. Will it be any more disastrous, though, than so many retail types being 100 pct invested in the allegedly “diversified” and “broad” SP500 index which is actually like putting 40 pct of everything you own into the 7-10 biggest tech stocks of the moment?