Notes from a Recent Visit to Russia

‘That’s fighting there in the distance!’

A guest essay from friend-of-Racket and former “Moscow Times” editor Matt Bivens, who writes at The 100 Days.

A big noise was heard in the dark forest,

and a roar echoed.

All the animals ran

to the boyar, the Bear.

Large animals came.

Small ones came.

Captain wolf came,

showing his sharp wicked teeth,

and greedy eyes.Then came the beaver, that visiting merchant.

He, the beaver with the fat tail.

The noble weasel arrived.

Little princess-squirrel arrived.

Came the church clerk-fox, that treasurer.

Then the filthy peasant-rabbit,

poor rabbit, grey rabbit.

The hedgehog-tax collector came,

all huddled up, how he bristles …All to the bear then bowed,

and the bear told his story, crying:

Judge how I have been wronged!

I had an old shoe, of woven basket, torn,

for many years it lay unused.

Gray geese flew over it one day,

they took it and tore it to shreds,

then scattered the pieces in the open field.How am I to endure this bitter wrong?

Who will comfort my brave heart?

Aren’t we going to declare a war on birds?And they went to war, and went to war,

and bravely led the army.

That’s fighting there in the distance!

— from Rimsky-Korsakov’s Opera “The Tsar of Saltan”, playing this fall in St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theater

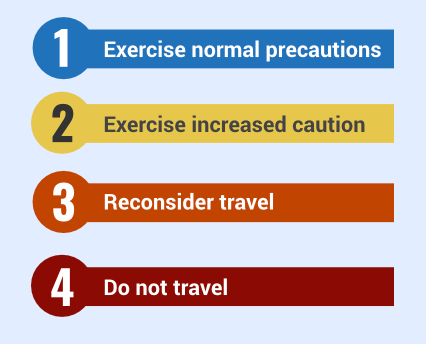

MOSCOW — The U.S. State Department said not to come here. They have a Level 4 warning against Russia travel, which is the fastest they can hyperventilate.

The warning cites free-floating peril associated with the war in not-so-distant Ukraine, “the risk of harassment or wrongful detention,” and the American government’s “limited ability to help” if you get in trouble. It concludes in bold-face:

Do not travel to Russia for any reason.

Seventeen grim-sounding bullet points follow. If you do go to Russia, State says, you should, among other things:

Prepare a will …

Discuss a plan with loved ones regarding care and custody of children, pets … funeral wishes, etc.

Leave DNA samples with your medical provider …

Make funeral arrangements!

I seriously doubt a primary care doctor would know what to do with my “pre-travel DNA samples.”

‘Do not travel to Russia for any reason.’

But Americans are traveling here every day. There are no direct flights anymore, and international sanctions have closed European and American airspace to Russian airlines. But Turkish Air among others has stepped up eagerly, and Istanbul Airport is humming with activity.

We had many reasons to travel to Russia. We needed to reconnect with friends and loved ones, and tend to various family matters. My older daughter wanted her fiancé to meet her Ukrainian-Russian grandparents, and to see the places she remembered fondly from her kindergarten days, when I worked in Russia as a journalist (before I came to my senses and went to medical school).

As a card-carrying member of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, I also wanted to meet with like-minded international physicians, to discuss, yes — nuclear war, the prevention of. And I wanted to take Russia’s temperature. It’s a place I know well but hadn’t visited for some years.

There were downsides to such a trip. One was leaving coastal Massachusetts at my favorite time of year. (Sailboat season!) Another was anxiety among family and friends, who have a media-nurtured fear of all things Russian. When I telephoned my father about our planned trip, I could hear my mother in the background call out, “Don’t get captured!”

Don’t get captured? Did we need to worry about that?

Amnesty International does say more than 20,000 ordinary Russians have been arrested and fined, and many dozens at least have received long prison terms for voicing anti-war criticism. We were just tourists visiting family, not anti-government activists. But there are no guarantees: Two years ago, a young woman from Los Angeles — a ballerina from Siberia, with American-Russian dual citizenship (just like my wife and daughters) — went for a visit home to Russia, and at passport control was interrogated about her views. Her phone was searched, and she was charged with treason (!) over a Venmo donation of $51.80 to a New York-based charity raising money for Ukraine. She was convicted, and sentenced to 12 (!) years. (She was released in April as part of a prisoner swap.)

Then there were the drone attacks. All summer, there were multiple Ukrainian-sponsored drone attacks on St. Petersburg’s Pulkovo Airport — the same airport we’d fly in and out of. One day after I left in September, Pulkovo was shut down for a full day by another large drone attack. My wife followed a few weeks later — the same day Russia shot down 46 drones headed for Moscow alone.

The only difference between these drones and terrorist car bombs are that the drones fly, and are apparently guided to target by sleeper agents of Operation Goldfish, who were trained by the CIA and spread throughout Russia.

(As an aside: imagine if American airports, residential buildings and other infrastructure were attacked by flying car bombs, month after month — even as, say, Iran bragged publicly about having secret “Operation Goldfish” sleeper agents spread through our country to guide the bombs to their targets. Would our government also start locking people up over $51 Venmo donations to the wrong people?)

This was all context for our planned trip, and it gave us pause. But by late summer, the geopolitics, which had been awful for years, looked cautiously promising. Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump had just met cordially in Alaska. It seemed a window for safe and hassle-free travel.

Since we were introducing the fiancé to Russia — and also don’t know what the future holds — we decided to treat ourselves to the full tourist experience. We would attend the Rimsky-Korsakoff Opera mentioned above, a meandering collection of Alexander Pushkin’s fairytales that revolves around the imaginary city of Tmutarakan. We’d go mushroom hunting in the woods outside of St. Petersburg, indulge in a full-day Russian banya (steam sauna) complete with the traditional massage-by-whackings-with-oak branches, ride the elegant overnight sleeping car train to Moscow, explore the Tretyakov and Hermitage museums, and have feast after feast — in fancy Russian restaurants, in Georgian restaurants, and best of all at home with the in-laws, where everyone oohed and aahed and took photos of the home-cooked Ukrainian fare, from borshch to blini.

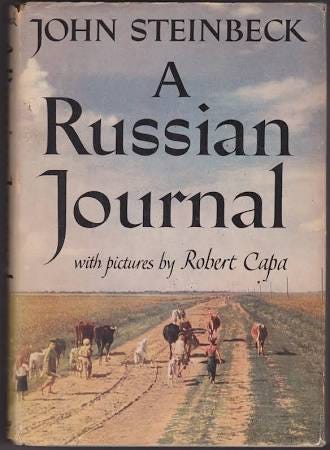

Spoiler alert, it was a wonderful trip, and no one was “captured.” I won’t bore you with most of it. Instead, I hope to reacquaint you with ordinary Russian people at this moment in time. As I pondered this idea, I remembered a 1949 classic by the novelist John Steinbeck, “A Russian Journal.” I occasionally thought of this slim book as we took our Red Square selfies, or struggled to talk politics over dinners with friends. Then, on the last day of our trip, with a pleasant jolt of recognition, I saw my own long-lost copy on my father-in-law’s bookshelf.

I took it down, and read Steinbeck’s opening account of how he and his photographer colleague Robert Capa conceived their collaboration in the late 1940s, while sitting in a New York hotel bar drinking absinthe-and-crème de menthe cocktails, and complaining about the sad state of international affairs:

Willy, the bartender, who is always sympathetic, suggested a Suissesse, a drink which Willy makes better than anybody else in the world. We were depressed, not so much by the news but by the handling of it. …

Willy set the two pale green Suissesses in front of us and we began to discuss what there was left in the world that an honest and liberal man could do. In the papers every day there were thousands of words about Russia … by people who had not been there, and whose sources were not above reproach. And it occurred to us that there were some things that nobody wrote about Russia, and they were the things that interested us most of all. What do the people wear there? What do they serve at dinner? Do they have parties? What food is there? How do they make love, and how do they die? What do they talk about?

Good questions then and today.

For anyone skeptical about a non-hostile examination of Russia amidst the carnage of Ukraine: Steinbeck the author, Willy the bartender, and many others were open to such an inquiry in 1949 — when the Soviet Union was ruled by Josef Stalin (!), had just taken over Czechoslovakia in a surprise coup, had blockaded West Berlin, and had detonated its first atomic bomb; while the Chinese Communist Party had just driven the nationalists out to Taiwan, and Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare and the U.S. war in Korea were just a year away.

For anyone still indignant, and angrily aware that far more than 1 million young men on all sides have been killed or maimed in a war Russia alone chose to launch; or, for that matter, that Russia’s recent drone attacks on the Ukrainian power grid have imposed nationwide blackouts; I can only say that I deplore the suffering everywhere — we have family on all sides of the conflict — and the war could end tomorrow if Lockheed Martin and RTX (Raytheon) America stopped fueling it and negotiated a NATO-free Ukrainian future.

Don’t Mention the War

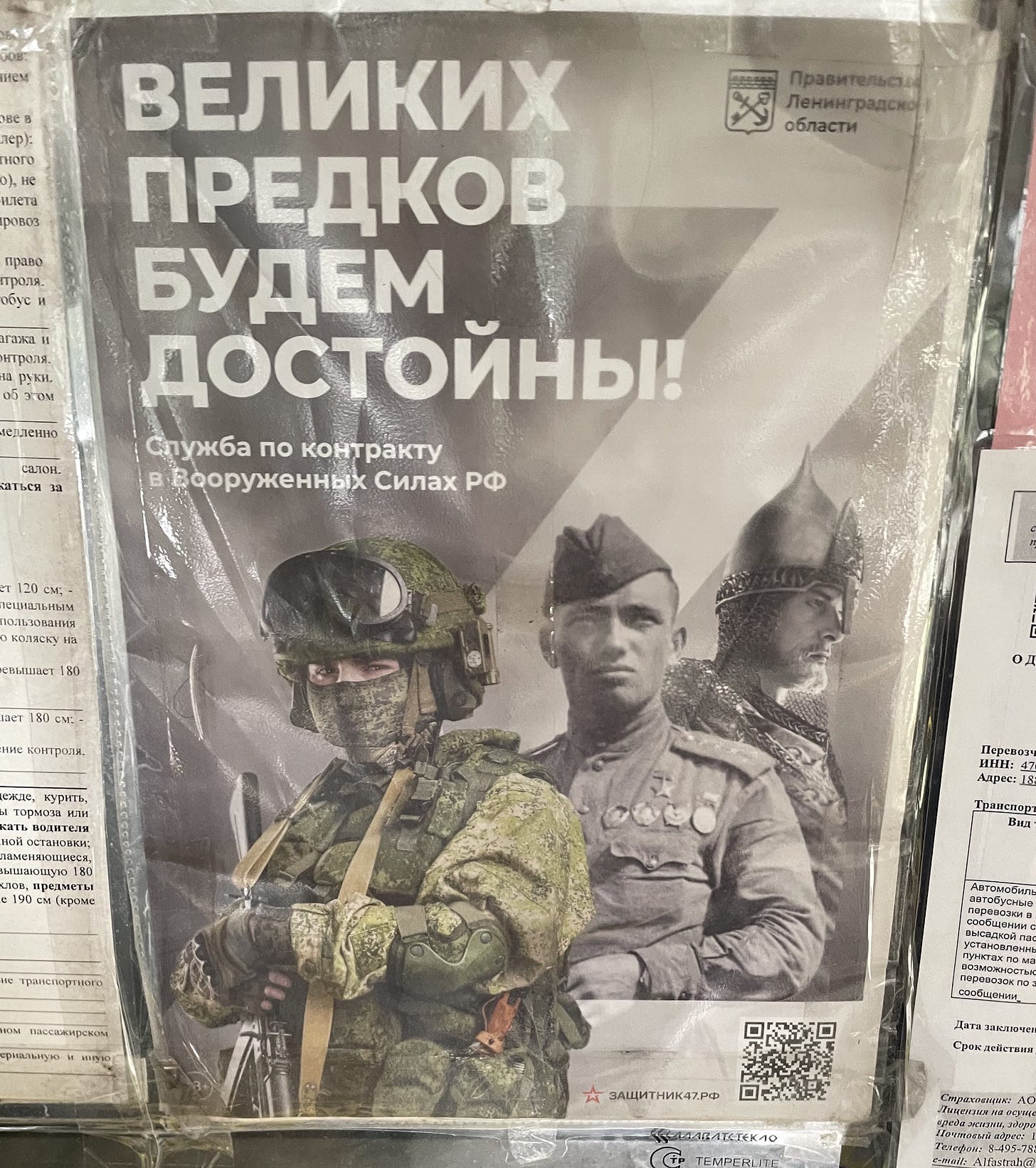

It was simultaneously everywhere and nowhere. There’d be ads in public transport encouraging enlistment (but alongside ads for all kinds of other jobs; demand for workers is high). There was a steady stream of quietly sober news reporting about the war Special Military Operation on television, which everyone seemed to mostly ignore. The city streets in Moscow and St. Petersburg were spotless, and ride-sharing taxis were easy to find via the Yandex Go app (but no more Uber, which left Russia in protest after the invasion). The police or security presence never felt very oppressive — but GPS-based location apps were at all times slightly unreliable, and sometimes stopped working entirely, because the Russian state jams GPS signals to make drone attacks harder to guide.

There was a marked lack of the usual migrant workers from Central Asia and the Caucasuses, who in past would be seen hawking goods in markets and Metro station underpasses — and a complete absence of visible homelessness or loitering. The context for this, too, was the Ukraine war: Migrants had been rounded up, coerced into “volunteering” and shipped off to the Donbas front. No doubt the homeless and other idlers were offered similar treatment.

Interestingly, it was easier to research some of this once I was back home. When I’d go on-line in Russia, media from YouTube to Twitter wouldn’t work.

Steinbeck asked, “What do they talk about in Russia?” Well, not Ukraine. At least not very much, or very openly, to me. Sometimes, to kick-start a conversation I’d volunteer my own view that Russia’s invasion, while a terrible crime, was something America would have done in Russia’s situation. My friends or acquaintances might listen with respectful skepticism, or with intense interest, but either way, few reciprocated by sharing their own cards.

One evening, I brought up the war to a friend over dinner — no one brings it up on their own — and I shared my anger about America’s role in provoking and then metastasizing this catastrophe. My friend had his own take, involving anger at Putin, concern about the vastly wealthy Russian military industrial complex driving Kremlin policy, and fear of hundreds of thousands of PTSD-scarred veterans taking huge pay cuts upon their return to Russian civilian society.

“But the war could be stopped quickly if the West stopped funding it, and stopped trying to push NATO and CIA into Ukraine,” I said.

“Maybe,” he replied with skepticism, looking down at his dinner plate, already unhappy with continuing the conversation. His wife leaned over and said quietly, “We don’t talk about the war.” She meant because it’s too emotionally upsetting, and indeed, I could see my friend was suffering. We’re all processing this in our own way, even as none of us feels any control over these events.

‘Judge How I Have Been Wronged!

Four years ago this fall, the Kremlin and the White House were gearing up to massively escalate their joint project of wrecking Ukraine. A long civil war — with one side armed by Washington and the other by Moscow — had already left13,000 Ukrainians dead. Ending the civil war had been one of the two main pledges of Ukraine’s new president, Volodymyr Zelensky (the other was to rein in organized crime in a land oft-described as “the most corrupt country in Europe”). Peace in the Donbas in those days was, according to RFE/RL, “a goal that polls have shown Ukrainians want to see accomplished more than anything.”

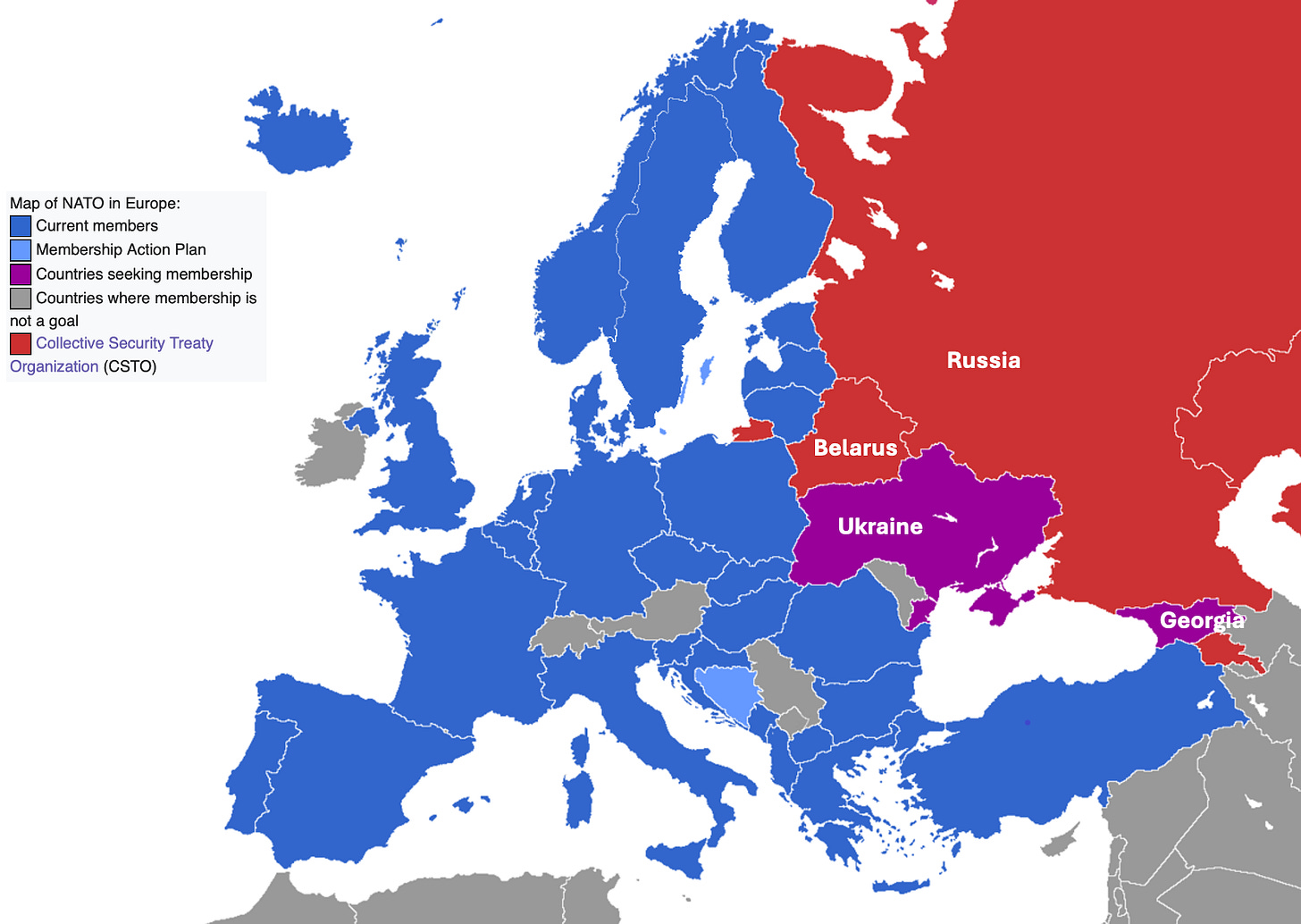

Now, instead of peace, the Kremlin was moving troops to the border and threatening a full-scale invasion — unless Washington would discuss a proposed treaty that, among other things, would freeze the eastward march of NATO and keep Ukraine militarily neutral. The White House dismissed this as “simply non-starters,” reiterated that it was not Russia’s business who NATO decided to invite in, and threatened to meet any invasion with all-out economic warfare (including an explicit threat by President Joe Biden to destroy Russia’s new natural gas pipeline to Europe).

Rimsky-Korsakoff might have summarized matters thus:

“Judge how I have been wronged!” (said the Bear to the international community).

“I had an old shoe (called Ukraine), of woven basket, torn,

for many years it lay unused.

Gray geese (from America) flew over it one day,

they took it and tore it to shreds,

then scattered the pieces in the open field.

How am I to endure this bitter wrong?

Who will comfort my brave heart?

Aren’t we going to declare a war on birds?”

Of course, that’s just some doggerel adapted from a nearly 200-year old Pushkin poem. A true-to-today fable would involve those Gray Geese moving offensive military weaponry into the open field, driving right over and crushing those old shoes, so as to better threaten Bear’s den; while Captain Wolf, Merchant Beaver, and Clerk-Treasurer Fox all slyly take their cuts of the billions of unsupervised dollars sloshing back and forth.

Russia invaded, and the West retaliated: by delivering billions of dollars of new death tech, in amounts that dwarfed that of the civil war years; and by waging the all-out economic and cultural assault we’d warned the Russians to expect.

We seized everything we could, from $300 billion of the Russian government’s foreign bank accounts to the yachts, jets and homes of individual wealthy Russians. Nor were only oligarchs targeted. Many ordinary Russians back then relied on the Western payment systems, from credit cards to cell phone-based payer apps like Google Pay and Apple Pay. They woke up one morning in 2022 and none of that worked. Suddenly, many of them could not access their money or pay their bills. All of this happened instantly, without even a pretense of legal process. (In a similar orgy of wanton, extralegal behavior, we celebrated when the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline exploded and innocently pretended not to know who was behind that.)

Side-by-side came a berserker-rage hate campaign against Russian people. Russian tennis players were banned from Wimbledon, soccer players from the World Cup, hockey players from international competition. To this day, Russian athletes are only allowed to compete in the Olympics if they renounce their home nation and agree to compete in a dreamt-up category of “Individual Neutral Athletes.” (Wimbledon also now allows Russians to compete again, provided they sign “neutrality declarations” and formally agree “not to support” Russia or Vladimir Putin.) In my home of Massachusetts, about 20 ordinary people, none of them professionals but all of them Russian (or Belarussian), were banned from the Boston Marathon that first year (and told not to expect back the $280 entrance fee), while Russian medical school graduates were told they could not study in America.

Orchestras cancelled planned performances of symphonies by Pyotr Tchaikovsky — the “1812 Overture,” about the victorious expulsion of Napoleon’s army, was particularly targeted as too celebratory. Ballet companies in New York and London struggled to defend their decision to proceed with traditional Christmas performances of Tchaikovsky’s “Nutcracker”, while the celebrity Russian conductor Valery Gergiev was fired from multiple Western orchestral positions for refusing to publicly condemn the war. (As late as this summer, a concert venue in Italy invited Gergiev to conduct a symphony but then reversed itself.) American delis renamed the Russian salad dressing used on their reubens, Russian mustard was removed from display, and restaurants in Canada and France renounced the poutine, a traditional fries-cheese-and-gravy mash-up (“poutine” is Québécois for “mess”), because it sounded too much like “Putin.” An Italian university canceled a course on the novels of Fyodor Dostoevsky (then reversed itself when critics pointed out Dostoevsky was a subversive who did time in Siberia). The International Cat Federation banned Russian cats — defined as cats owned by Russians, or bred in Russia — from competition.

It’s important to note that this unprecedented financial and cultural break with all-things Russian was occurring in the first weeks of the invasion, a time when Russia and Ukraine were both in a panic to end the crisis — had entered into intense, emergency negotiations — and had even signed provisional peace deals!

But as we were seizing bank accounts and foreign homes, and canceling tennis matches and orchestral performances and mustards and cats, and pouring in billions of dollars in death tech, we in the West also repeatedly vetoed every peace deal. That’s right: All of the long years of brutal butchery since those first few weeks were continued at American insistence.

We could have brokered a peace. Instead, our leaders told Zelensky to get back into that olive green T shirt and sell more war. Even today, as Donald Trump asks angrily why Putin won’t stop, Trump also does not offer to meet Putin’s one consistent, core demand: that we rein in NATO’s expansion.

Does this excuse the Russian government from starting a war that’s killed hundreds of thousands of young Slavic men, and displaced more than 10 million people from their homes? Of course not. But it’s valuable context, right? In the early days of the war, Russians were likely shocked at the worldwide condemnation, and alarmed at the amount of American military support Ukraine was able to field. The Russian invasion faltered, the Ukrainians pushed back valiantly, and there was talk of Ukraine turning the tables entirely — seizing Crimea, maybe even seizing neighboring parts of Russia, maybe provoking such a crisis that Putin’s rule would collapse. But predictably, when we rejected peace overtures, Russia started talking grimly about last-ditch use of small battlefield nuclear weapons. This essentially halted the Western triumphalism immediately (and Thank God for that).

In the nearly four years since, we’ve engaged in kabuki theater — buffing our yellow-and-blue lapel pins and bragging about sending 31 Abrams tanks to Ukraine, for example, in a war that has involved thousands of tanks on each side. Russia, meanwhile, has doggedly fielded hundreds of thousands of new recruits and built up its military industrial base. Its armies are larger and stronger than before the war began. By contrast, Ukraine’s youth continue to flee the country, the Ukrainian army is filled with middle-aged conscripts (the average soldier’s age is 43), and volunteers aged 60 and up are now being sought.

Russia doesn’t need our help to end the war on its own, favorable terms.

Ukraine, however, does, as President Trump this past weekend apparently again explained in another White House shouting match with Zelensky.

“If [Putin] wants it, he will destroy you,” the Financial Times quoted Trump telling Zelensky, angrily adding that he was “sick” of seeing battlefield maps of Ukraine that Zelenksy had brought, and throwing the maps aside.

“This red line [on the map], I don’t even know where this is,” Trump reportedly complained angrily to Zelensky. “I’ve never been there!”

I don’t know whether to laugh or cry. Three weeks ago, Trump was “Truth-Socialing” (I can’t bring myself to call what he does on his Twitter knockoff “Truthing”) about Ukraine having “Great Spirit”, and being poised to seize back all the territory it had lost. He’s got no idea what we’re doing there. Do any of us?

Next time, Part II: Billions of dollars for Raytheon, but a boycott for Brawny paper towels!

Honestly,fuck you Dr Matt.

My family is Russian, my wife’s Ukrainian. I am disgusted by my Russian relatives. They have a lot in common with my cousins from South Africa - deeply racist, nasty fuckers who have not a shred of empathy or compassion for any but their own, and believe they should rule over the inferiors. The last visit I made “back” to Russia was enough for me. Listening to those assholes justify Russian interference in Uraine, the theft of Crimea, the black invasion of Donbas and the corruption of Yanukovytch — all leading up to the claim that Ukrainians have been “mesmerized” by the “Jew Nazi cocaine addict” Zelenskyy. Ugh.

These revisionist histories are nauseating. NO, Matt. The US did not cause the war. And Putin was not offering peace. He was offering surrender so his invasion would be met with NO resistance. No NATO. No arms. Demilitarized and neutral. Yup. A country that could be taken in a week. THAT was his plan — are you actually that stupid or do you just pretend you greasy fuck?

I guess your in laws must be reasonably affluent - a dacha with running water and indoor plumbing.

Please spare us Part II. Apologias for genocidal mass murdering tyrants don’t interest intelligent people.,

I keep hearing how immoral Russia is over the Ukraine invasion. People have short term memories. It seems like yesterday that the US invaded Iraq.