Do Your Own Research: How to File Your Own Freedom of Information Requests

Interview with Allan Blutstein, who helps run a site that explains the ins and outs of filing FOIA requests

Public records are a key part of Racket’s library project—not just for the stories we cover, but as a resource to help you access the records that matter to you. I figured talking to a guy with “FOIA” as his vanity license plate would be a good place to start.

Allan Blutstein helps run a site called FOIA Advisor. It’s a labor of love among Blutstein and two others that he jokes is funded by his credit card. All three are involved in conservative politics for their day jobs, but FOIA Advisor is for anyone. It has a roundup of FOIA news, FOIA-related court cases, links to searchable FOIA regulations for federal agencies, samples of FOIA appeal letters by conservative and liberal groups, FOIA letter-generator sites, and electronic reading rooms where you can access records and see what other people are requesting.

The reading rooms are helpful. For one, their FOIA logs remove the need to FOIA all FOIA requests as I did back in the day. Blutstein also says they can be tremendously helpful in crafting your own request. Blutstein should know. He worked at the Justice Department responding to FOIA requests. He was also principal legal counsel for FOIA staff at the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Financial Stability. Now, he’s director of FOIA operations for the America Rising Corporation. Our conversation with him, edited for clarity and brevity:

Racket (Greg Collard): Which features of FOIA Advisor are most popular?

Allan Blutstein: Our summaries and postings of court opinions. There are hundreds of federal court FOIA cases issued every year and we try to keep on top of that. My former office of the Justice Department also summarizes cases, but they’re usually a month or two behind and they don’t post the actual decision. They will give long summaries. I’m not sure if that’s for trademark intellectual property purposes or why they won’t post the actual decision. So I think that’s our most popular feature. And also just daily news, what’s happening in the government and the world. And some educational resources that we have.

GC: What are the types of things that people are most interested in getting information about?

Allan Blutstein: All sorts. We’re mostly geared toward the federal Freedom of Information Act. While we don’t track state court decisions — we simply can’t keep up — if anyone asks us a question about a state law, we’ll do our best to steer them in the right direction. The other day, a rather significant decision was issued about whether [DOGE] records are subject to Freedom of Information Act requests. We’ll see how that one plays out. I imagine the administration might fight the district court on that, but the department that gets the most requests every year is DHS. Far and away they get more than half of all federal FOIA requests. Immigration records are particularly popular. The Department of Justice and the Department of Defense are also quite popular with FOIA requesters. At DOJ, the FBI and all the law enforcement agencies get lots of requests, including from prisoners who want to re-litigate their criminal cases.

GC: They have a lot of time to file.

Allan Blutstein: They have a lot of time and some of them are quite good. I was impressed when I was at the Department of Justice. Some became jailhouse lawyers. They were quite good.

GC: Say someone wants to get information on how federal Title I funds are spent on certain schools… What’s your advice on how someone should start? Should they file a FOIA request immediately?

Allan Blutstein: That’s a good example. I would say go on the Department of Education’s website. Financial information is not typically controversial and a lot of it will be posted online. So I would start there. Really for almost any type of request, I might first go to an agency’s electronic reading room to see what they’ve posted. If nothing’s there on the website, I might look at their FOIA logs if they’re published. This is a list of requests that other individuals have filed. They’re often posted online. If you are interested in something, it’s likely that someone else also has an interest and they may have already requested records. That’s helpful just to get an idea of what an agency has and what other people have asked for. And also to help you craft a request. You can just copy what someone else has done or just ask for a file that’s already been processed. Just ask, “I’d like request number 255 that you received two months ago.” And you can just feed them the information, which makes it very easy. You’ll get much quicker turnaround times if you just piggyback off someone else’s request than inventing your own.

Now, there are some strategies. You’ll get better as a requester as you do more. You’ll learn what a burdensome request is that might make agencies push back. Your requests don’t need to include a lot of legalese. You don’t need a lot of definitions. They don’t have to be five pages. You don’t need long introductions. You don’t have to explain why you want the records. Agency personnel generally don’t ask. There are very few circumstances in which they need to know legally. So, a lot of background isn’t necessary. You want the person on the other side to understand what you’re asking for. Sometimes some context helps. FOIA personnel don’t know everything that’s happening in their own agency. The Pentagon is a big place. They may not know about the document that you’re interested in. So providing some background to facilitate the search is a good idea. But your request should be reasonably specific.

Some requesters in the business are looking for publicity. So they will include a long explanation at the front because they want reporters to pick it up, but that’s not for the average person. They’ll ask the agency to expedite their requests and argue why they’re entitled. They’ll argue why they’re entitled to be considered reporters, and they’ll argue for a fee waiver all upfront. They’ll include long definitions. They’ll remind the agency of what the response time is, and they’ll remind the agency that if they make redactions, if they withhold information, to explain why.

I tend not to include all these reminders, having been on that side. The agency knows the law. Law firms or lawyers who might be getting paid to make the request tend to include what I call “fillers.” It’s just perhaps to impress the client, but it’s really irrelevant. I would say skip it.

GC: Can you explain electronic reading rooms for people who may not be familiar with what they are?

Allan Blutstein: Before the electronic age — the old days, in the 70s and 80s — federal agencies had actual libraries where the public could visit. Now, federal agencies have on their websites FOIA pages. FOIA Advisor has a list of all the reading rooms. You can just click the links where agencies are required to post certain information as well as frequently requested information. And so that could save you quite a bit of time. I would say don’t hesitate to send a request. The government is not tracking you. They will not retaliate. This is a legal right that citizens and non-citizens have to ask for records.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that you will obtain all the records that you asked for, but there’s no harm in requesting. You might have to wait a while. And that’s another key piece of advice: be patient. Although there are legal deadlines, those are more often not met. Those who have not made requests before might have trepidation about whether their requests are public. Will their names be publicized? Will I upset a government official? And the answer to that last one is no, at least at the federal level, FOIA requests are employing 6,000 people, so keep them coming.

GC: There are 6,000 people that deal only with FOIA requests?

Allan Blutstein: Yeah. The data just released for fiscal year 2024 shows that full-time FOIA staff increased from about 5,000 the previous year to a little over 6,000. Now that’s changing rapidly [because of government cutbacks].

GC: So does that worry you for fulfilling public records requests? Is it going to be a challenge to get public information?

Allan Blutstein: It will be at some agencies that are not exempt from both the federal hiring freeze and from recent layoffs. So I think DHS should be OK, and DOJ. But you mentioned the Department of Education. It looks like they’re trying to reduce their workforce by 50% and they may try to shutter it all together. So I think response times to requests this year will increase at many agencies. In fact, there was a news story where someone made a request to OPM and an employee quipped, “Good luck with that. They just fired the privacy staff,” or something along those lines. So wait times are likely to increase at the federal level.

GC: When you’re filing local requests, say with your local school board or town hall, what should that approach be? Should you file FOIAs immediately or talk to staff first? At least in my experience, sometimes it’s a different process to get what you want.

Allan Blutstein: Generally the FOIA process is an arm’s length transaction, and so personalities don’t have a lot to do with it. That might be different with local officials. If an office is particularly small, maybe you can get on the phone first and just ask, “Hey, can you help me out?” Or, “What’s the best way to get this type of information?”

I tend not to do that, but I think reporters do. They’re just more comfortable dealing with people like that. It’s sort of a double-edged sword. With local agencies, they may get fewer requests, so you’re not waiting as long, but they have collateral duties, so they’re not dedicated. They’re not sitting at their desk processing requests all day. It certainly helps to be friendly. I try to do that. They are human beings on the other side, and I was there. Saying please, the thank you’s — don’t harass them every week asking for an update. There’s something to be said for that. Being professional and courteous is good advice.

GC: Fees are sometimes a big issue (and were, especially before electronic records). Do you get a lot of questions about having to pay fees?

Allan Blutstein: The government in recent years collected about $2 million in fees, but that’s a fraction of 1% of what it costs to process and run the FOIA system, which is over $600 million. So they’re not collecting that much. The ordinary requester, Joe Requester, who’s just curious about getting some records, they are charged only after two hours of search time. So if the records can be retrieved in less than two hours, they’ll get that information for free. Duplication costs only apply if you’re getting hard copies. You’ll pay 10 or 15 cents a page, but you’ll get the first 100 pages for free. I would say duplication fees, in this day and age, are usually nothing. If you’re a commercial requester intending to use the records for profitable purposes, they will get charged for review time. Also, if an attorney or anyone needs to review the records to redact them, they’ll get charged as well.

You can apply for a waiver of fees under certain circumstances. There’s no waiver on the federal level for indigency. That might be a reason for a waiver at the local level. I hear more complaints on the local level about fees, especially here in Virginia. It really varies by state. If you’re asking for years worth of emails, voluminous records, you are more likely to incur a fee. So at the federal level, if an agency misses their response deadline, they forfeit the right to collect certain fees. Reporters, members of the media, are a favored fee category. They will not be charged for search time so reporters are essentially getting records for nothing. And there are a few other preferred fee categories. If you’re making a request for an educational institution, for instance, a university professor doing research or a non-commercial scientific institution.

GC: What’s your advice for people on the local level who are asked to pay, say, 25 cents a page?

Allan Blutstein: Well, oftentimes if you want to inspect the records as opposed to getting copies, that might be an option. So you can for no charge, look at the records first and then determine what you’re willing to pay for. Because often their requests might be broad. You’re asking for records about a subject matter that may be emails that contain certain search terms and what you get back might be more than you expected. You may be getting back responsive but irrelevant records that you’re not interested in. So before paying them, perhaps you can inspect them.

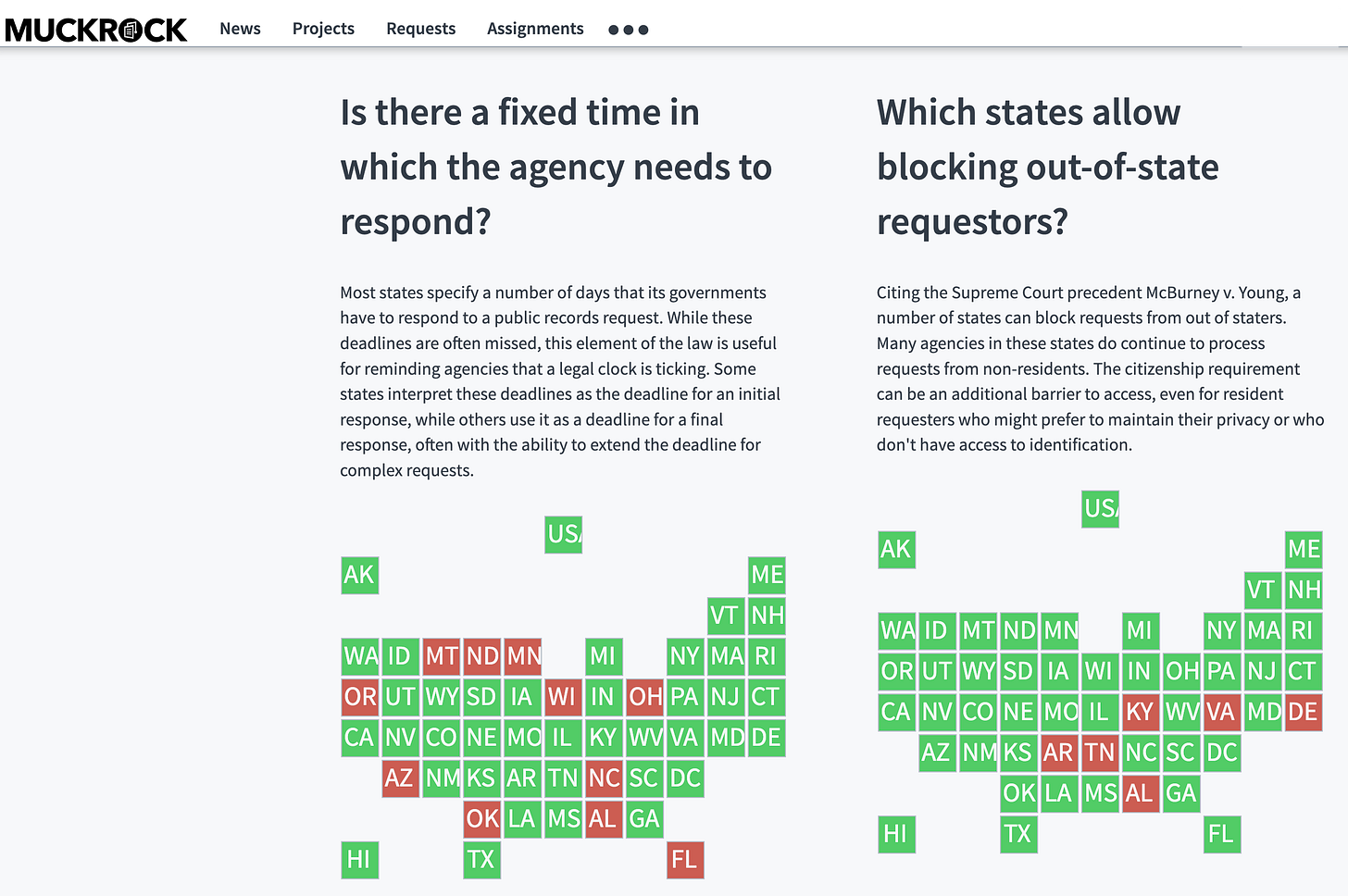

There are certain states where you must be a resident to get records. Virginia is one of them. Tennessee, Delaware, Arkansas, Alabama.

GC: Really?

Allan Blutstein: Yeah, it’s more of an inconvenience because you can always find a proxy requester to make the request for you. Tennessee is particularly stringent. They will ask for a driver’s license as proof of your residency if they have any reservations. Now, there are exceptions for reporters who have business or cover stories out of state. But I’ve had trouble making requests to the states that I mentioned. I’ll have to find a friend. Or there is an organization called Muck Rock that will help requesters find proxies. So I don’t know how effective the restriction really is.

GC: What do you think of those exceptions for reporters, being treated differently than the average citizen? Is that fair?

Allan Blutstein: The subject of fees has come up at the federal level. The National Archives has a federal FOIA advisory committee that I served on for one two-year term. The idea of changing the fee structure has come up. I think the most popular idea was just to have a flat fee — everyone should pay just a modest flat fee amount because I think employees don’t want to deal with all the fee issues that come up. What category are you in? Do you qualify for a fee waiver? So instead of fighting about all that, a flat fee for everyone might be more convenient. On the other hand, if one requester is asking for thousands of pages and another is asking for just a few, a flat fee doesn’t seem to be fair in that situation.

I’m probably an outlier on this issue. I don’t think there should be preferred fee categories. If you’re getting free research time as a reporter or another preferred fee category, I don’t know what prevents that individual from submitting lots of requests and requests that involve quite a bit of search time. I know there’s an argument that the records reporters obtain are for the public interest, that they’re doing good oversight work. I understand that, but it’s also contributing to backlog requests and delays. I don’t know if fees are really the root of the problem.

Others will argue that the $600 million budget the government spends to process requests is a drop in the bucket compared to what they’re spending and that it’s outweighed by the public benefit. I understand that, but at some point, that becomes real money. The number of requests filed every year keeps increasing. The Department of Justice just released the latest data for 2024, and the costs for processing requests were $601 million, as well as $55 million for litigation costs (see breakdown by agency below). The number of requests increased from about 1.2 million in FY 2023 to 1.5 million in FY 2024.

The response times are not getting better. It’s difficult work. Attracting people to this field is not easy, I imagine less so after these mass layoffs. But I don’t think I have an answer. And this advisory committee hasn’t come up with any recommendations yet, so I suppose that’s why there’s still status quo. Congress did try to incentivize agencies to improve their response times by cutting off their ability to collect fees if they were late. But I’m not sure that works. Agencies don’t get to keep the money that they’re charging. It all goes to the General Treasury for the most part. So agencies don’t really care about the money per se. They’re not motivated.

GC: So what is your recommendation?

Allan Blutstein: I’ll stick to my guns. I think there should be some sort of flat fee structure, maybe by the volume of records. And I would keep the waiver principle, get rid of the categories, the fee categories, but allow people to apply, ask for a waiver in the public interest. In other words, these records are not for private benefit. I’m not going to make money off of these records. They will shed light on an important government operation. And so in that situation, there would be no fees.

There are organizations that send out thousands and thousands of requests under the guise of being representatives of the news media because they have a website. They’re not traditional reporters, but they nevertheless qualify for preferred fee status. And you really want to avoid flooding the government with thousands and thousands of requests. I go back and forth on it. There are no limits on how many requests someone can file, but at some point it’s venturing into the vexatious territory. That’s a hard line to draw. So some states have provisions where you can cut off a requester for being vexatious, but they’re very controversial and I don’t see the federal government enacting anything along those lines.

GC: Thank you.

Nice how to. Thanks for helping citizen journalists. Democracy dies in the darkness!

Congratulations, Greg. I'm really pleased with the direction you and Matt are taking. Keep up the great work!