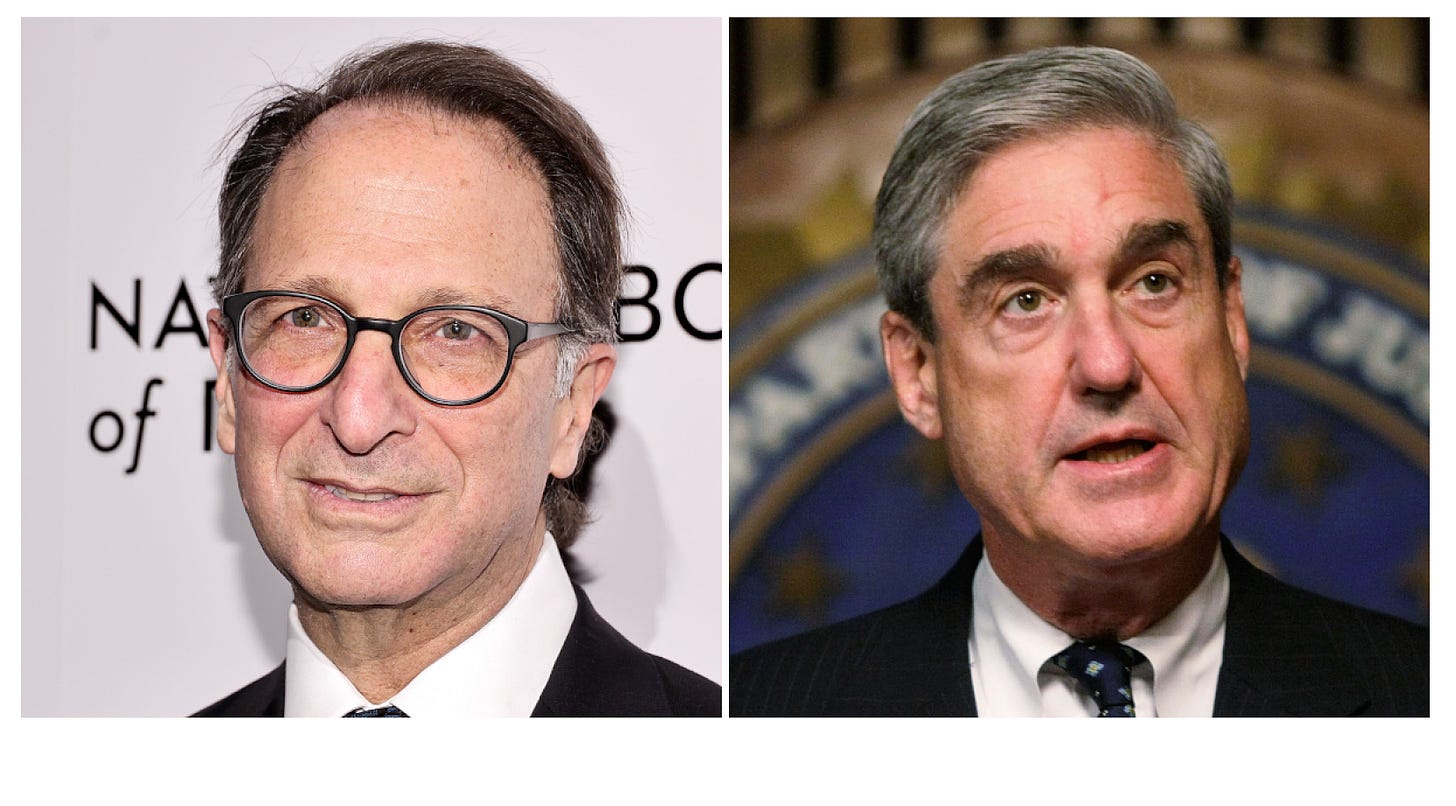

Exclusive: Andrew Weissmann in Crosshairs as War on Big Law Continues

Longtime deputy to Robert Mueller and key Trump-Russia investigator Andrew Weissmann is in the crosshairs of federal prosecutors

For years, Andrew Weissmann was one of the most visible and vociferous critics of Donald Trump, as a former deputy to Special Prosecutor Robert Mueller and MSNBC legal analyst who wrote a book wondering if the president “paid bribes to foreign officials,” or had “Russian business deals in the works” when he ran for president.

Now Weissmann is facing hard questions of his own, about eerily similar themes.

In a pair of letters obtained by Racket, District of Columbia U.S. Attorney Ed Martin demanded to know why Weissmann ignored an alleged “conflict of interest” in signing off on a $4.5 billion settlement involving the Brazilian construction conglomerate Odebrecht in 2016, the largest such case in history. Weissmann had been (and is now) a partner at Jenner & Block, which represented a reputed key player in the story, a Canadian private equity firm called Brookfield Asset Management that until January was chaired by that country’s new Prime Minister, Mark Carney.

From Martin’s letter to Weissmann:

Under your leadership, the Fraud Section participated in investigations concerning Brookfield — your office called one case, the federal investigation of the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht, “the largest bribery case in history.” Somehow, Brookfield and its proven corrupt subsidiary, Rutas de Lima, were excluded from sanctions. After you ordered investigations into Brookfield closed, you then returned to Jenner & Block in 2020 as co-chairman of its investigations, compliance, and defense practice.

The letters sent Tuesday, March 11th to Weissmann and Jenner & Block co-managing partner Ishan Bhabha (PDFs at bottom of page):

Neither Weissmann nor Bhabha has responded to a request for comment. A spokesperson for Brookfield said the firm hadn’t heard of the letter, and asked for more information. We’ll update when any of these parties comment. Weissmann, it should be noted, over the years frequently implied Trump was a coward for failing to sit for interviews under oath or “even for an interview.”

The country’s biggest law firms, the politically active and highly compensated defenders of banks and takeover artists and weapons makers, look like the Trump administration’s next PR meal. Last Friday, Trump gave a speech at the Justice Department before Attorney General Pam Bondi and FBI head Kash Patel announcing a sweeping campaign against various “wrongs and abuses.” When he brought up lawyers and law firms, Weissmann’s was the first name he mentioned.

“The same scum you have been dealing with for years. Guys like Andrew Weissmann,” he said. “Deranged Jack Smith. There’s a guy named Norm Eisen, I don’t even know what he looks like. His name is Norm Eisen of CREW; he’s been after me for nine years… These are bad people.”

Trump’s personal feelings toward the lawyers who gamed the Steele letter or tried to jail him on various theories notwithstanding, the new letters should be understood as part of a broader Trump campaign to investigate the legal sector, which is suddenly under heavy fire. A March 6th Executive Order targeting the Clinton-aligned firm Perkins Coie for its role in promulgating the Steele Dossier raised eyebrows, and was criticized by the National Review for moving too far in the direction of mere “payback.”

Still, despite Weissmann’s status as a ferocious Trump critic and symbol of Russiagate, the Jenner & Block letters hint at wider institutional issues. “The problem is, all of Washington does this,” says an administration spokesperson. “The revolving door has turned into something completely corrupt, and that the weaponization of government is often coordinated from K Street. The administration wants it stopped.”

Odebrecht is a giant construction conglomerate, a Brazilian analog to the Dick Cheney-connected KBR/Halliburton, ironically also implicated in a global bribery scheme. The Odeberecht case was exponentially bigger, involving at least $788 million in illegal payments to officials all over the world, as a means of rigging bids and securing contracts.

Weissmann’s firm Jenner & Block has long represented Brookfield, which jumped into a Peru deal at an odd time. Odebrecht CEO Marcelo Odebrecht was arrested in 2015, sentenced in March, 2016 in Brazil on bribery, money laundering, and organized crime charges, and rolled up in history’s biggest-ever bribery settlement in December, 2016, in a deal signed by Weissmann. In between, Brookfield in June 2016 bought from Odebrecht a 57% stake in Rutas de Lima, a Peruvian toll road authority. The settlement bearing Weissmann’s name did not mention Brookfield or Rutas de Lima.

With Odebrecht’s legal troubles it was able to buy a controlling stake in Rutas de Lima for an advantageous price of $430 million, a seemingly risky gamble given that the U.S. could have named Odebrecht’s Lima project in its settlement. Instead the settlement offered little detail about the specific contracts at issue, which one lawyer connected to the case believes offered “unusual” protection to Brookfield’s investment.

“When a plea agreement fails to specify which projects were tainted by bribes, it creates massive obstacles for victims like the City of Lima,” says Martin De Luca, a former federal prosecutor in the Southern District of New York who now represents the City of Lima in its dispute with Brookfield. “The vague and incomplete terms of the Odebrecht plea deal have not only hindered Lima’s ability to seek restitution but have also allowed Brookfield to exploit the ambiguity—profiting from a toxic asset acquired for pennies on the dollar.”

It’s important to note that the U.S. District Court in DC just last year denied an application by the municipality of Lima to void the Rutas deal on corruption grounds, given that it would be “difficult… putting it mildly” to prove misconduct given the failure of prior inquiries like the American investigation to point a finger at the group.

However, public records inside and outside the U.S. are full of allegations tying Rutas or Brookfield to Odebrech’s practices, making it difficult for any lawyer to claim there could be no perception of a conflict. Odebrecht won the Lima toll road contract in 2012 in a process that supposedly included “steps to attract bidders,” but was awarded without competition. The deal was one of many elements that spurred a recall vote against Villarán in 2013, which she survived. She would later be indicted for allegedly taking money from Odebrecht to help her win that recall vote.

In 2017, shortly after the American Justice Department finished its Odebrecht settlement, Rutas/Brookfield announced a rate hike for the privatized road, moving the price to 10 soles, about $3 a day roundtrip, or about two and a half times the hourly minimum wage at the time. The deal, in which private equity conquistadors pull two-and-twenty fees from investors chasing Peruvian workers for overpriced tolls, appears a textbook case of privatized exploitation from afar. It’s a strange endeavor for ostensible progressives like Carney or Weissmann to be involved with, and exactly the sort of thing American progressives howled about when the Abu Dhabi investment authority bought 75 years of Chicago parking meter revenue and not only raised prices, but canceled free parking on Lincoln’s birthday.

The price hikes, in addition to alleged efforts to block alternative methods of entry to the city, spurred violent street protests:

“This case underscores how opaque plea agreements can shield financial beneficiaries of corruption while leaving actual victims to fend for themselves,” says De Luca.

The broader issue has to do with the enormous volume of settlements and cases that run through the American justice system, often managed by titantic defense firms that almost by design have deep ties to the world’s largest corporate clients. The revolving door phenomenon, in which lawyers from hotshot defense firms take brief sojourns in the public sector before returning to their same spots as corporate defenders — think Eric Holder, whose firm Covington & Burling literally kept his office for him while he served as Obama’s Attorney General. Covington, along with the fellow white shoe big-timers at Paul, Weiss, are now facing scrutiny because of Covington vet Jack Smith’s prosecutions and a J6 case, respectively.

The Trump administration’s moves against Covington & Burling, Paul Weiss, Perkins Coie, and now Jenner & Block will all likely be criticized as overreaches that threaten “the ability of private citizens to obtain lawyers,” as the New York Times put it. “Trump’s retribution is that he won the presidency,” added the National Review. “It is not turning the presidency into lawfare on steroids.” Whatever one thinks of these criticisms, most of them leave out the context that broad-scale attacks on law firms and lawyers who represented Trump began under the previous administration, notably through efforts like the 65 Project, which sought to punish lawyers and firms who represented Trump. It may be extreme to indict a whole firm based on the behavior of a few lawyers, but Sixth Amendment disrespect cuts both ways.

Still, what if the accusations are right? What if financial conflicts are built into every level of the system, in the same way abuses appear to have been built into federal contracting? Either way, the era of self-congratulatory cultural portraits for big law along the lines of The Good Wife or The Good Fight appears over, as the trend of previously unimaginable glimpses into the underbelly of institutional America continues. Is it ugly, personal, and maybe also true?

A March 6th Executive Order targeting the Clinton-aligned firm Perkins Coie for its role in promulgating the Steele Dossier raised eyebrows, and was criticized by the National Review for moving too far in the direction of mere “payback.”

Fine, call it payback. But what we need is some basic legal accountability for this pile of malice we had to deal with for the last eight years.

Andrew Weissmann was involved in the Mueller coup against the democratically elected president Donald Trump. He's also been directly involved in at least half a dozen men going to prison that he knew were innocent just to make himself look good and better his career.

Here’s to the DOJ locking Weissmann's sorry ass up for the rest of his life.