NOTE: This is material from “The Writing Life.” If you do not want to receive these articles you can click on this page, https://www.racket.news/account, to opt out of receiving future email notices.

I’m old enough now to worry about leaving things for my sons to read when I’m gone. Eventually I’ll have to explain how I went from being a depressed teenager who hated authority figures and was addicted to life-imperiling activities (and drugs, eventually), to being the near-functional adult they know, whose authority problem is whittled to manageable levels.

In my mind’s eye I imagine sitting them on a knee and saying, “Boys, finding a way to monetize your severest personality disorders is the promise of the American dream.” But, the image doesn’t work. For one thing, by the time they’re old enough to understand, they’ll be too huge to sit like that. Also, it’s the wrong message.

I went from unwell to happy by reading, but it took thirty years. The process could have been shortened if someone had picked the right books for me at the start. Hence the idea of putting together an anthology. If any of my children have the misfortune to turn out like me, this letter from the past may help provide a map to an approximation of sanity.

The first book that turned out to matter in my adult life featured a short story called How a Muzhik Fed Two Officials.

I was fourteen and disinclined to anything taught in school. I still suspect many curricula are designed to turn kids off to reading. Some teachers view reading as an exercise in torturing a book until it screams and confesses its “message.” I recall being assigned, too early, texts by the likes of Chaucer or William Faulkner, whose pages seemed indecipherable even to the adults “teaching” them. In class, we’d be asked: “What is the author trying to say?”

If you have to ask what an author is trying to say, it seems clear he or she is not saying it well. But instructors insisted a good book was something not immediately enjoyable to read, containing an Important Message written in oblique language so its meaning could be divined via an ennobling ritual of painstaking research and group analysis. This seemed the same thing as Catholic church, another operation I was souring on.

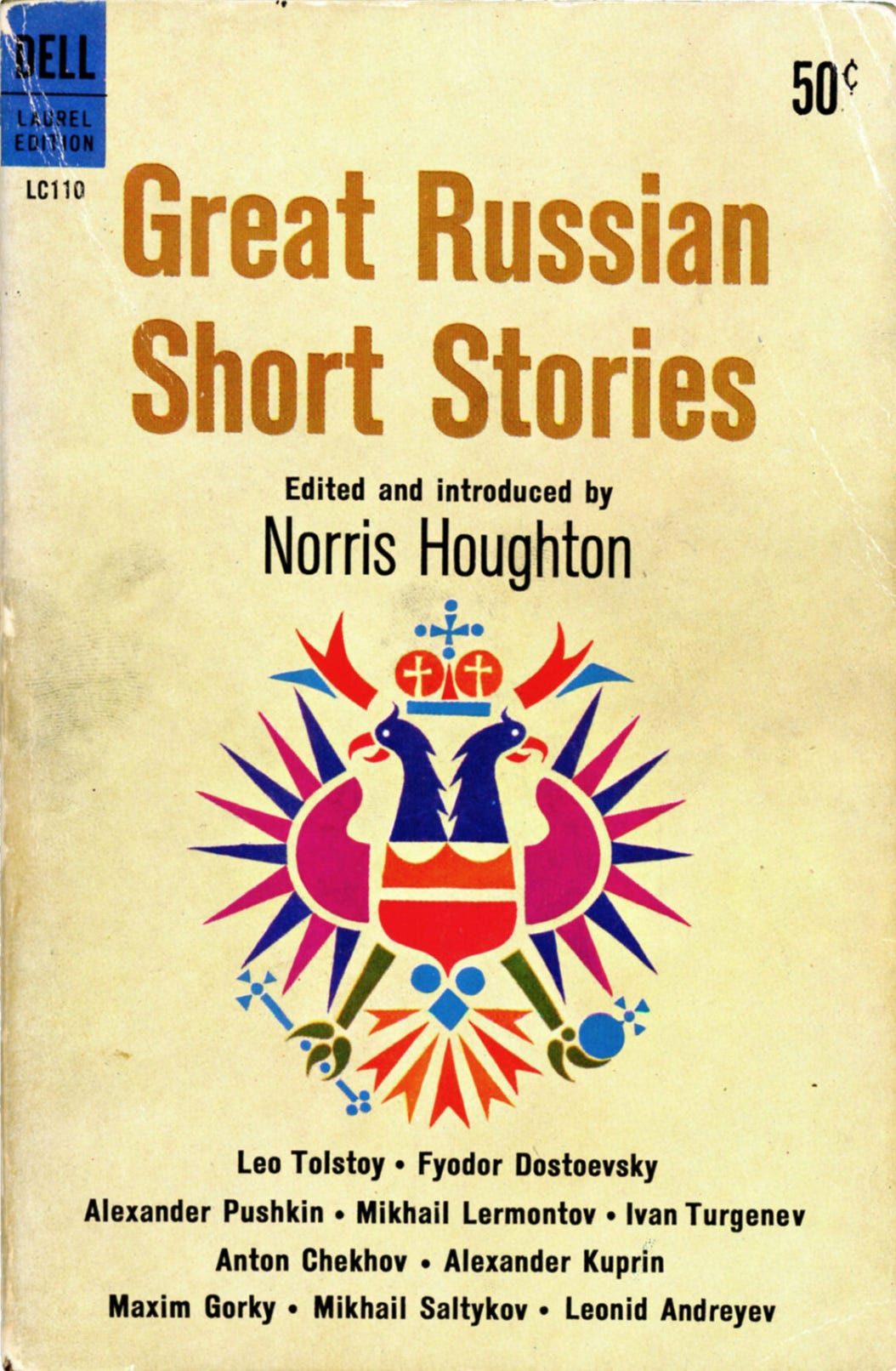

One of the few teachers I liked gave me an old copy of Great Russian Short Stories, edited by Norris Houghton. This teacher was a funny person who would often interrupt class to ask if he had something on his nose (he didn’t), and it was rumored that he had a dentist’s chair in his basement, for no reason. The rumor turned out to be true, as we learned on a class visit to his home. Whatever this teacher was about, I was drawn to it, so I made an effort with the book.

I liked the Houghton paperback. Its page-edges were stained a silly turtle-green. (These things matter.) The cover illustration featured a cartoon Tsarist double-eagle, like a Joe Camel logo for “Russian literature.” The book was also beaten from use, to the point of being soft as a baby’s blanket to the touch. Like the Velveteen Rabbit, who became Real as its boy-owner played with and adored it, when a book is worn it usually means it was loved by someone, and is therefore often pleasurable to the touch. To this day I distrust old books that feel new, a la the “Great Literature” sets some people buy to fill shelves, with pages freshly cut or even stuck together from unuse ten years later .

Speed-flipping though the anthology, I stopped on How a Muzhik Fed Two Officials, by someone named Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin. It was a few pages long, appeared to be nearly all dialogue, and low on long words. It began in spoof fable language:

Once upon a time there were two Officials. They were both empty-headed, and so they found themselves one day suddenly transported to an uninhabited isle, as if on a magic carpet.

They had passed their whole life in a Government Department, where records were kept; had been born there, bred there, grown old there, and consequently hadn’t the least understanding for anything outside of the Department; and the only words they knew were: “With assurances of the highest esteem, I am your humble servant.”

Having introduced his fairy tale heroes, Saltykov-Shchedrin described their surprise dilemma:

Waking up on the uninhabited isle, they found themselves lying under the same cover. At first, of course, they couldn’t understand what had happened to them, and they spoke as if nothing extraordinary had taken place.

“What a peculiar dream I had last night, your Excellency,” said the one Official. “It seemed to me as if I were on an uninhabited isle.”

Scarcely had he uttered the words, when he jumped to his feet. The other Official also jumped up.

“Good Lord, what does this mean! Where are we?” they cried out in astonishment.

A teenage boy who can’t connect with a story whose premise is Morons Awake on Desert Isle is probably not going to read at all. I had total buy-in by the first few paragraphs.

Saltykov-Shchedrin’s Tsarist functionaries — Russian is an onomatopoeic language and the word for such bureaucrats, chinovniki, sounds like what they are, “pea-brained pseudo-people” — spent their whole lives in copying offices and couldn’t begin to figure out how to take care of themselves. Where does food come from? How does wheat that grows out of the ground become a hot roll? Why does the sun rise in the East and set in the West, instead of the other way around? (That’s easy, one of the gentlemen decides. Because we always go to our offices when the sun rises, and go home when it sets, and we couldn’t do it the other way around).

They search the island for food, and though they find brooks overflowing with fish, and woods thick with partridges, they don’t know how to catch any of these things. The only thing they can get hands on is an old copy of the Moscow Gazette, and who can eat that? They start weighing the percentage in eating boots or gloves. Next, madness of the type that really does occur in people dying of hunger hits these fellows, only it sets in not after a week of wandering a desert or floating at sea, but a few fleeting minutes of discomfort:

The two Officials stared at each other fixedly. In their glances gleamed an evil-boding fire, their teeth chattered and a dull groaning issued from their breasts. Slowly they crept upon each other and suddenly they burst into a fearful frenzy. There was a yelling and groaning, the rags flew about, and the Official who had been teacher of handwriting bit off his colleague’s order and swallowed it. However, the sight of blood brought them both back to their senses.

The brush with cannibalism chastens the friends for a moment. They try to talk through their dilemma, but no matter what they discuss, conversation turns to food. Making what seems like the first good decision of the story, they elect to stop talking altogether, which grants them just enough self-possession to read that Moscow Gazette Saltykov-Shchedrin skillfully introduced a few paragraphs before.

A sign you’re dealing with a master is when you see the joke coming from miles off and it’s still funny when it hits. Once the Officials “began to read eagerly,” you knew in your gut what they’d find on the page:

BANQUET GIVEN BY THE MAYOR

The table was set for one hundred persons. The magnificence of it exceeded all expectations… The golden sturgeon from Sheksna and the silver pheasant from the Caucasian woods held a rendezvous with strawberries so seldom to be had in our latitude in winter…

The two are on the verge of total despair when one of the gentlemen comes up with a solution: find a muzhik, i.e. a manservant. That’s what they’d do at home, after all.

The difference between a good and a bad writer is that instead of tracking with logic, the good writer’s inventions track with the unpredictable arc of the universe. It makes sense that clerks marooned on an island would pine for domestic service, but it takes genius to see a servant would in fact be there. Throughout history, outnumbered nitwits have been surrounded by a limitless supply of supplicating skilled helpers, and the reason for this is… Well, as Russians would say, Bog znayet shto, i.e. God knows why. Saltykov-Shchedrin captures how his idiots save the day by remembering this eternal truth just in the nick of time, at which point help for the marooned pair magically appears.

“Hm, a muzhik,” says one. “But where are we to fetch one from, if there is no muzhik here?”

The other replies with flawless aristocratic reasoning:

“Why shouldn’t there be a muzhik here...? There certainly must be a muzhik hiding here somewhere, so as to get out of working…”

They wandered about on the island… until finally a concentrated smell of black bread and old sheep skin assailed their nostrils... Under a tree was a colossal muzhik lying fast asleep with hands under his head. It was clear that to escape his duty to work he had impudently withdrawn to this island. The indignation of the Officials knew no bounds.

They officials wake the muzhik up, chastise him for laziness, and start ordering him around. Caught out, the servant resigns himself to his fate: “He had to work.” Next thing, the officials are eating huge meals and warming by a fire. The muzhik asks if he can rest. Officials generously grant permission, as soon as their savior makes a “good strong cord.” Saltykov squeezes in a last bit of mischief describing how expertly the muzhik lays “wild hemp stalks” in water and beats them, fashioning from nature’s raw materials the rope his new masters will use to tie him to a tree.

This is where the schoolteacher interjects in triumph: “See! The story has a message after all! Saltykov-Shchedrin is making an important point about class exploitation! He depicts the working class forging the very chains the bourgeoisie uses to wrap it in submission!” And so on.

I’m not sure. As I hear that imaginary teacher’s voice, I imagine him stopping mid-scold to slurp a sip of the fragrant hot soup that, by the end, the industrious muzhik has learned to cook “with his bare hands.” The story is too real to be preachy. To me this is mostly just a hilarious tale about how the world tends to bend toward jackasses, who seem always to end up in charge even if they can’t find their backsides with a map.

The story ends when the men order the muzhik to construct them a ship that takes them back to their home in St. Petersburg. Problem solved!

Saltykov-Shchedrin is brutal to his clerks, but makes them out to be as much victims as monsters. Like perma-scrolling New Yorkers who walk up and down 6th Avenue so engrossed in Current Thing controversies that they’ll walk groin-first into parking meters or traffic even, the ink-stained clerks of the Tsarist era had heads so pumped full of propaganda that there was scarcely room in there for anything but directions to the office.

Today’s netizens are the same. They can conjure six different Amish porn sites in a snap, but would die of exposure if left outside without phones for a night, even surrounded by flint and firewood.

Saltykov-Shchedrin had the misfortune to live and work in an era that produced some of the greatest prose artists of the modern age, from Tolstoy to Gogol to Dostoyevsky and Turgenev. He was also cursed to live in an era of Russian history overpopulated with some of the most pretentious literary critics ever, many of whom lauded the “literature of social intent” and became intellectual forefathers of one of the unfunniest ideas ever, Bolshevism.

In the assessment of such critics Saltykov-Shchedrin was often demerited for “laughing for laughter’s sake.” It’s one of a writer’s greatest compliments.

As a young person all I knew was that his story took a few minutes to read and made me laugh out loud a half-dozen times. It didn’t make me hate people, but did suggest taking them less seriously. If you’re beginning a reading life, this small, perfect, hilarious fable a good place to start.

I've also concluded that the purpose of schooling is to make people never willingly pick up a book again. You captured the painful analysis of 'literature' well. It got me to re-up my subscription.

"If you have to ask what an author is trying to say, it seems clear he or she is not saying it well."

Bingo. When it's not just incompetence complexity is often camouflage for a bamboozle.

Such a joy reading your writing!