Gain-of-Function Monetary Policy

In 2008, power over our financial markets and economy was ceded to the Federal Reserve and it's “extraordinary monetary policy.” Perhaps its time to scale it back.

As we saw during the covid pandemic, when lab-created experiments escape their confines, they can wreak havoc in the real world. Once released, they cannot easily be put back into the containment zone. The “extraordinary” monetary policy tools unleashed after the 2008 financial crisis have similarly transformed the U.S. Federal Reserve’s policy regime, with unpredictable consequences. The Fed’s new operating model is effectively a gain-of-function monetary policy experiment.

That was Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent last spring in a piece for The International Economy magazine under the headline, “The Fed’s New ‘Gain-of-Function’ Monetary Policy.”

It was timely considering the recent histrionic calls to keep the Fed “independent” over the attempted firing of Federal Reserve Board Governor Lisa Cook and President Trump’s name-calling of Fed Chairman Jerome “Too Late” Powell. Maybe it’s time to ask: should the Fed get to do whatever it wants? While it’s true that presidents appoint board members, who are then approved by the U.S. Senate, should that also mean the central bank can play God with the nation’s economy?

Bessent argues that the Fed’s policy response to both the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic amounted to “gain of function” experiments that escape the lab.

The Fed deployed a combination of sustained, near-zero short-term interest rates (Fed Funds) and a practice known as quantitative easing (QE) to “save” our economy. Unfortunately, perhaps like the Covid mRNA vaccines, the Fed had little idea what the long-term effects would be from this untested cocktail of policy medicine. Also, like the Covid vaccine, the Fed has turned its unconventional emergency response into just another tool in its kit.

The Fed’s actions had major ramifications, both positive and negative, yet they were made with relative ease. Then-Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson coordinated with the Fed in 2008, but there was no pushback or internal levers to stop their major policy decisions. Unlike the Supreme Court, where members can issue strongly-worded dissent opinions, it’s only by reading the minutes of Fed meetings that we can get a sense of what little dissent there is, as was the case in 2010, when Thomas Hoenig was the lone member to object to continuing near-zero interest rates.

The Policies: ZIRP and QE

The Fed pretty much maintained ZIRP (Zero Interest Rate Policy) until 2017 and then again from 2020 to 2022 in response to the pandemic. This punished people who put their money in savings accounts, money market accounts, and CDs — particularly retirees who need relatively risk-free interest income.

Meanwhile, it was manna from heaven for the highly leveraged players: the hedge funds, private equity funds, leveraged buy-out funds and financial institutions. Borrowed money is their oxygen. Private equity and its kissing cousin, private credit, would not be the colossuses they are today without it.

Then there’s quantitative easing. This is where the Fed boldly went in 2008 where it had never gone before. Until then, the policy was dismissed because it’s similar to a central bank printing money, which is what Germany’s Weimar Republic did, if that tells you anything.

The difference with QE is that instead of printing money, the Fed creates digital reserves to buy assets.

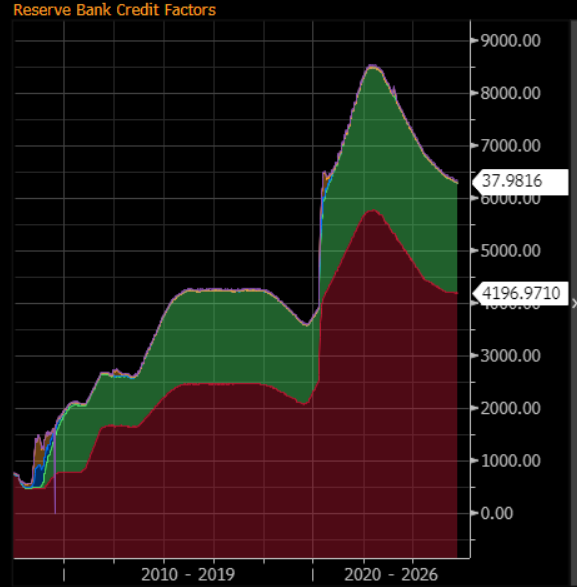

In 2008, however, after the Fed failed to recognize the subprime mortgage crisis that turned into a financial and economic catastrophe, it embarked on QE by buying trillions of dollars of U.S. Treasury notes and bonds, and Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae mortgage-backed securities (Agency MBS). The Fed did two major buying rounds of QE, first beginning in 2008 in response to the financial crisis and then again in 2020 in response to the pandemic. At its height, the Fed owned more than $8.5 trillion in Treasuries and Agency MBS — 20% of the Treasuries market and one-third of Agency MBS!

Federal Reserve Balance Sheet

Quantitative Easing Explained

Yes Virginia, the Fed created new money, and lots of it.

The way QE worked, also known in Fedspeak as POMO (Permanent Open Market Operations), was the Fed on most mornings would ask both U.S. Treasury and Agency MBS dealers (i.e., big banks) to offer them say, $3 billion of Treasuries and $2 billion of Agency MBS. By late morning, the Fed was the proud owner of another $5 billion in bonds. Wash, rinse and repeat every day. The Fed paid for these daily gargantuan purchases by electronically “printing” money and wiring it to the banks’ reserve accounts at the Fed. The Fed paid interest to the banks to encourage them not to withdraw this “new money” they were paid. It was the first time the Fed paid interest on what it calls “excess reserves.”

The Fed’s massive buying pushed up prices of these bonds. When prices go up, yields go down. The first chart below shows the immediate effect QE had on Treasury yields (represented by the 10-year Treasury yield). The second chart shows Agency MBS yields (represented by the Fannie Mae 30-year Current Coupon yield).

These important yields remained historically low until 2021. The 10-year Treasury yield averaged 2.28% (source: Bloomberg) during this period, compared to an average yield of 5.70% from 1990 to 2008

The Fannie Mae 30-year Current Coupon yield averaged 3.04% from 2008 to 2021, compared to 6.91% from 1990 to 2008.

Bringing these rates down to never-before-seen lows and keeping them there for years created both a Wall Street fantasy land and a bout of inflation in 2022 that we are still dealing with three years later.

TINA - There Is No Alternative

Treasury notes and bonds are considered “risk-free” and serve as the basis for many other financial products. When combined with ZIRP, which drove short-term yields on risk-free money market instruments to near zero, investor funds that would normally go into low–risk assets became starved for yield and were forced into riskier assets such as corporate bonds and loans, stocks, emerging markets and commodities. This phenomenon was coined as TINA, There Is No Alternative.

Long-term asset buyers like life insurance companies, pension funds and endowments, who would normally buy risk-free or near-risk-free bonds with long maturities (over 10 years) to meet their long term obligations, were pushed out of these markets. Their yields were too low. This very important investor class found yield in riskier places such as private equity funds, which in turn experienced explosive growth and minted private equity manager billionaires by the dozen.

In a perverse way, many of the Wall Street firms that caused the 2008 financial crisis, followed by the Great Recession, were first bailed out by the government and the Fed and then profited like never before from the Fed’s emergency policies that ended up being long-term. Firms made a fortune by underwriting, trading, selling, or managing stocks and risky assets.

However, for the many who didn’t have substantial assets such as stocks and bonds, recovery from the Great Recession was painfully slow and for many, non-existent.

The most popular American mortgage instrument, the 30-year fixed rate mortgage, is directly tied to the yields on Agency MBS. Therefore, when the Agency MBS yields dropped to record lows, the rates charged on mortgage loans hit record lows as well.

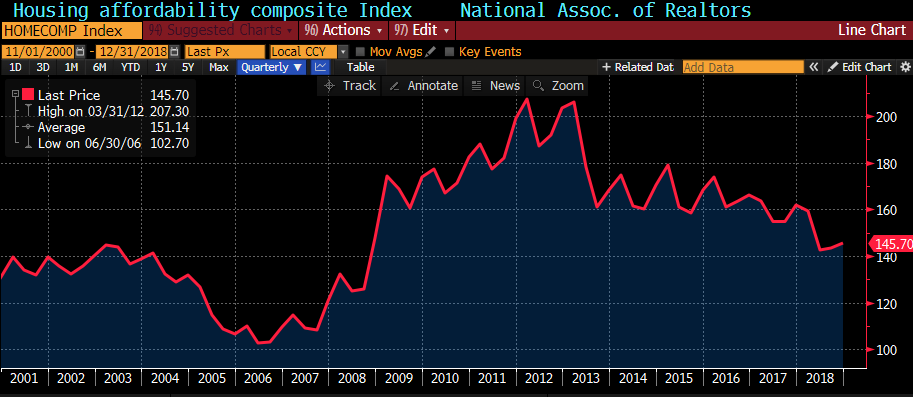

The first period of QE, 2008 to 2018 did have one positive outcome.

Thirty-year mortgage rates dropped from 6% to under 4% sparking a huge mortgage refinancing wave. If a borrower refinanced a $350,000 6% mortgage into a 4% 30-year mortgage, the net savings was about $427 a month. Additionally, lower financing costs helped increase home affordability. According to the National Association of Home Builders, construction and consumer spending on housing contribute 15%-18% to our GDP.

Unforeseen Consequences

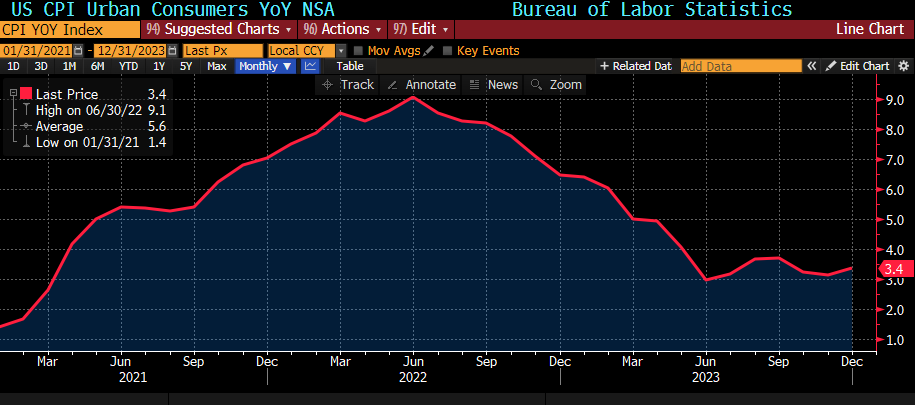

However, the second round of QE buying that began in 2020 helped stoke the painful inflationary conundrum we currently find ourselves in. The Fed’s buying drove mortgage rates to new record lows, sparking another wave of mortgage refinancing. Similar to the earlier round of QE, refinancing put additional hundreds if not thousands of dollars into millions of mortgage borrowers’ pockets every month. These savings from refinancing, combined with government Covid stimulus and supply chain disruptions, created our most serious inflation bout since the 1970s.

Inflation in the U.S. began rising in the spring of 2021 at an alarming rate. The Fed at first believed the inflation spike was “transitory,” kept up its pace of QE buying until late 2021, and didn’t stop new purchases until March 2022. Raging inflation forced the Fed to raise the Fed Funds rate at a rapid pace, and in response to both the Fed slowing QE purchases and surging inflation, 30-year mortgage rates went from 3% to 7% in the course of a few months.

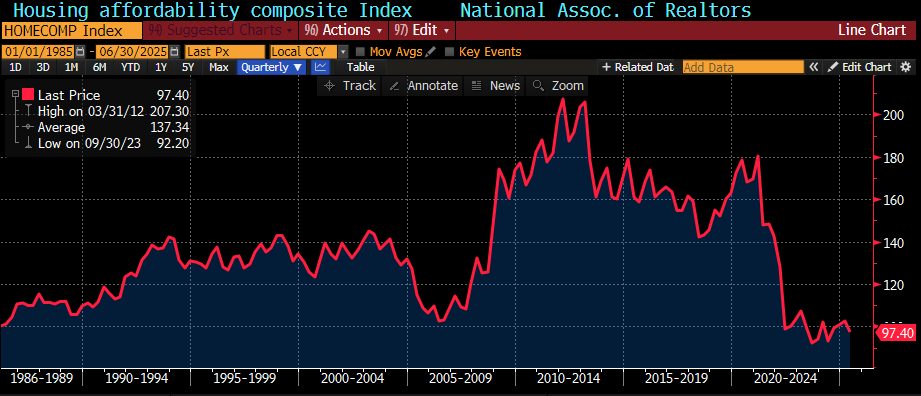

This huge increase in mortgage rates created a huge, unforeseen problem. The refinancing wave QE put millions of homeowners in historically low-rate mortgages, of 2.5% to 3.5%, creating a lock-in effect. Homeowners who would like to move often don’t because they cannot afford to go from a 3% mortgage to a 6% mortgage. The lock-in effect has disrupted the natural supply flow of the housing market as existing homeowners keep their houses off the market. The combination of higher mortgage rates and lack of existing homes for sale has driven housing affordability to record lows. As housing is vital to our economy as well as personal wealth building, this unforeseen development is having major consequences.

Before 2008, the Fed had a tremendous amount of power and influence over the lives of every American. After 2008 their use of ZIRP and QE allowed them to play God with all our lives, unchecked. The independence of the Fed isn’t all or nothing. While I don’t think the President should be able to force the Fed into raising or lowering interest rates, there needs to be some sort of circuit breaker that requires a sign-off from constitutionally elected government officials before using extraordinary policy measures like ZIRP and QE.

Last year, Stephen Miran and Dan Katz of the Manhattan Institute published a paper, “Reform the Federal Reserve’s Governance to Deliver Better Monetary Outcomes.” Interestingly, Trump appointed Miran last month to the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors.

Miran and Katz proposed shortening the terms of Fed governors, currently 14 years, and increasing the influence of the 12 Federal Reserve banks by allowing their presidents to vote at each Federal Open Market Committee meeting. Currently, only five can vote on a rotating basis. The proposal also calls for state governors in each bank’s district to appoint their boards of directors. The thinking is these changes would make the Fed more democratic and provide more accountability.

Perfect? Maybe not, but we definitely need more thoughtful conversation and action on the subject. The status quo isn’t working.

When the money is fake, the rest of the economy is doomed to follow.

The problem is that they CAN'T just shut off the money faucet because now the "economy" relies on it. And as any fan of history knows, when the fake economy of getting rich by being close to the literal money-making machine overtakes the real economy of mutually exchanging goods and services, the wheels come off the bus.

Audit the Fed/END THE FED. This has been a 100 year failed experiment.